Religious politics has played an important role in the development of art in the Muslim world. Since its inception as an independent country in 1947, Pakistan has faced multiple challenges, including the role of religion in its political and cultural fabric. There is a continuing debate on this issue in the light of Quaid-e-Azam’s vision of religious balance – who wanted a state where people of all religions could freely practice their beliefs. Denying this aimed-for religious harmony in the newly created country, the religious political parties impose their mindset at all the social and cultural forums which affected the art scene of Pakistan generally and calligraphic art particularly. After 75 years, the effects of such religious conflicts is observed in the Pakistani art scene with special reference to the popularly known Art of Islamic calligraphy.

After 1979, there was a forceful religio-political movement that ended in the longest period of martial law Pakistan had ever witnessed. The religion card was played by General Zia-ul-Haq to its fullest, to legitimise his dictatorship at that time. In the chaotic art world of the time, calligraphy was taken up as one form of visual art which had no clash with Islamic ideology. Since then, religion has been pivotal in the development of art forms in Pakistan and calligraphic painting has carved a permanent niche for itself here. Calligraphic art has come a long way since then, and today relies less on its religious content, but this has done little to dispel the general notion which links it with religion and makes it a very popular art form deeply embedded in the religious politics of the country. Every year, a series of Calligraphy exhibitions are held in various art galleries just before and during the holy month of Ramadan – putting a stamp on its status.

Generally believed to be the genre which is very popular commercially, calligraphy exhibitions are held separately and seldom with mainstream art. The art is referred with a prefix of Islamic and in the process eliminates all other forms which it may take. Urdu, Punjabi, Pashto, Sindhi and many other regional languages are written in Arabic script but somehow, only the calligraphers writing the Quranic verses are considered calligraphers. The polarised calligrapher community refers to this art as Islamic Calligraphy, Classic Calligraphy, Calligraphic art, Calligraphic paintings and simply as Calligraphy. However, the popular perception is inclined towards the religious implications, making it a commercially popular form of art in a country where Muslims are in majority.

Calligraphy in Arabic script developed into a refined art over a long period of time starting from the pre-Islamic era. From the haphazard early scripts to the more proportioned and regulated styles, Arabic calligraphy underwent many stylistic changes. From its earliest purpose of writing the Quranic text, the art of calligraphy became an essential part of Muslim cultures in official record-keeping, manuscript production, education, architectural and object ornamentation, and later on as a diversified art form. The recent discovery of Quran manuscripts belonging to the 7th century AD indicates that writing is indeed the oldest art form in Muslim world. Having said this, it is also important to know that the Quran was not the only manuscript written in this way, and non-religious texts were also written for various purposes. However, a number of different styles of writing were used for writing religious and secular texts – and scribes and calligraphers enjoyed an exalted status in the society.

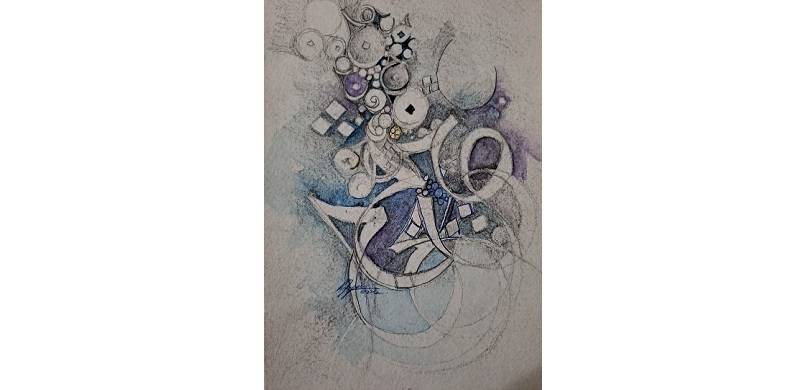

With the advent of printing technologies; the art of classic calligraphy was declining in the Muslim world since the 19th century. The West abandoned the manual writing since the invention of the printing press. The use of text was rediscovered as an art expression after WWI as a protest against the prewar redundant and stale cultural and political values. After WWII, the trend of using letter forms in art is linked with the post-colonial era as a political statement. The influence of Western art imagery promoted a search for Muslim identity based on Islamic heritage. This thought initiated the usage of Arabic alphabets as a formal design element which developed into an abstract art form resembling calligraphy. In the Arab world, this art movement was called ḥurūfiya. It took its inspiration from the Western artists and movements like Paul Klee and Dadaism, which used bright colours and letter forms in art works. Later on, the trend of using Arabic letter forms emerged in Pakistan where artists like Shemza, Ramey and Shakir Ali started using letter forms in paintings – but with the passage of time it took a more religious form, which displeased the practitioners of classic calligraphy.

