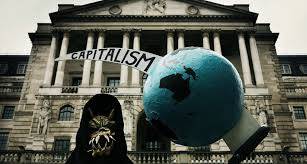

What might a concerned and intelligent society or polity do to counter these trends? Over the short term, the answer is not very much. Over the long term, as Marx and other political economists discovered and, indeed, trenchantly pointed out, capitalism perversely creates the very problems that also undermine it. Hence, both problems and solutions are part of the same process of capitalist growth and distribution of rewards. In that regard, first, it is now clear that capitalism has aggravated the problem of inequality generating new and more severe fissures and fault-lines in society (Piketty 2020). The wringing of hands will not do; large-scale State intervention will be needed. Concerted action is needed to break up all large corporations and deal with monopolization and experiment with new structures in production and distribution.

Second, capitalism has created huge negative externalities whereby profit-maximizers in their pursuit of profit have gone on to damage both the physical and non-physical environment for which all societies will have to pick up the bill for decades to come. An internationally agreed tax to pay for the restoration of the global environment is an urgent and unavoidable necessity.

Third, because of market failures compounded by the failure of States to correct them, has led to the systemic and gross under-provision of public goods, such as health, education and affordable housing over much of the world. Indeed, in response, the neoliberal version of capitalism, by weakening the capacity of the State to intervene, has made these problems well nigh insoluble. In this context, as the experience of the UK shows, with a pliant media in tow, society appears to have decided that these problems are either unimportant or do not exist.

Furthermore, who can doubt that running down the State has intensified the alienation that many in society currently feel from society itself. Alienation and its wider costs for society can never be tackled if public services are not properly funded. Today, the media are saturated with debates whether these services can be ‘afforded’.

The underlying issue in Western capitalist societies since their access to information became dominated by the social media is that reality has been pushed into the background and ‘reality’ is whatever is doing the rounds on social media in which individual agency has been fetishized to the point of self-indulgence. Traditional media, such as newspapers, magazines, TV and radio, itself with a pronounced right wing slant, have to battle it out with non-traditional media to get the attention of the populace but they have all lost ground rapidly and their long-term survival is hardly assured.

A recent study found that on Twitter, falsehoods dominate by every metric, reaching more people than does accurate, well-researched information (Sophia Rosenfeld 2019). If you add to falsehoods on the social media a constant barrage of right wing propaganda in the traditional media which generally denigrates collective action, the political process stands fundamentally compromised. To claim that the electoral process in the West produces genuinely democratic outcomes or that it produces deserving winners in the ‘market place of ideas’ is to believe a complete travesty.

Taking the UK as an example, this dysfunction has assisted the political process in avoiding having to confront its chronic long term challenges. Moreover, the obsession with pointless argument and trivia in the traditional media, such as culture wars, allows the UK government to keep attention focused on public debt as if it was a life and death matter, effectively ignoring or avoiding real crises in the grossly inadequate public services and the acute absence of fulfilling, well-rewarded jobs in the economy. Indeed, the laudable goal of promoting social cohesion by investing in the public sphere barely figures in any discussion in the UK media. This is a recipe not just for economic and social stagnation but for regression in the face of long-term challenges, such as the shift of the global economic centre of gravity to East Asia, and of the looming catastrophe of global warming.

There are of course some stray signs to the contrary outside the UK. In the US, the new administration is planning to spend massive sums of money to prevent mass unemployment and to invest in its run-down infrastructure. It is thereby outflanking the opportunism of right wing populism. Remarkably, in the country that invented neoliberalism, the size of the budget deficit no longer appears to be determining how much the US Administration is going to spend; the danger of mass unemployment does. Amazingly, even the IMF, the patron saint of neoliberalism, agrees. This is because fiscal rectitude has failed so visibly since the financial crisis that it has undermined not just faith in the State but now in capitalism itself. None other than the CEO of J P Morgan fears for the long term future of American capitalism and society.

In the UK, that realization has not yet dawned, given the nature of the media, and the mediocre intellectual discourse that dominates political discussion in the country. The UK seems to be blissfully unaware that QE (Quantitative Easing), first used by Japan in the 1990s, is common practice across the world with around $ 20 trillion of new money having been introduced into the global economy since 2008 to save it from collapse. The UK looks upon such developments with childish disdain.

