Amna’s prose has this genuine decorative quality and power. It’s almost exhilarating to read through her several paragraphs and sentence structure, with these very fresh language twists advancing ideas and moving the story forward quickly, but also making you pause and read again – something I felt in a very different book by Philp Roth’s Everyman. Roth’s protagonist (like Amna’s Hira) reflects about his entire life and the choices he made in retrospect, critically reflecting upon the places where he lived and worked, and the relationships that he lost and saved by the end of his life. Thankfully nothing happens to Hira, but her months in disease put her in place to reflect upon the life that she left back in Rawalpindi. In the process, she is able to lay bare what we feel but cannot share as South Asians in their first engagement with America.

We come across what South Asians think as they buy food at the airports or meet people at their schools or hang out with them over picnics. Every experience is new but loaded for its value, as an experience thought from the standpoint of their past experience – which can even be tiring, as Hira says.

Many great writers opted to write about themselves or their community most of the time, Khushwant Singh, Rohintan Mistry and Bapsi Sidhwa in our own South Asian tradition of English writers and Amna is no exception as her details sound partially biographical. She delivers her debut with great authority and confidence and makes brave choices in experimenting with language and form. The first-person protagonist without ties to her own timeframe, but not too distant from that too, or treating the part of the chapters dealing with the disease separately without loosing the flow in the story line, or those finer details which makes every sentence essential and not additional – that makes the details so much more enriching to the text. The over-lit airports, the airline food, the beginning of a first friendship with people who least understand your culture and meeting your classmates who are far less ambitious than you about their careers! And the question as to how much Muslimness we can practically practice outside our home and in what ways. And most importantly: how much of your identity and its politics will you carry (or do not wish to carry) as begin your new life in the West?

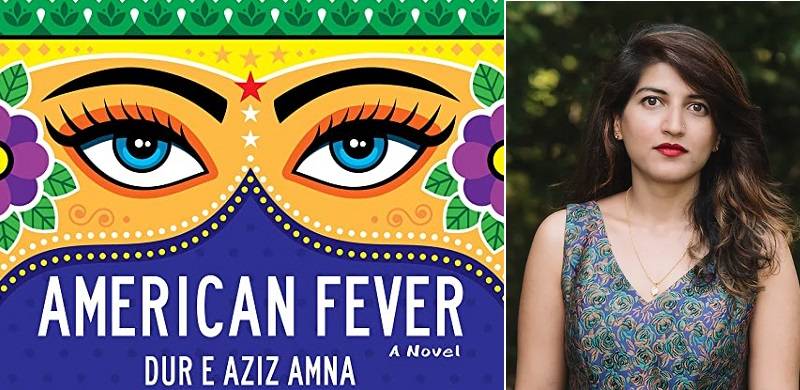

Title: American Fever

Author: Dur E Aziz Amna

Publishers: Sceptre (2022)

Pages: 248

There are many relatively smaller but important parts of the storyline written with a great depth. This is a snapshot of Pakistanis living in New Jersey in their own Muslim bubble, living relatively affluent but disengaged lives with their wider American cultural and political context. You see this crowd all around North America and more particularly in the UK at places like East London – where I saw even Gourmet Bakers selling Halwa Puri in Ilford with its Pakistani buyers watching round-the-clock Geo and ARY TV at their homes and attending their own sect’s mosque – even if they have to go slightly far from their own vicinity. Sipping doodh patti in Tooting’s desi hotels makes you forget home but remember it too, because you have never left it in the first place. Your very existence outside your comfort zone could never flourish beyond a few hours at work, where WhatsApp messages in Urdu still keep you grounded about political feuds in Islamabad’s national assembly or in Peshawar’s municipal elections. You watch them in hordes on your flight to Birmingham where I once saw a family of 15 returning from a wedding in Gujar Khan carrying 38 suitcases. I counted them because I got my back in the end!

Therefore, the larger point in Amna’s work is about how our traditional mind would negotiate with foreign cultures, especially when our own internal familial understanding of the world is so orthodox. But on other hand, the dilemma which often Hira had while living in small-town America was around her (limited) life in Oregon – where despite slightly better school facilities and freedoms for young people, she found it equally (but surely differently) bigoted and constraining.

Then is it still valid to aspire to a life based on broad generalised promises of a better life, whereas in actual fact what you are experiencing and thinking of is a surface-level understanding and interactions – all coming at the expense of a deep and contextualised life that people in their own traditional settings in South Asian contexts have been living for centuries? Where even a local song at a wedding could be as old as few hundred years?

The same is true for many academics and writers based in the West, where despite their prolonged engagements, they end up producing writings based on their memories and stories of their own people – something which Mushtaq Yusufi mentioned in his works in the early 1990s once he returned to Karachi after spending over 12 years in the UK. Amna deals with it in her final page: another great example of the power of prose which makes you pause. You feel deeply satisfied but injured too, for the choices that we humans make. Amna writes:

Why move if you do not wish for places to change you? But perhaps you leave to find out what does not change, the discontent and itch that are constant. You move only to discover, amidst the waiting and the hoping, and the dashing of that hope, that there is only place the boat will dock. Wherever you go, there you are.

The tiredness of ages burrows inside of me. I take a deep breath, pumping air into scarred lungs that will permanently bear witness to disease. I wish to remain unmoving, still and static, as contents shift and rearrange themselves around me, as everything changes and nothing does.

I plead with my limbs to walk these final yards home.

How beautiful.

The arrival of this newer version of Jhumpa Lahiri – whose debut Interpreter of Maladies had dazzled the literary scene back then – , Amna’s book is a major new entry in the star-studded tradition of the South Asian novel. And she will remain a writer to watch for in the years to come.