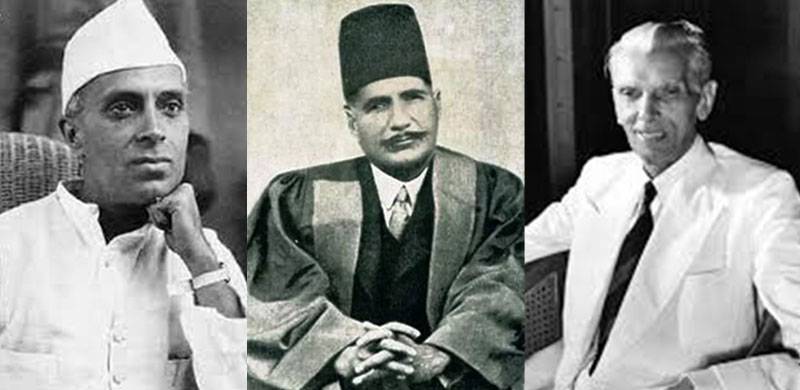

Tripurdaman Singh and Adeel Hussain, an Indian and a Pakistani historian, have co-authored the book, Nehru, the debates that defined India. This book contains rich primary source material on the debates that the first prime minister of India undertook with four stalwarts of his time, Iqbal, Jinnah, Patel and Mookerjee. With Patel he sparred over China and communism. His debate with Mookerjee was about the nature of the first amendment to the Indian constitution through which Nehru’s administration sought to curb the right to freedom of expression and speech. The debate with Iqbal was over theological questions and the debate with Jinnah was about Muslim political demands.

All five of these men were barristers called to the bar in England and Wales. Jinnah, Iqbal and Mookerjee were called to the bar at Lincoln’s Inn, Nehru at Inner Temple Inn and Patel at Middle Temple Inn. This makes the debates between them all the more interesting.

While the authors of this book say that these debates defined India, these debates equally defined Pakistan. Even the Mookerjee debate which speaks about the curbs on freedom of expression and speech is relevant because the clawbacks adopted by all three constitutions of Pakistan seem like a replica of the Indian constitution post-first amendment.

For most Pakistanis though the debates that Nehru entered into with Iqbal and Jinnah are relevant even today. They make for interesting reading because some of the issues discussed in these debates are issues Pakistanis are still grappling with. Of the two men – held in such high esteem by Pakistanis - Nehru seems to have had a special fondness for Iqbal and equal disdain for Jinnah. As the book reminds us Iqbal on his deathbed had told Nehru: “What is there in common between Jinnah and you? He is a politician, you are a patriot.”

Of course Iqbal and Nehru had much in common. Both were Cambridge educated barristers who were not enamoured by the practice of law, unlike Jinnah who was considered one of the finest barristers if not the top barrister in India. Iqbal and Nehru were both Kashmiris and of Brahmin stock even though Iqbal’s Sapru ancestors had converted to Islam. What seems to have ignited the Iqbal-Nehru public debate was an article that Iqbal wrote on the issue of Ahmadis (who he insisted on calling Qadianis – probably distinguishing them from the Lahori sub-sect).

In this, Iqbal endeavoured to explain his point of view vis a vis the much maligned sect in terms of the “threat” it posed to Islamic solidarity and the belief in finality of prophethood and described the whole Ahmadi movement a return to Magian culture. He further asked the British government to declare Ahmadis a separate community from Muslims. Nehru’s riposte came in three parts but it was somewhat strange that he should have responded at all. After all, as the authors point out, “it would not have escaped Nehru’s notice that only Ahmadiyya delegates stood by Jinnah’s proposals to bolster constitutional safeguards for Indian Muslims in the Nehru Report.”

Therefore, to Nehru, Iqbal’s blistering attack on Ahmadis must have been very surprising. Things did not fit neatly into the equation that Nehru had set up. The gist of Nehru’s argument was that the colonial state should not be brought into determining such a dispute. In this new equation, Jinnah and Nehru were on the one side, and Iqbal on the other i.e. secular minded politicians versus a religious poet-philosopher on the question of state’s interference into the personal religious domain.