The religious politics of the 1980s propelled artists who had some knowledge of writing in Arabic script to practice calligraphic art rather than to totally abandon their artistic skills. Aftab Ahmed, Shafique Farooqi, Bashir Moojid, Neyar Ehsan Rashid, Ibn e-Kalim, Shakil Ismail, Aslam Kamal and Sardar Mohammad are some of the artists who rose to prominence during this time. There were still other artists who adopted a calligraphic style closely linked to abstract painting and action painting of the West. Sadequain and Gulgee and the followers of their school are good examples. These artists looked at calligraphic art as a survival of their creative expression. However, classic calligraphers kept working in their particular style and focused on the religious texts. Their art was seldom displayed in art galleries and was termed static and non-artistic by mainstream artists and gallery owners.

As far as calligraphic art in Pakistan is concerned, the early artists were not trained calligraphers, and the classical calligraphers had little training in painterly skills. In rare cases when an artist is trained in both calligraphy and art, his/her understanding is reflected in the art which they produce. But major artists such as Shemza, Ramey, Gulgee, and Shakir Ali were not trained calligraphers. For this reason, it is not appropriate to put the onus of a revival of Islamic calligraphy on these calligraphic artists, they just went along the religio-political sentiment of their time. On the other hand, the practitioners of classic calligraphy rarely exhibit their work, keeping it strictly guarded as religious art. Rasheed Butt, Irfan Qureshi are some of the many who are holding on to the art of classic calligraphy in the present-day art world.

Despite the conflict between the classical calligraphers and the artist community, all the calligraphic painters have helped to promote an interest in traditional Muslim calligraphy in the postmodern world, and the art is yet again taking a new turn. Arif Khan, Jamshed Qaiser, Muneeb Ali, Bin Qalander, Ijaz Malik, Chitra Pritam and many others are working as contemporary calligraphic artists producing meaningful compositions with a tilt towards religious texts.

The tradition set over a period of 40 years of holding calligraphy exhibitions in the month of Ramadan is still alive. Recent exhibitions at prominent art galleries of Lahore are a reflection on the relevance of this art form with the religious politics of the country. It may not be true to suggest that the calligraphic artists have revived the art of Islamic calligraphy, but it will not be so untrue to say that a genuine interest has developed in the artist community and the alphabets are used in paintings and sculptures by mainstream artists like Amin Gulgee. All said and done; the fact is that calligraphy of any type is a very popular art form and its popularity is fueled by the religious-political sentiment in Pakistan.

After 1979, there was a forceful religio-political movement that ended in the longest period of martial law Pakistan had ever witnessed. The religion card was played by General Zia-ul-Haq to its fullest, to legitimise his dictatorship at that time. In the chaotic art world of the time, calligraphy was taken up as one form of visual art which had no clash with Islamic ideology. Since then, religion has been pivotal in the development of art forms in Pakistan and calligraphic painting has carved a permanent niche for itself here. Calligraphic art has come a long way since then, and today relies less on its religious content, but this has done little to dispel the general notion which links it with religion and makes it a very popular art form deeply embedded in the religious politics of the country. Every year, a series of Calligraphy exhibitions are held in various art galleries just before and during the holy month of Ramadan – putting a stamp on its status.

Generally believed to be the genre which is very popular commercially, calligraphy exhibitions are held separately and seldom with mainstream art. The art is referred with a prefix of Islamic and in the process eliminates all other forms which it may take. Urdu, Punjabi, Pashto, Sindhi and many other regional languages are written in Arabic script but somehow, only the calligraphers writing the Quranic verses are considered calligraphers. The polarised calligrapher community refers to this art as Islamic Calligraphy, Classic Calligraphy, Calligraphic art, Calligraphic paintings and simply as Calligraphy. However, the popular perception is inclined towards the religious implications, making it a commercially popular form of art in a country where Muslims are in majority.

