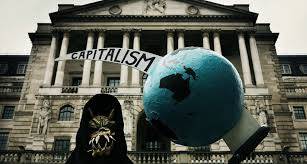

Led by the UK, after the victory of Margaret Thatcher in 1979, and followed by the US, with the victory of Ronald Reagan in 1980, privatization of State-owned assets, lower welfare spending, deregulation and lowering the burden of taxation on the rich were put in train in the two countries. Trade unions came under severe pressure and their membership plummeted. In 1991, with the collapse of the USSR and its Eastern European allies the West confidently asserted that capitalism and its cousin ‘Western’ liberal democracy had won (Francis Fukuyama 1992). Outside the realm of domestic policy the field was now open to pursue globalization whereby the production of goods and services would go to the lowest cost or, in other words, effectively to the most deregulated/liberalized countries. In due course, globalization would enable employers to ‘optimize’ their arrangements not just to pay the least tax but also to reduce benefits for their employees and willy-nilly to sideline environmental obligations in the process. The result in the UK was a steady erosion of labour standards compared to what had existed before and compared to other European countries with the UK opting out of the EUs Social Chapter which had laid out minimum standards of rights for workers, such as the length of the working week, sick pay and holiday entitlements. Unsurprisingly, in the decade beginning 2010 the term ‘precariat’ had come into being to describe the growing number of workers on low-paying insecure jobs.

The neoliberal revival: impact on the UK economy

The UK was the first economy in the world to industrialize. It was, however, overtaken by the US in the latter half of the 19th and by Germany in the early part of the 20th century. But, between 1800 and 1900, on the strength of its navy, the country had acquired for itself a vast array of colonial possessions across the globe. These colonies were a rich source of raw materials to begin with and, over time, became an equally lucrative collection of markets into which access was automatically available to UK products. An interesting fact to bear in mind also is that the UK as a colonial power became not just a purveyor of manufactured goods but also of connected services, such as legal, finance, shipping and insurance, so that from the beginning of the 20th century the UK was not only a major manufacturing economy but had indirectly created the base for the later development of rent-seeking activities that these services created within its own borders.

By the 1950s, the two world wars and the ending of colonialism had put the UK economy on a rocky path. Financially bankrupt now, the country’s ruling elite could not develop a coherent strategy to promote broad-based growth as a way of sustaining their own special privileges. For instance, neither the institution of a more egalitarian social construct between 1945 and 1980, nor attaching itself to the more dynamic EEC in 1973, ultimately proved successful in strengthening the economy. The relative performance of the UK economy, especially in productivity, remained stubbornly unchanging, especially compared to Germany, with its superior industrial relations and higher investment in skills. Even France, the Netherlands and later Italy in Europe and Japan further afield, where the notion of profit-maximization had a more long-term tenor, performed better in the global economy.

Perhaps not as a deliberate result of policy, the economy coincidentally began to deindustrialize from 1980 onwards and by 2000 the UK had become a predominantly service-oriented country heavily geared towards finance. The City of London flourished but the industrial working class had effectively disappeared from the scene. Moreover, other than in finance, few new jobs were created in the economy and these were predominantly in low value-added, non-traded services, such as retail, wholesale distribution, bars, cafes and call centres with many, close to one million, euphemistically classified as self-employed, earning well below median incomes. And, as traditional manufacturing declined, the trade balance deteriorated financed with inflows of money of increasingly doubtful provenance. The City of London, along with several tax havens closely associated with the UK, became destinations for the world’s wealthy and corrupt. In the face of these developments, as the overall economy began to flat-line, the country’s ruling elite realized that, if nothing else, they needed to consolidate their own economic position and social status.

