Views and convictions centered on menstruation differ across societies, but remain an unthinkable topic to talk about in the Global South. In some areas, the women going through the flow are victimised, thanks to the degenerating attitude that revolves around menstruation. In various others, the topic is impossible to discuss because it is wrapped around embarrassment, shame and disgrace. However, the fact remains the same for all those who go through this very normal and natural biological phenomenon – it is a battle, indeed.

Farah Ahamed dared to chronicle this feat of breaking the stigma associated with the cycle. When she was in Uganda, she realised the importance of menstrual hygiene management. She established an informal initiative called Panties with Purpose, the objective of which was to promote menstrual health and raise awareness about the harmful effects on girls in Kenya – such as missing nearly sixty days of school per year because of a lack of access to menstrual products, that damaged their chances for academic success and compromised their health and well-being.

So, what started as a mere discussion with family and friends soon spread farther, and there were strangers writing to tell her that they were hosting parties and asking their guests to contribute to the initiative. Organisations reached out to Ahamed, stating that they were formally including Panties with Purpose in their corporate social responsibility budget. The initiative has reached far and wide, through schools, colleges, organisations, hospitals, marketplaces, orphanages, prisons, and shelters for the homeless, that engage in fund-raising concerts, sponsored health education, skills-training workshops, developing environmentally-friendly sanitary pad options using local materials such as sisal, and removal of the tampon tax.

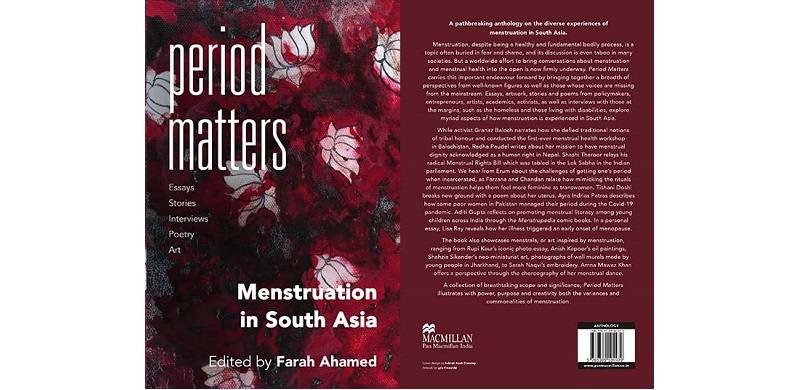

Ahamed’s latest and exemplary contribution to the cause is editing the book Period Matters, which includes real texts and art forms, worked upon by many celebrities, transgender people, artists, activists, the homeless, and women in prisons, relaying their menstrual experiences, memories, stories, and suffering. This stellar collection of essays, artwork, interviews, and stories was a result of the battles they fought primarily because some perceptions rendered women unclean and their bodies dirty; as though not sacred enough to befit everyday chores. These beliefs reduce women into recluses and sometimes force them to live in isolation.

All of them emerge from diverse cultural backgrounds birthing various forms of arts, including poetry, paintings, and dance (a QR code on page 44 can be scanned to watch the performance – Raqs-e-Mahwari), which shapes the exploration of the subject and the participants’ creative expressions that are innately developed out of it.

The text covers a breadth of perspectives. For instance, the essay by Tashi Zangmo wanders through nunneries in Bhutan, recounting her ongoing efforts with the Buddhist Nuns Foundation to revolutionise menstrual health in the nunneries. Activist Granaz Baloch explains how she challenged traditional notions of tribal honour and conducted the first-ever menstrual health workshop in Balochistan, Pakistan. Radha Paudel pens down her mission to have menstrual dignity acknowledged as a human right in Nepal. Shashi Tharoor, in his My Menstrual Rights Bill, discusses the fundamental right which was tabled in the Lok Sabha in the Indian parliament. Meera Tiwari’s research on Uttar Pradesh and Bihar employs a ‘menstrual dignity framework’ to evaluate data collected from street theatre performances. Radhika Radhakrishnan puts forward the case for period leave in the workplace in Right to Bleed at the Workplace. Shashi Deshpande’s Menstrual Matters openly narrates her own story of menstruation. We hear about the challenges of getting one’s period when incarcerated in Pakistan from Erum. Farzana and Chandan relate how mimicking the rituals of menstruation helps them to feel more feminine as transwomen, and Javed, a transman, shares his trauma of dysphoria. In her poems, Victoria Patrick imagines the hardships of the women menstruating during the traumatic days of Partition and the homeless women who have to cope with menstruation without the basic amenities, titled Anguish of the Unveiled. Srilekha Chakraborty offers her insights into working with India’s indigenous Adivasi community, in Hormo-baha: Flower of the Body. Tishani Doshi shares two poems, Advice for Pliny the Elder, about her uterus, and Big Daddy of Mansplainers, a note to mansplainers.

