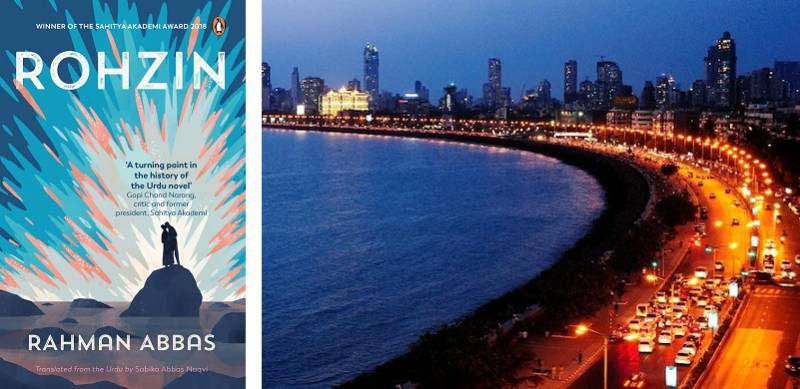

The novel Rohzin, or The Melancholy of the Soul, by Rahman Abbas, features Mumbai (previously Bombay) as the protagonist where its geography, history and folklore trickle into the characters’ lives and imaginings. The book, comprising eight chapters, is a true feast for the mind and soul. In Urdu, Abbas attempts to echo ‘Rohzin’ to signify the depths of people’s hurt. Here is a love story, marked by desire, belonging, denial and identity with a peripheral backdrop of the city of Mumbai. Critics in the Global South think of Rohzin as a literary landmark in Urdu literature. As modern as the novel is in terms of questioning present-day lifestyles without much discourse on social orders and conformities, it interrogates the cultural curators of Karachi too. The book earned Abbas the Sahitya Academi Award, India’s most prestigious literary award, in 2018. A German translation was published in 2018, and an English one has been recently released by Penguin, India, translated by Sabika Abbas Naqvi from Urdu.

The story opens with Asrar, who moves from his coastal village of Mabadmorpho in the Konkan, to Mumbai, in search of work. He stays at a “jamat ki kholi,” his village’s communal housing for migrants to the megacity. Asrar explores Mumbai with other residents as he lives with young men in abject poverty. Hina on the other hand comes from a relatively well-to-do, prosperous family, stained by more of a European issue of divorced parents between whom she feels stuck, while she ponders her career path and educational decisions. The two fall in love and become a couple. Quite apparently, their bond bridges social discrepancies. Both the protagonists are Muslims. Islam spells the cultural proportions of one’s identity, but not for Hina and Asrar. Their daily lives are guided by curiosity rather than some Islamic code. Lust and love seem to be the dominant forces in the story, especially the Bollywood-style meeting between Hina and Asrar that sparks immediate adoration, craving, and passion; a school teacher finds solace in her student’s embrace; a blunt businessman finds peace and purpose in a Satanic cult; his separated wife engenders consolation in spirituality.

Rahman Abbas further cements this assertion, “I wanted to write a novel about Mumbai. This was not difficult to achieve as Mumbai is my love and experience. But the theme that was then running in my head was a bit complex and challenging. I wanted to write it in a very sublime way so that it won't create uncalled-for glitches as I had faced a decade-long court appearance after obscenity charges on my first novel, earlier on. Hence, I played with many surrealistic elements to create a milieu of unreal and question infidelity, love, and betrayal in today’s life, our perception about these emotions at the universal level, while re-telling the story of the fall of Iblis and the birth of Adam, which is also depicted in the Semitic scriptures. To merge that into the narrative, I took cues from the history of modern Satanism. However, all of this was, in fact, to hide myself as the narrator, and luckily that seems to have worked.”

Although south Mumbai seems to be the epicentre of the story, the novel also unfolds across the region covering the original seven islands of the city, which the British linked through land reclamation. The landmarks such as Marine Drive and the Taj Hotel stand prominently, along with Nagpada, Pydhonie, Manish Market and the Mumba Devi Temple. The author ensures to soak these localities with the ordinary and the extraordinary, which allow his probes of sex and relationships to skew toward the pleasant and fascinating, perhaps even a tad bit mystifying.

Rahman sketches ornate characters for the male protagonists, while he traverses through the women mostly in relation to the men. The story is also peppered with several djinns, deities and spirits who interact with the humans and the city. With the satanic cult, Rahman builds a frightening aura. A vendor in Chor Bazaar holds a manuscript that his father considered world-shaking in case it becomes commonplace – the world will “submerge in blood.” At Haji Ali Dargah, Asrar engages in a thoughtful conversation with the sea where they settle that sex and love are independent of each other. At a luxury hotel, Rahman prompts that the window a character looks out from is the spot from where a terrorist threw a hand-grenade at the Gateway of India during the 26/11 attacks. Notable and epochal happenings such as the riots after the Babri Masjid demolition in 1992, the Zaveri Market bomb blast, and the 2005 flood transect with the characters. The city almost acts like a “battleground for the unstoppable rainwater and the roaring sea.” As if reiterating Karachi’s condition, Mumbai’s notorious rain frequently hits the story, feeding on the forthcoming disaster.

The story is indulges in some well-versed poetry too. The poem on page 178 is by Utsavi Jha, while the couplet on page 20 is by the Urdu poet Akhlaq Mohammed Khan ‘Shahryar’ (1936–2012). Couplets by the Urdu poet Rajinder Manchanda Bani (1932–1981) have also been used in the novel. The original chapter titles are also said to be derived from a ghazal by Rajinder Manchanda Bani.