Jinnah would go on to resist tremendous pressures from the orthodoxy to turn Ahmadis out of the Muslim League and even more ironically Nehru supported Majlis-e-Ahrar -- a rabidly sectarian and bigoted organisation – which essentially shared Iqbal’s views on Ahmadis. It was a strange and ironic twist that after having so valiantly defended the Ahmadis in 1935, Nehru should have turned to Majlis-e-Ahrar despite the ideological congruence that Ahrar had to Iqbal’s views. Both Nehru and Jinnah had been right that the state had no right to determine a person’s faith and relationship with the God, but political expediency makes people do strange things.

The first part of Nehru’s response dealt with the question of Islamic solidarity and how it affected the genuine development of nationalism. The second part of his response was a blistering attack on Aga Khan and Ismailis – something which catches the reader by surprise. It is full of sarcasm and seeks to portray Aga Khan as the lackey of British imperialism as well as being a bad Muslim exploiting his followers financially. The point however that Nehru makes is that if Ahmadis were disrupting the solidarity of Islam, Aga Khan and his followers with their heterodox beliefs should also have been considered heretical, because, according to Nehru, Ismailis believed that Aga Khan was divine.

The third part is where Nehru asks the orthodox of all religions to unite citing his encounter with anti-Sarda bill protests where conservative Muslims and Hindus chanted slogans side by side. The bill, which was passed as the Child Marriages Restraint Act 1929, fixed the minimum age of marriage for girls. Interestingly one of the bill’s chief proponents was none other than Mohammed Ali Jinnah himself, which makes Nehru’s later acerbic attacks on Jinnah all the more ironic.

It was Jinnah who bore the brunt of religious reaction repeatedly. It was Jinnah who faced the orthodox among Hindus and Muslims during the Khilafat and Non-cooperation movement. Nehru would later attack Jinnah as having become petty minded because of what to Nehru seemed religious posturing. He must have had a hard time fitting Jinnah into a box. One wonders what Nehru thought of Majlis-e-Ahrar when they called Jinnah Kafir-e-Azam or the great infidel.

To understand the Jinnah-Nehru dispute, one has to read the correspondence between them. The dispute between Jinnah and Nehru was always about how power sharing would happen between Hindus and Muslims in the post-Independence India. Nehru believed that religious identity had no place in politics while Jinnah had come to believe that Muslims as a minority needed specific safeguards in the post-India constitution, including guaranteed share in the government.

It is often overlooked that in 1937, the Muslim League and Congress fought the elections together with an understanding that they would form coalition governments. Both the Congress and Muslim League failed to make inroads into Punjab and Bengal but the Muslim League did win on Muslim seats in the UP, and Bombay. The Congress, which had won the overall majority, refused to fulfill its pledge to form a coalition government with the Muslim League, with Nehru almost arrogantly asking the League members to join the Congress first.

Nehru had a very nuanced – if not always balanced - opinion of Jinnah. In his book The Discovery of India, Nehru notes: “Mr. M. A. Jinnah himself was more advanced than most of his colleagues of the Moslem League. Indeed he stood head and shoulders above them and had therefore become the indispensable leader. From public platforms he confessed his great dissatisfaction with the opportunism, and sometimes even worse failings, of his colleagues. He knew well that a great part of the advanced, selfless, and courageous element among the Moslems had joined and worked with the Congress. And yet some destiny or course of events had thrown him among the very people for whom he had no respect. He was their leader but he could only keep them together by becoming himself a prisoner to their reactionary ideologies. Not that he was an unwilling prisoner, so far as the ideologies were concerned, for despite his external modernism, he belonged to an older generation which was hardly aware of modern political thought or development. ….He had left the Congress when the organization had taken a political leap forward. The gap had widened as the Congress developed an economic and mass outlook. But Mr. Jinnah seemed to have remained ideologically in that identical place where he stood a generation ago, or rather he had gone further back, for now he condemned both India's unity and democracy… It took him a long time to realize that what he had stood for throughout a fairly long life was nonsensical.”

And then this: “Mr. Jinnah was a different type. He was able, tenacious, and not open to the lure of office, which had been such a failing of so many others.”