In the UK, the ghosts of Hayek and Friedman are never too far from the surface even when the experience of real people ever comes up for discussion in the media. It is the pathological fear of public indebtedness that stalks the nooks and crannies of the country in the guise of responsible governance. It has effectively shut down all sensible discussion of the country’s problems and its future, although for most people the size of the public debt followed by unending austerity has failed to amount to a credible political narrative in the country. It is an obsession primarily of the UK ruling elite that has been elevated to the level of a quasi-religious creed.

Here, it should be emphasized that hardly any Western society or government has managed to cope well with the Covid 19 pandemic, partly because of a lack of preparation and partly because of an inability to decide that the pandemic and saving lives had to take priority over the economy. Against this, autocratic East Asia and quasi-democratic South-East Asia have succeeded in keeping both deaths from the virus and its associated economic dislocation under control.

Yet, these countries have few admirers in either the UK or in the wider Western world. On this basis, only an incorrigible optimist would believe that any Western government or society will be able to meet the daunting challenges of growing inequality or of a weakened social contract as public services wither, and, above all, of devastating global warming that may come sooner than most people expect. The problems facing the world are man-made; hence, within a radically different political and value system they are surely capable of solution (Will Hutton 2015).

As to the future of neoliberal capitalism, there is little doubt that like everything else that has come before, it, too, will eventually fade into history. In the past, capitalism was able to re-invent itself, for example in the 1930s, with Keynesian pump-priming and prevented mass unemployment, and after World War II with the creation of the welfare State, because the ruling elites were willing to do so as they feared revolution. In the UK, a torn social fabric needs a new social contract.

Above all else, a modern version of the Enlightenment is needed to create a gentler, more empathetic society in the developed countries in which the weak, such as the unemployed, migrants and refugees, are not demonized for the sake of fickle political advantage. For there to be social and political stability and a sense of hope in capitalist societies a different, much more humane, polity inspired by social justice will, sooner or later, have to be fashioned. To this end, education and an intelligent social media will have to create a climate of opinion so that politics is not left to the mercy of corporate interests, to the purveyors of outlandish conspiracy theories and in the hands of incompetent politicians.

Between 400 and 700 years ago the people of Easter Island (now a part of Chile) were talented canoeists and travelled far and wide over the South Pacific, collecting massive stone slabs that they then carved into human-like figures, presumably for worship. They discovered that in their zeal to travel and transport these slabs home they had succeeded in cutting down all the trees to make the canoes. Legend has it that their civilization collapsed within a few years leaving the massive stone figures that they worshipped as lonely sentinels of their past. It is a lesson that all capitalist societies need to heed if they are to meet the daunting challenges facing them.

Second, capitalism has created huge negative externalities whereby profit-maximizers in their pursuit of profit have gone on to damage both the physical and non-physical environment for which all societies will have to pick up the bill for decades to come. An internationally agreed tax to pay for the restoration of the global environment is an urgent and unavoidable necessity.

Third, because of market failures compounded by the failure of States to correct them, has led to the systemic and gross under-provision of public goods, such as health, education and affordable housing over much of the world. Indeed, in response, the neoliberal version of capitalism, by weakening the capacity of the State to intervene, has made these problems well nigh insoluble. In this context, as the experience of the UK shows, with a pliant media in tow, society appears to have decided that these problems are either unimportant or do not exist.

Furthermore, who can doubt that running down the State has intensified the alienation that many in society currently feel from society itself. Alienation and its wider costs for society can never be tackled if public services are not properly funded. Today, the media are saturated with debates whether these services can be ‘afforded’.

The underlying issue in Western capitalist societies since their access to information became dominated by the social media is that reality has been pushed into the background and ‘reality’ is whatever is doing the rounds on social media in which individual agency has been fetishized to the point of self-indulgence. Traditional media, such as newspapers, magazines, TV and radio, itself with a pronounced right wing slant, have to battle it out with non-traditional media to get the attention of the populace but they have all lost ground rapidly and their long-term survival is hardly assured.

A recent study found that on Twitter, falsehoods dominate by every metric, reaching more people than does accurate, well-researched information (Sophia Rosenfeld 2019). If you add to falsehoods on the social media a constant barrage of right wing propaganda in the traditional media which generally denigrates collective action, the political process stands fundamentally compromised. To claim that the electoral process in the West produces genuinely democratic outcomes or that it produces deserving winners in the ‘market place of ideas’ is to believe a complete travesty.