The novel’s first line forecasts the conclusion, but Abbas slithers through various storylines, characters and climaxes to keep the narrative unyielding. It forces us to wonder if and how Hina and Asrar will converge, what the cult will let loose, and what role the groundbreaking book will play. The author does not explore issues around infidelity, or consent despite dishonest partners and age-gaped relationships. But it is a clearly heartfelt love letter to the Urdu language.

At the tail end, a character reads from a book to explain the novel’s title: “Copulation is an easy cure of Rohzin — the soul’s melancholy[…] If a child witnessed the sexual indulgences of his or her parents or one of them, it caused huzn or melancholy in the child[…] The tried, tested and easy cure to this disease was the ecstasy of lovemaking.”

Needless to say, Naqvi has done a stellar job of translating the novel in an attempt to transcend the linguistic boundaries, providing a clear balance to the poetry and prose with equal measure.

The story opens with Asrar, who moves from his coastal village of Mabadmorpho in the Konkan, to Mumbai, in search of work. He stays at a “jamat ki kholi,” his village’s communal housing for migrants to the megacity. Asrar explores Mumbai with other residents as he lives with young men in abject poverty. Hina on the other hand comes from a relatively well-to-do, prosperous family, stained by more of a European issue of divorced parents between whom she feels stuck, while she ponders her career path and educational decisions. The two fall in love and become a couple. Quite apparently, their bond bridges social discrepancies. Both the protagonists are Muslims. Islam spells the cultural proportions of one’s identity, but not for Hina and Asrar. Their daily lives are guided by curiosity rather than some Islamic code. Lust and love seem to be the dominant forces in the story, especially the Bollywood-style meeting between Hina and Asrar that sparks immediate adoration, craving, and passion; a school teacher finds solace in her student’s embrace; a blunt businessman finds peace and purpose in a Satanic cult; his separated wife engenders consolation in spirituality.

Rahman Abbas further cements this assertion, “I wanted to write a novel about Mumbai. This was not difficult to achieve as Mumbai is my love and experience. But the theme that was then running in my head was a bit complex and challenging. I wanted to write it in a very sublime way so that it won't create uncalled-for glitches as I had faced a decade-long court appearance after obscenity charges on my first novel, earlier on. Hence, I played with many surrealistic elements to create a milieu of unreal and question infidelity, love, and betrayal in today’s life, our perception about these emotions at the universal level, while re-telling the story of the fall of Iblis and the birth of Adam, which is also depicted in the Semitic scriptures. To merge that into the narrative, I took cues from the history of modern Satanism. However, all of this was, in fact, to hide myself as the narrator, and luckily that seems to have worked.”

The story is peppered with several djinns, deities and spirits who interact with the humans and the city. With the satanic cult, Rahman builds a frightening aura

Although south Mumbai seems to be the epicentre of the story, the novel also unfolds across the region covering the original seven islands of the city, which the British linked through land reclamation. The landmarks such as Marine Drive and the Taj Hotel stand prominently, along with Nagpada, Pydhonie, Manish Market and the Mumba Devi Temple. The author ensures to soak these localities with the ordinary and the extraordinary, which allow his probes of sex and relationships to skew toward the pleasant and fascinating, perhaps even a tad bit mystifying.

Rahman sketches ornate characters for the male protagonists, while he traverses through the women mostly in relation to the men. The story is also peppered with several djinns, deities and spirits who interact with the humans and the city. With the satanic cult, Rahman builds a frightening aura. A vendor in Chor Bazaar holds a manuscript that his father considered world-shaking in case it becomes commonplace – the world will “submerge in blood.” At Haji Ali Dargah, Asrar engages in a thoughtful conversation with the sea where they settle that sex and love are independent of each other. At a luxury hotel, Rahman prompts that the window a character looks out from is the spot from where a terrorist threw a hand-grenade at the Gateway of India during the 26/11 attacks. Notable and epochal happenings such as the riots after the Babri Masjid demolition in 1992, the Zaveri Market bomb blast, and the 2005 flood transect with the characters. The city almost acts like a “battleground for the unstoppable rainwater and the roaring sea.” As if reiterating Karachi’s condition, Mumbai’s notorious rain frequently hits the story, feeding on the forthcoming disaster.

The story is indulges in some well-versed poetry too. The poem on page 178 is by Utsavi Jha, while the couplet on page 20 is by the Urdu poet Akhlaq Mohammed Khan ‘Shahryar’ (1936–2012). Couplets by the Urdu poet Rajinder Manchanda Bani (1932–1981) have also been used in the novel. The original chapter titles are also said to be derived from a ghazal by Rajinder Manchanda Bani.

The novel’s first line forecasts the conclusion, but Abbas slithers through various storylines, characters and climaxes to keep the narrative unyielding. It forces us to wonder if and how Hina and Asrar will converge, what the cult will let loose, and what role the groundbreaking book will play. The author does not explore issues around infidelity, or consent despite dishonest partners and age-gaped relationships. But it is a clearly heartfelt love letter to the Urdu language.

At the tail end, a character reads from a book to explain the novel’s title: “Copulation is an easy cure of Rohzin — the soul’s melancholy[…] If a child witnessed the sexual indulgences of his or her parents or one of them, it caused huzn or melancholy in the child[…] The tried, tested and easy cure to this disease was the ecstasy of lovemaking.”

Needless to say, Naqvi has done a stellar job of translating the novel in an attempt to transcend the linguistic boundaries, providing a clear balance to the poetry and prose with equal measure.