To Nehru, Jinnah had left the Congress because the party had taken a step forward presumably of becoming a mass movement. Of course the irony here is that the Congress became a mass movement by fanning the same kind of religious reaction in both Hindus and Muslims that Nehru himself complained of and Jinnah’s break with the Congress came because of Jinnah’s utter distaste for that kind of politics. Here, again, there was common ground that Nehru could have built on but tragically some sort of self-righteousness prevented him from doing so. Those who have read Jinnah’s speeches in the legislature know that Jinnah was ahead of his times when considering issues of the day, and well aware of modern political thought and development.

In the Jinnah-Nehru exchange of 1938, we see these issues coming to fore. The great duel that the two stalwarts engage in revolves entirely around the question of representation. Jinnah wanted Nehru to deal with the Muslim League as the sole representative body of Muslims just as the Congress had done so in 1916 at Lucknow. Nehru, somewhat arrogantly, replied, “There are special Muslim organizations such as the Jamiat-ul-Ulema, the Proja Party, the Ahrars and others, which claim attention. Inevitably the more important the organization, the more the attention paid to it, but this importance does not come from outside recognition but from inherent strength. And the other organizations, even though they might be younger and smaller, cannot be ignored.”

This seemed to have cut deeply for Jinnah because he responded with, “Here I may add that in my opinion, as I have publicly stated so often, that unless the Congress recognizes the Muslim League on a footing of complete equality and is prepared as such to negotiate for a Hindu-Muslim settlement, we shall have to wait and depend upon our inherent strength which will ‘determine the measure of importance or distinction it possesses’.”

The tragedy was – as stated above - that Nehru was elevating bigoted sectarian organisations as examples of why the Muslim League could not be the sole representative body for Muslims. For all of Nehru’s complaints against the British about dividing and ruling India, here Nehru was dividing Muslims to rule them. A settlement in 1937-1938 was more than possible but for this. On the one hand Nehru stood for secular Indian nationalism, on the other he supported bigoted right-wing religious Islamist organisations. This was nothing new of course. The alliance between the Congress and the Islamist religious parties went back to the Khilafat Movement, where the Khilafatists had emerged as Gandhi’s greatest allies, and together they had set about isolating and alienating secular Muslim voices such as that of Jinnah.

While one understands that Gandhi, being a religious man himself, was likely to support religiously-inclined of other faiths, Nehru’s reliance on parties like the Jamiat-e-Ulema Hind and Majlis-e-Ahrar seems out of place with his secular ideology and nationalism.

Jinnah and Nehru both agreed on the idea of secular citizenship. The difference between them was one of representation for minorities. Surely a consociational solution would have in the longer run worked towards a fusion of Hindus and Muslims into a secular Indian identity but Nehru seemed to have been very impatient.

Eventually this debate was the curtain raiser for partition.

All five of these men were barristers called to the bar in England and Wales. Jinnah, Iqbal and Mookerjee were called to the bar at Lincoln’s Inn, Nehru at Inner Temple Inn and Patel at Middle Temple Inn. This makes the debates between them all the more interesting.

While the authors of this book say that these debates defined India, these debates equally defined Pakistan. Even the Mookerjee debate which speaks about the curbs on freedom of expression and speech is relevant because the clawbacks adopted by all three constitutions of Pakistan seem like a replica of the Indian constitution post-first amendment.

For most Pakistanis though the debates that Nehru entered into with Iqbal and Jinnah are relevant even today. They make for interesting reading because some of the issues discussed in these debates are issues Pakistanis are still grappling with. Of the two men – held in such high esteem by Pakistanis - Nehru seems to have had a special fondness for Iqbal and equal disdain for Jinnah. As the book reminds us Iqbal on his deathbed had told Nehru: “What is there in common between Jinnah and you? He is a politician, you are a patriot.”

Of course Iqbal and Nehru had much in common. Both were Cambridge educated barristers who were not enamoured by the practice of law, unlike Jinnah who was considered one of the finest barristers if not the top barrister in India. Iqbal and Nehru were both Kashmiris and of Brahmin stock even though Iqbal’s Sapru ancestors had converted to Islam. What seems to have ignited the Iqbal-Nehru public debate was an article that Iqbal wrote on the issue of Ahmadis (who he insisted on calling Qadianis – probably distinguishing them from the Lahori sub-sect).