Taking the UK as an example, this dysfunction has assisted the political process in avoiding having to confront its chronic long term challenges. Moreover, the obsession with pointless argument and trivia in the traditional media, such as culture wars, allows the UK government to keep attention focused on public debt as if it was a life and death matter, effectively ignoring or avoiding real crises in the grossly inadequate public services and the acute absence of fulfilling, well-rewarded jobs in the economy. Indeed, the laudable goal of promoting social cohesion by investing in the public sphere barely figures in any discussion in the UK media. This is a recipe not just for economic and social stagnation but for regression in the face of long-term challenges, such as the shift of the global economic centre of gravity to East Asia, and of the looming catastrophe of global warming.

There are of course some stray signs to the contrary outside the UK. In the US, the new administration is planning to spend massive sums of money to prevent mass unemployment and to invest in its run-down infrastructure. It is thereby outflanking the opportunism of right wing populism. Remarkably, in the country that invented neoliberalism, the size of the budget deficit no longer appears to be determining how much the US Administration is going to spend; the danger of mass unemployment does. Amazingly, even the IMF, the patron saint of neoliberalism, agrees. This is because fiscal rectitude has failed so visibly since the financial crisis that it has undermined not just faith in the State but now in capitalism itself. None other than the CEO of J P Morgan fears for the long term future of American capitalism and society.

In the UK, that realization has not yet dawned, given the nature of the media, and the mediocre intellectual discourse that dominates political discussion in the country. The UK seems to be blissfully unaware that QE (Quantitative Easing), first used by Japan in the 1990s, is common practice across the world with around $ 20 trillion of new money having been introduced into the global economy since 2008 to save it from collapse. The UK looks upon such developments with childish disdain.

In the UK, the ghosts of Hayek and Friedman are never too far from the surface even when the experience of real people ever comes up for discussion in the media. It is the pathological fear of public indebtedness that stalks the nooks and crannies of the country in the guise of responsible governance. It has effectively shut down all sensible discussion of the country’s problems and its future, although for most people the size of the public debt followed by unending austerity has failed to amount to a credible political narrative in the country. It is an obsession primarily of the UK ruling elite that has been elevated to the level of a quasi-religious creed.

Here, it should be emphasized that hardly any Western society or government has managed to cope well with the Covid 19 pandemic, partly because of a lack of preparation and partly because of an inability to decide that the pandemic and saving lives had to take priority over the economy. Against this, autocratic East Asia and quasi-democratic South-East Asia have succeeded in keeping both deaths from the virus and its associated economic dislocation under control.

Yet, these countries have few admirers in either the UK or in the wider Western world. On this basis, only an incorrigible optimist would believe that any Western government or society will be able to meet the daunting challenges of growing inequality or of a weakened social contract as public services wither, and, above all, of devastating global warming that may come sooner than most people expect. The problems facing the world are man-made; hence, within a radically different political and value system they are surely capable of solution (Will Hutton 2015).

As to the future of neoliberal capitalism, there is little doubt that like everything else that has come before, it, too, will eventually fade into history. In the past, capitalism was able to re-invent itself, for example in the 1930s, with Keynesian pump-priming and prevented mass unemployment, and after World War II with the creation of the welfare State, because the ruling elites were willing to do so as they feared revolution. In the UK, a torn social fabric needs a new social contract.

Above all else, a modern version of the Enlightenment is needed to create a gentler, more empathetic society in the developed countries in which the weak, such as the unemployed, migrants and refugees, are not demonized for the sake of fickle political advantage. For there to be social and political stability and a sense of hope in capitalist societies a different, much more humane, polity inspired by social justice will, sooner or later, have to be fashioned. To this end, education and an intelligent social media will have to create a climate of opinion so that politics is not left to the mercy of corporate interests, to the purveyors of outlandish conspiracy theories and in the hands of incompetent politicians.

Between 400 and 700 years ago the people of Easter Island (now a part of Chile) were talented canoeists and travelled far and wide over the South Pacific, collecting massive stone slabs that they then carved into human-like figures, presumably for worship. They discovered that in their zeal to travel and transport these slabs home they had succeeded in cutting down all the trees to make the canoes. Legend has it that their civilization collapsed within a few years leaving the massive stone figures that they worshipped as lonely sentinels of their past. It is a lesson that all capitalist societies need to heed if they are to meet the daunting challenges facing them.