Calligraphy in Arabic script developed into a refined art over a long period of time starting from the pre-Islamic era. From the haphazard early scripts to the more proportioned and regulated styles, Arabic calligraphy underwent many stylistic changes. From its earliest purpose of writing the Quranic text, the art of calligraphy became an essential part of Muslim cultures in official record-keeping, manuscript production, education, architectural and object ornamentation, and later on as a diversified art form. The recent discovery of Quran manuscripts belonging to the 7th century AD indicates that writing is indeed the oldest art form in Muslim world. Having said this, it is also important to know that the Quran was not the only manuscript written in this way, and non-religious texts were also written for various purposes. However, a number of different styles of writing were used for writing religious and secular texts – and scribes and calligraphers enjoyed an exalted status in the society.

With the advent of printing technologies; the art of classic calligraphy was declining in the Muslim world since the 19th century. The West abandoned the manual writing since the invention of the printing press. The use of text was rediscovered as an art expression after WWI as a protest against the prewar redundant and stale cultural and political values. After WWII, the trend of using letter forms in art is linked with the post-colonial era as a political statement. The influence of Western art imagery promoted a search for Muslim identity based on Islamic heritage. This thought initiated the usage of Arabic alphabets as a formal design element which developed into an abstract art form resembling calligraphy. In the Arab world, this art movement was called ḥurūfiya. It took its inspiration from the Western artists and movements like Paul Klee and Dadaism, which used bright colours and letter forms in art works. Later on, the trend of using Arabic letter forms emerged in Pakistan where artists like Shemza, Ramey and Shakir Ali started using letter forms in paintings – but with the passage of time it took a more religious form, which displeased the practitioners of classic calligraphy.

The religious politics of the 1980s propelled artists who had some knowledge of writing in Arabic script to practice calligraphic art rather than to totally abandon their artistic skills. Aftab Ahmed, Shafique Farooqi, Bashir Moojid, Neyar Ehsan Rashid, Ibn e-Kalim, Shakil Ismail, Aslam Kamal and Sardar Mohammad are some of the artists who rose to prominence during this time. There were still other artists who adopted a calligraphic style closely linked to abstract painting and action painting of the West. Sadequain and Gulgee and the followers of their school are good examples. These artists looked at calligraphic art as a survival of their creative expression. However, classic calligraphers kept working in their particular style and focused on the religious texts. Their art was seldom displayed in art galleries and was termed static and non-artistic by mainstream artists and gallery owners.

As far as calligraphic art in Pakistan is concerned, the early artists were not trained calligraphers, and the classical calligraphers had little training in painterly skills. In rare cases when an artist is trained in both calligraphy and art, his/her understanding is reflected in the art which they produce. But major artists such as Shemza, Ramey, Gulgee, and Shakir Ali were not trained calligraphers. For this reason, it is not appropriate to put the onus of a revival of Islamic calligraphy on these calligraphic artists, they just went along the religio-political sentiment of their time. On the other hand, the practitioners of classic calligraphy rarely exhibit their work, keeping it strictly guarded as religious art. Rasheed Butt, Irfan Qureshi are some of the many who are holding on to the art of classic calligraphy in the present-day art world.

Despite the conflict between the classical calligraphers and the artist community, all the calligraphic painters have helped to promote an interest in traditional Muslim calligraphy in the postmodern world, and the art is yet again taking a new turn. Arif Khan, Jamshed Qaiser, Muneeb Ali, Bin Qalander, Ijaz Malik, Chitra Pritam and many others are working as contemporary calligraphic artists producing meaningful compositions with a tilt towards religious texts.

The tradition set over a period of 40 years of holding calligraphy exhibitions in the month of Ramadan is still alive. Recent exhibitions at prominent art galleries of Lahore are a reflection on the relevance of this art form with the religious politics of the country. It may not be true to suggest that the calligraphic artists have revived the art of Islamic calligraphy, but it will not be so untrue to say that a genuine interest has developed in the artist community and the alphabets are used in paintings and sculptures by mainstream artists like Amin Gulgee. All said and done; the fact is that calligraphy of any type is a very popular art form and its popularity is fueled by the religious-political sentiment in Pakistan.