As mentioned earlier, neoliberalism in the UK had its genesis in the inflationary pressures that beset the economy in the late 1960s as productivity growth stalled and as the country began to lag behind its competitors; not in the lacklustre performance of the economy in an absolute sense. In the right wing media, the usual culprits were rounded up – primarily trade union militancy. But the resulting poor industrial relations were the outcome of poor worker skills and a lack of investment in training and infrastructure. In these areas there was little or no coherent policy follow-up, either politically at the level of the State or at the corporate level. The UK continued to under-invest compared to its European neighbours. But, neoliberal economists, and others, then found a more plausible-sounding culprit – fiscal profligacy and the regulatory burden. The new argument was that the economy had a ‘natural’ rate of productivity growth and adding liquidity in the economy, via budget deficits, would only lead to higher inflation. On this basis, a drastic set of policy measures were taken to reverse the high public spending of the post-World War II Keynesian era. The policy mantra now became: control or drastically cut public spending and reduce the regulatory burden on the private sector.

These prescriptions centred round not only on fiscal rectitude per se but in its wider, practical ramifications introduced an excessively strong anti-inflation monetary policy stance built on significantly higher real interest rates. With the privatization of State assets and dismantling of restrictions on corporate activity through a programme of deregulation, the supposed aim was to achieve higher productive efficiency by removing the ‘dead’ hand of the State from the economy and to incentivise entrepreneurship and investment. Deregulation, helped along by flexible labour standards, would mean that the UK economy would become more easily integrated with global investment and supply chains. The implicit assumption was that all State spending would now have to be ‘afforded’ as in private households. Whether all this was actually true was another matter and it is worth noting that, save for a few skeptical voices, neoliberal ideas were accepted with minimal criticism in the UK media.

In rerospect, the putative benefits of lower taxation and fiscal rectitude have not only proved elusive but, more damagingly, their indirect social and economic costs have been severe. First, the prolonged experience with high interest rates in the early 1980s to squeeze inflation out of the system led not only to the deepest recession on record in the UK with over 3 million unemployed but large, speculative capital inflows attracted by the high interest rate environment designed primarily as an anti-inflation policy, grossly over-valued the pound and helped in the decimation of manufacturing and to persistent external deficits. Second, public housing and utilities were privatized so that living costs rose for the poor while simultaneously converting the profits from these enterprises into income and dividends for their new owners and private investors, rather than be reinvested in the housing stock and utilities themselves. Third, with the revenues from privatization and the temporary bonanza of North Sea oil and gas the overall burden of direct taxation on the rich and on corporations was sharply reduced giving a major boost to inequality. Retraining programmes set up by the government to counter the collapse of traditional industries were patchy and insufficient and, hence, had little impact. This was not all. The whole notion of social justice itself was downgraded to play second fiddle to the needs of economic efficiency (John Plender 2015).

In the UK as well as elsewhere one of the noteworthy side-effects of neoliberalism has been that it has seamlessly morphed into monopolization. With little new private investment the UK – for instance, most FDI inflows into the country have taken over existing assets rather than create new ones and the ruling elite have cartelized wherever and to whatever extent possible – an objective made easier by the fact that, as most services are not internationally traded, monopolies and rent-seeking have been able to thrive without the fear of foreign competition. In the UK perhaps the most enduring form of rent-seeking, and one with which nearly all countries in the world would be familiar, is rent derived from the ownership and/or control of land. We are not talking of farm land where incomes would be constrained by international prices, but of urban or semi-urban land on which apartment blocks, houses and industrial facilities are built. In the UK, because of the historically slow pace of house-building, except in the 1950s and 1960s, it is an asset class that is always scarce in relation to demand and, hence, delivers high returns both in the form of rents and in capital gains (Brett Christophers 2020).

Rent-seeking in land is now massive in the UK. But, the outstanding source of income from land is in the form of capital gains made via the simple device of obtaining planning permission to convert farm land, especially land near towns and cities into residential land and then ‘sitting’ on the permissions. In the UK this is known as ‘land banking’ and forms a major portion of the assets of construction companies. Another popular new device is the conversion of freehold ownership into leaseholds, thus providing the owners with a steady stream of rents for years into the future.