In this, Iqbal endeavoured to explain his point of view vis a vis the much maligned sect in terms of the “threat” it posed to Islamic solidarity and the belief in finality of prophethood and described the whole Ahmadi movement a return to Magian culture. He further asked the British government to declare Ahmadis a separate community from Muslims. Nehru’s riposte came in three parts but it was somewhat strange that he should have responded at all. After all, as the authors point out, “it would not have escaped Nehru’s notice that only Ahmadiyya delegates stood by Jinnah’s proposals to bolster constitutional safeguards for Indian Muslims in the Nehru Report.”

Therefore, to Nehru, Iqbal’s blistering attack on Ahmadis must have been very surprising. Things did not fit neatly into the equation that Nehru had set up. The gist of Nehru’s argument was that the colonial state should not be brought into determining such a dispute. In this new equation, Jinnah and Nehru were on the one side, and Iqbal on the other i.e. secular minded politicians versus a religious poet-philosopher on the question of state’s interference into the personal religious domain.

Jinnah and Nehru were on the one side, and Iqbal on the other i.e. secular minded politicians versus a religious poet-philosopher on the question of state’s interference into the personal religious domain.

Jinnah would go on to resist tremendous pressures from the orthodoxy to turn Ahmadis out of the Muslim League and even more ironically Nehru supported Majlis-e-Ahrar -- a rabidly sectarian and bigoted organisation – which essentially shared Iqbal’s views on Ahmadis. It was a strange and ironic twist that after having so valiantly defended the Ahmadis in 1935, Nehru should have turned to Majlis-e-Ahrar despite the ideological congruence that Ahrar had to Iqbal’s views. Both Nehru and Jinnah had been right that the state had no right to determine a person’s faith and relationship with the God, but political expediency makes people do strange things.

The first part of Nehru’s response dealt with the question of Islamic solidarity and how it affected the genuine development of nationalism. The second part of his response was a blistering attack on Aga Khan and Ismailis – something which catches the reader by surprise. It is full of sarcasm and seeks to portray Aga Khan as the lackey of British imperialism as well as being a bad Muslim exploiting his followers financially. The point however that Nehru makes is that if Ahmadis were disrupting the solidarity of Islam, Aga Khan and his followers with their heterodox beliefs should also have been considered heretical, because, according to Nehru, Ismailis believed that Aga Khan was divine.

The third part is where Nehru asks the orthodox of all religions to unite citing his encounter with anti-Sarda bill protests where conservative Muslims and Hindus chanted slogans side by side. The bill, which was passed as the Child Marriages Restraint Act 1929, fixed the minimum age of marriage for girls. Interestingly one of the bill’s chief proponents was none other than Mohammed Ali Jinnah himself, which makes Nehru’s later acerbic attacks on Jinnah all the more ironic.

It was Jinnah who bore the brunt of religious reaction repeatedly. It was Jinnah who faced the orthodox among Hindus and Muslims during the Khilafat and Non-cooperation movement. Nehru would later attack Jinnah as having become petty minded because of what to Nehru seemed religious posturing. He must have had a hard time fitting Jinnah into a box. One wonders what Nehru thought of Majlis-e-Ahrar when they called Jinnah Kafir-e-Azam or the great infidel.

To understand the Jinnah-Nehru dispute, one has to read the correspondence between them. The dispute between Jinnah and Nehru was always about how power sharing would happen between Hindus and Muslims in the post-Independence India. Nehru believed that religious identity had no place in politics while Jinnah had come to believe that Muslims as a minority needed specific safeguards in the post-India constitution, including guaranteed share in the government.

It is often overlooked that in 1937, the Muslim League and Congress fought the elections together with an understanding that they would form coalition governments. Both the Congress and Muslim League failed to make inroads into Punjab and Bengal but the Muslim League did win on Muslim seats in the UP, and Bombay. The Congress, which had won the overall majority, refused to fulfill its pledge to form a coalition government with the Muslim League, with Nehru almost arrogantly asking the League members to join the Congress first.