Apart from writing, menstrala (art inspired by menstruation) plays a powerful part in this anthology: Rupi Kaur’s photo essay, reproductions of Anish Kapoor’s oil paintings, Lyla FreeChild’s menstrual blood art and Shahzia Sikander’s neo-miniaturist art, photographs of the wall murals made by young people in Jharkhand and Sarah Naqvi’s delicate needlework. And with graceful movements, Amna Mawaz Khan offers a perspective on menstruation through the choreography of her menstrual dance. Each artist, using his or her preferred medium, has shone a light on different aspects of menstruation.

All of them are quite diverse in expression, yet coalesce in the larger picture. The author has gracefully covered it all with a wider lens inclusive of class, religions, gender, and disabilities. Every viewpoint has empathy and connection that all menstruators experience.

Farah Ahamed dared to chronicle this feat of breaking the stigma associated with the cycle. When she was in Uganda, she realised the importance of menstrual hygiene management. She established an informal initiative called Panties with Purpose, the objective of which was to promote menstrual health and raise awareness about the harmful effects on girls in Kenya – such as missing nearly sixty days of school per year because of a lack of access to menstrual products, that damaged their chances for academic success and compromised their health and well-being.

So, what started as a mere discussion with family and friends soon spread farther, and there were strangers writing to tell her that they were hosting parties and asking their guests to contribute to the initiative. Organisations reached out to Ahamed, stating that they were formally including Panties with Purpose in their corporate social responsibility budget. The initiative has reached far and wide, through schools, colleges, organisations, hospitals, marketplaces, orphanages, prisons, and shelters for the homeless, that engage in fund-raising concerts, sponsored health education, skills-training workshops, developing environmentally-friendly sanitary pad options using local materials such as sisal, and removal of the tampon tax.

Ahamed’s latest and exemplary contribution to the cause is editing the book Period Matters, which includes real texts and art forms, worked upon by many celebrities, transgender people, artists, activists, the homeless, and women in prisons, relaying their menstrual experiences, memories, stories, and suffering. This stellar collection of essays, artwork, interviews, and stories was a result of the battles they fought primarily because some perceptions rendered women unclean and their bodies dirty; as though not sacred enough to befit everyday chores. These beliefs reduce women into recluses and sometimes force them to live in isolation.

All of them emerge from diverse cultural backgrounds birthing various forms of arts, including poetry, paintings, and dance (a QR code on page 44 can be scanned to watch the performance – Raqs-e-Mahwari), which shapes the exploration of the subject and the participants’ creative expressions that are innately developed out of it.

The text covers a breadth of perspectives. For instance, the essay by Tashi Zangmo wanders through nunneries in Bhutan, recounting her ongoing efforts with the Buddhist Nuns Foundation to revolutionise menstrual health in the nunneries. Activist Granaz Baloch explains how she challenged traditional notions of tribal honour and conducted the first-ever menstrual health workshop in Balochistan, Pakistan. Radha Paudel pens down her mission to have menstrual dignity acknowledged as a human right in Nepal. Shashi Tharoor, in his My Menstrual Rights Bill, discusses the fundamental right which was tabled in the Lok Sabha in the Indian parliament. Meera Tiwari’s research on Uttar Pradesh and Bihar employs a ‘menstrual dignity framework’ to evaluate data collected from street theatre performances. Radhika Radhakrishnan puts forward the case for period leave in the workplace in Right to Bleed at the Workplace. Shashi Deshpande’s Menstrual Matters openly narrates her own story of menstruation. We hear about the challenges of getting one’s period when incarcerated in Pakistan from Erum. Farzana and Chandan relate how mimicking the rituals of menstruation helps them to feel more feminine as transwomen, and Javed, a transman, shares his trauma of dysphoria. In her poems, Victoria Patrick imagines the hardships of the women menstruating during the traumatic days of Partition and the homeless women who have to cope with menstruation without the basic amenities, titled Anguish of the Unveiled. Srilekha Chakraborty offers her insights into working with India’s indigenous Adivasi community, in Hormo-baha: Flower of the Body. Tishani Doshi shares two poems, Advice for Pliny the Elder, about her uterus, and Big Daddy of Mansplainers, a note to mansplainers.

Apart from writing, menstrala (art inspired by menstruation) plays a powerful part in this anthology: Rupi Kaur’s photo essay, reproductions of Anish Kapoor’s oil paintings, Lyla FreeChild’s menstrual blood art and Shahzia Sikander’s neo-miniaturist art, photographs of the wall murals made by young people in Jharkhand and Sarah Naqvi’s delicate needlework. And with graceful movements, Amna Mawaz Khan offers a perspective on menstruation through the choreography of her menstrual dance. Each artist, using his or her preferred medium, has shone a light on different aspects of menstruation.

All of them are quite diverse in expression, yet coalesce in the larger picture. The author has gracefully covered it all with a wider lens inclusive of class, religions, gender, and disabilities. Every viewpoint has empathy and connection that all menstruators experience.