In the early years of neoliberalism the initial focus of deregulation was on financial services. This rapidly led to the phenomenon of the ‘financialization’ of the UK economy. The traditional function of finance, in the UK and elsewhere, was to intermediate between savers and investors and to furnish the latter with finance both for short-term working capital purposes and for long-term investment in fixed assets. The former was the preserve of commercial banks while the latter was in the hands of merchant/investment banks that facilitated the interaction of investors with the capital markets. However, deregulation not only blurred the lines between these activities and thus multiplied systemic risk within the financial system, such as the use of the ‘originate and distribute model’ where the originating bank or banks, instead of holding the loan package sell them on as securities in the secondary market. As profits from the latter ballooned, UK-based financial institutions expanded massively into the new areas of securities’ issuance and trading and, in the process, downgraded their less profitable, traditional lending activities. Indeed, non-financial enterprises also jumped into financial activities as a way of boosting profits (Brett Christophers op.cit.).

The neoliberal revival: impact on the UK economy

The UK was the first economy in the world to industrialize. It was, however, overtaken by the US in the latter half of the 19th and by Germany in the early part of the 20th century. But, between 1800 and 1900, on the strength of its navy, the country had acquired for itself a vast array of colonial possessions across the globe. These colonies were a rich source of raw materials to begin with and, over time, became an equally lucrative collection of markets into which access was automatically available to UK products. An interesting fact to bear in mind also is that the UK as a colonial power became not just a purveyor of manufactured goods but also of connected services, such as legal, finance, shipping and insurance, so that from the beginning of the 20th century the UK was not only a major manufacturing economy but had indirectly created the base for the later development of rent-seeking activities that these services created within its own borders.

By the 1950s, the two world wars and the ending of colonialism had put the UK economy on a rocky path. Financially bankrupt now, the country’s ruling elite could not develop a coherent strategy to promote broad-based growth as a way of sustaining their own special privileges. For instance, neither the institution of a more egalitarian social construct between 1945 and 1980, nor attaching itself to the more dynamic EEC in 1973, ultimately proved successful in strengthening the economy. The relative performance of the UK economy, especially in productivity, remained stubbornly unchanging, especially compared to Germany, with its superior industrial relations and higher investment in skills. Even France, the Netherlands and later Italy in Europe and Japan further afield, where the notion of profit-maximization had a more long-term tenor, performed better in the global economy.

Perhaps not as a deliberate result of policy, the economy coincidentally began to deindustrialize from 1980 onwards and by 2000 the UK had become a predominantly service-oriented country heavily geared towards finance. The City of London flourished but the industrial working class had effectively disappeared from the scene. Moreover, other than in finance, few new jobs were created in the economy and these were predominantly in low value-added, non-traded services, such as retail, wholesale distribution, bars, cafes and call centres with many, close to one million, euphemistically classified as self-employed, earning well below median incomes. And, as traditional manufacturing declined, the trade balance deteriorated financed with inflows of money of increasingly doubtful provenance. The City of London, along with several tax havens closely associated with the UK, became destinations for the world’s wealthy and corrupt. In the face of these developments, as the overall economy began to flat-line, the country’s ruling elite realized that, if nothing else, they needed to consolidate their own economic position and social status.

As mentioned earlier, neoliberalism in the UK had its genesis in the inflationary pressures that beset the economy in the late 1960s as productivity growth stalled and as the country began to lag behind its competitors; not in the lacklustre performance of the economy in an absolute sense. In the right wing media, the usual culprits were rounded up – primarily trade union militancy. But the resulting poor industrial relations were the outcome of poor worker skills and a lack of investment in training and infrastructure. In these areas there was little or no coherent policy follow-up, either politically at the level of the State or at the corporate level. The UK continued to under-invest compared to its European neighbours. But, neoliberal economists, and others, then found a more plausible-sounding culprit – fiscal profligacy and the regulatory burden. The new argument was that the economy had a ‘natural’ rate of productivity growth and adding liquidity in the economy, via budget deficits, would only lead to higher inflation. On this basis, a drastic set of policy measures were taken to reverse the high public spending of the post-World War II Keynesian era. The policy mantra now became: control or drastically cut public spending and reduce the regulatory burden on the private sector.