Nehru had a very nuanced – if not always balanced - opinion of Jinnah. In his book The Discovery of India, Nehru notes: “Mr. M. A. Jinnah himself was more advanced than most of his colleagues of the Moslem League. Indeed he stood head and shoulders above them and had therefore become the indispensable leader. From public platforms he confessed his great dissatisfaction with the opportunism, and sometimes even worse failings, of his colleagues. He knew well that a great part of the advanced, selfless, and courageous element among the Moslems had joined and worked with the Congress. And yet some destiny or course of events had thrown him among the very people for whom he had no respect. He was their leader but he could only keep them together by becoming himself a prisoner to their reactionary ideologies. Not that he was an unwilling prisoner, so far as the ideologies were concerned, for despite his external modernism, he belonged to an older generation which was hardly aware of modern political thought or development. ….He had left the Congress when the organization had taken a political leap forward. The gap had widened as the Congress developed an economic and mass outlook. But Mr. Jinnah seemed to have remained ideologically in that identical place where he stood a generation ago, or rather he had gone further back, for now he condemned both India's unity and democracy… It took him a long time to realize that what he had stood for throughout a fairly long life was nonsensical.”

Those who have read Jinnah’s speeches in the legislature know that Jinnah was ahead of his times when considering issues of the day, and well aware of modern political thought and development.

And then this: “Mr. Jinnah was a different type. He was able, tenacious, and not open to the lure of office, which had been such a failing of so many others.”

To Nehru, Jinnah had left the Congress because the party had taken a step forward presumably of becoming a mass movement. Of course the irony here is that the Congress became a mass movement by fanning the same kind of religious reaction in both Hindus and Muslims that Nehru himself complained of and Jinnah’s break with the Congress came because of Jinnah’s utter distaste for that kind of politics. Here, again, there was common ground that Nehru could have built on but tragically some sort of self-righteousness prevented him from doing so. Those who have read Jinnah’s speeches in the legislature know that Jinnah was ahead of his times when considering issues of the day, and well aware of modern political thought and development.

In the Jinnah-Nehru exchange of 1938, we see these issues coming to fore. The great duel that the two stalwarts engage in revolves entirely around the question of representation. Jinnah wanted Nehru to deal with the Muslim League as the sole representative body of Muslims just as the Congress had done so in 1916 at Lucknow. Nehru, somewhat arrogantly, replied, “There are special Muslim organizations such as the Jamiat-ul-Ulema, the Proja Party, the Ahrars and others, which claim attention. Inevitably the more important the organization, the more the attention paid to it, but this importance does not come from outside recognition but from inherent strength. And the other organizations, even though they might be younger and smaller, cannot be ignored.”

This seemed to have cut deeply for Jinnah because he responded with, “Here I may add that in my opinion, as I have publicly stated so often, that unless the Congress recognizes the Muslim League on a footing of complete equality and is prepared as such to negotiate for a Hindu-Muslim settlement, we shall have to wait and depend upon our inherent strength which will ‘determine the measure of importance or distinction it possesses’.”

The tragedy was – as stated above - that Nehru was elevating bigoted sectarian organisations as examples of why the Muslim League could not be the sole representative body for Muslims. For all of Nehru’s complaints against the British about dividing and ruling India, here Nehru was dividing Muslims to rule them. A settlement in 1937-1938 was more than possible but for this. On the one hand Nehru stood for secular Indian nationalism, on the other he supported bigoted right-wing religious Islamist organisations. This was nothing new of course. The alliance between the Congress and the Islamist religious parties went back to the Khilafat Movement, where the Khilafatists had emerged as Gandhi’s greatest allies, and together they had set about isolating and alienating secular Muslim voices such as that of Jinnah.

While one understands that Gandhi, being a religious man himself, was likely to support religiously-inclined of other faiths, Nehru’s reliance on parties like the Jamiat-e-Ulema Hind and Majlis-e-Ahrar seems out of place with his secular ideology and nationalism.

Jinnah and Nehru both agreed on the idea of secular citizenship. The difference between them was one of representation for minorities. Surely a consociational solution would have in the longer run worked towards a fusion of Hindus and Muslims into a secular Indian identity but Nehru seemed to have been very impatient.

Eventually this debate was the curtain raiser for partition.