These prescriptions centred round not only on fiscal rectitude per se but in its wider, practical ramifications introduced an excessively strong anti-inflation monetary policy stance built on significantly higher real interest rates. With the privatization of State assets and dismantling of restrictions on corporate activity through a programme of deregulation, the supposed aim was to achieve higher productive efficiency by removing the ‘dead’ hand of the State from the economy and to incentivise entrepreneurship and investment. Deregulation, helped along by flexible labour standards, would mean that the UK economy would become more easily integrated with global investment and supply chains. The implicit assumption was that all State spending would now have to be ‘afforded’ as in private households. Whether all this was actually true was another matter and it is worth noting that, save for a few skeptical voices, neoliberal ideas were accepted with minimal criticism in the UK media.

In rerospect, the putative benefits of lower taxation and fiscal rectitude have not only proved elusive but, more damagingly, their indirect social and economic costs have been severe. First, the prolonged experience with high interest rates in the early 1980s to squeeze inflation out of the system led not only to the deepest recession on record in the UK with over 3 million unemployed but large, speculative capital inflows attracted by the high interest rate environment designed primarily as an anti-inflation policy, grossly over-valued the pound and helped in the decimation of manufacturing and to persistent external deficits. Second, public housing and utilities were privatized so that living costs rose for the poor while simultaneously converting the profits from these enterprises into income and dividends for their new owners and private investors, rather than be reinvested in the housing stock and utilities themselves. Third, with the revenues from privatization and the temporary bonanza of North Sea oil and gas the overall burden of direct taxation on the rich and on corporations was sharply reduced giving a major boost to inequality. Retraining programmes set up by the government to counter the collapse of traditional industries were patchy and insufficient and, hence, had little impact. This was not all. The whole notion of social justice itself was downgraded to play second fiddle to the needs of economic efficiency (John Plender 2015).

In the UK as well as elsewhere one of the noteworthy side-effects of neoliberalism has been that it has seamlessly morphed into monopolization. With little new private investment the UK – for instance, most FDI inflows into the country have taken over existing assets rather than create new ones and the ruling elite have cartelized wherever and to whatever extent possible – an objective made easier by the fact that, as most services are not internationally traded, monopolies and rent-seeking have been able to thrive without the fear of foreign competition. In the UK perhaps the most enduring form of rent-seeking, and one with which nearly all countries in the world would be familiar, is rent derived from the ownership and/or control of land. We are not talking of farm land where incomes would be constrained by international prices, but of urban or semi-urban land on which apartment blocks, houses and industrial facilities are built. In the UK, because of the historically slow pace of house-building, except in the 1950s and 1960s, it is an asset class that is always scarce in relation to demand and, hence, delivers high returns both in the form of rents and in capital gains (Brett Christophers 2020).

Rent-seeking in land is now massive in the UK. But, the outstanding source of income from land is in the form of capital gains made via the simple device of obtaining planning permission to convert farm land, especially land near towns and cities into residential land and then ‘sitting’ on the permissions. In the UK this is known as ‘land banking’ and forms a major portion of the assets of construction companies. Another popular new device is the conversion of freehold ownership into leaseholds, thus providing the owners with a steady stream of rents for years into the future.

In the early years of neoliberalism the initial focus of deregulation was on financial services. This rapidly led to the phenomenon of the ‘financialization’ of the UK economy. The traditional function of finance, in the UK and elsewhere, was to intermediate between savers and investors and to furnish the latter with finance both for short-term working capital purposes and for long-term investment in fixed assets. The former was the preserve of commercial banks while the latter was in the hands of merchant/investment banks that facilitated the interaction of investors with the capital markets. However, deregulation not only blurred the lines between these activities and thus multiplied systemic risk within the financial system, such as the use of the ‘originate and distribute model’ where the originating bank or banks, instead of holding the loan package sell them on as securities in the secondary market. As profits from the latter ballooned, UK-based financial institutions expanded massively into the new areas of securities’ issuance and trading and, in the process, downgraded their less profitable, traditional lending activities. Indeed, non-financial enterprises also jumped into financial activities as a way of boosting profits (Brett Christophers op.cit.).