"Privacy is not merely a personal predilection; it is an important functional requirement for the effective operation of social structure.” - Robert Merton

The advent of technology has altered the way in which we live our lives and has transformed how we communicate, from social networking platforms to messaging and video conferencing applications like Zoom and WhatsApp. Despite its brilliance, it hasn’t all been fair sailing, as with these vast advancements have come a few hiccups, leading to controversy.

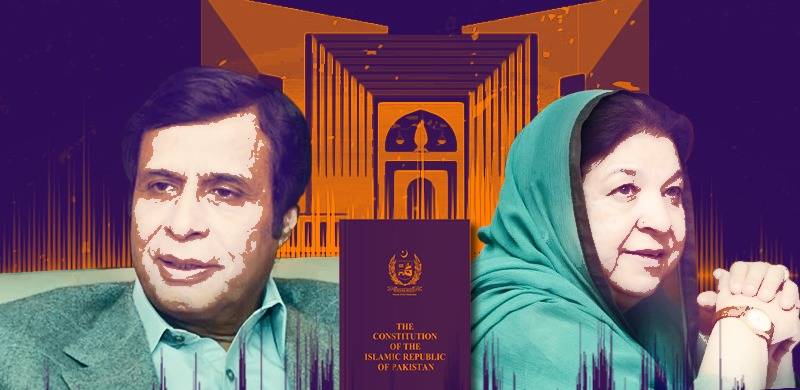

This time around, it’s the mysterious audio leaks of the alleged conversation between Ex-Punjab Chief Minister Chaudhry Pervaiz Elahi which surfaced on the internet, stirring squabbles and white noise as usual. Within days of this, Yasmin Rashid’s conversations were leaked. Unfortunately, these tapped conversations acquired by an anonymous person are readily available on the internet for all to access, and have dampened the image of our country even further. The contents thereof have whisked into existence futile bickering, which generally simmers down, but it led to rows between political supporters, in addition to dinting the already scarce public confidence in the judiciary.

Be that as it may, this scribe is solely concerned with the following questions: does the overt act of phone tapping contravene any of the cardinal rights as enshrined under the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, 1973? If so, to what extent and what are the consequences of such violations?

In order to ascertain the above-mentioned queries, one must first decipher what the term phone tapping means. The Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary defines it as “the activity of secretly fitting a special device to someone’s phone in order to listen to their phone conversations without being noticed.” In other words, phone tapping, also known as wiretapping or interception, is the practice of secretly monitoring and recording telephone conversations without the knowledge or consent of the parties involved.

It can be used for various purposes, including law enforcement investigations, intelligence gathering, and corporate espionage (Gobind case, (1975) 2 SCC 148). In other words, it can be used by state authorities for the purposes of surveillance. Unauthorized phone tapping is generally considered a criminal offence, punishable by imprisonment or fines.

In Pakistan, phone tapping is illegal, except in certain cases where it is authorized by law. Even when it is permitted, the scope is fairly limited and pertains to either anti-state activities or terrorist activities and that too under judicial and executive oversight and is considered illegal without a warrant or court order (Katz case, 389 U.S. 347). Outside such limited areas where it is permitted, surveillance is constitutionally prohibited (Qazi Faez Issa case, PLD 2021 SC 1). As such, intercepting telecommunication between two private individuals is an offence under Sections 25 & 26 of the Telegraph Act, 1885 (‘Telegraph Act’), Section 31 of the Pakistan Telecommunication (Re-organization) Act, 1996 (‘Telecommunication Act’) and Section 19 of the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, 2016 ('PECA') which prohibits the unauthorised interception, monitoring, or recording of private communications.

The underlying rationale for criminalising phone tapping, even as a form of surveillance, is that it has the potential to violate various fundamental rights guaranteed under the Constitution, including the right to privacy, the right to life, the freedom of speech, the right to dignity, and other rights. These inalienable fundamental rights are intertwined (Ghulam Mustafa case, 2021 CLC 204 Lahore; Qazi Faez Isa case; and, Mishbah ud Din Zaigham case, 2021 CLD 906 Lahore) when it comes to phone tapping.

While dissenting in the Olmstead case, 277 U.S.438, 478 (1928), Justice Louis Brandeis expressed the right to privacy in the terms that it is a core of freedom and liberty. The right to be let alone is a reflection of the inviolable nature of the human personality. Against this backdrop, the right to privacy is recognized as a cardinal right under Article 14 of the Constitution and is directly impacted by phone tapping and eavesdropping. Thus, any interception of private communications without lawful justification or proper legal authorization contravenes privacy. Such violations can have serious repercussions, such as invasion of personal privacy, disclosure of sensitive or confidential information, and damage to an individual's reputation or relationships.

Additionally, it also infringes upon the right to life, as it may enable surveillance agencies to obtain information that could be used to threaten or harm individuals, consequently violating Article 9. This is especially concerning in cases where the target of the surveillance is a vulnerable or marginalized individual, such as a human rights defender or a journalist.

Freedom of speech and expression is also susceptible to being affected by wiretapping or interception of telephonic communication. Normally, a person talking on the telephone always presumes that his voice is heard only by the person at the other end of the telephone. The telephonic system itself presumes that except for the speaker and the listener, no one else can hear the talks from one end to the other.

As a result, privacy is assured and freedom of expression is guaranteed, since a person may not have the freedom to speak freely in the presence of others. Edward Snowden in his book Permanent Record stated that “Arguing that you don't care about the right to privacy because you have nothing to hide is no different than saying you don't care about free speech because you have nothing to say.” Therefore, the tapping and eavesdropping of telephones also infringes Article 19 (Benazir Bhutto case, PLD 1998 SC 388) because the fear of being monitored and surveilled discourages individuals from expressing their opinions and ideas freely, thus limiting their right to free speech and potentially creating a chilling effect on public discourse.

Finally, the right to dignity as envisaged under Article 14 is also violated, as it may be seen as a form of harassment or stalking that undermines an individual's sense of privacy and personal autonomy. So far as the fundamental right of dignity and privacy are concerned, they are based on the Qur'anic Injunction which restrains a person from entering into another's house without his permission (Surah 24: Verses 27-28). "This command", Justice Fazal Karim writes, in his book the Judicial Review of Public Actions, "becomes in law a prohibition against unjustifiable entry and unreasonable searches and seizures."

In light of the above, although the Telegraph Act and Telecommunication Act allow and regulate the interception of communications, their scope is limited. The legislature, in order to circumvent the human rights of its citizens, went on to promulgate the Investigation for Fair Trial Act in 2013 ('Fair Trial Act'), allowing state authorities to use covert surveillance and human intelligence, property interference, wiretapping and communication interception under the guise of preventing threats to society. However, as noted earlier, this power is not unbridled and subject to limitations (Justice Mansoor Ali Shah’s note in Qazi Faez Issa case).

The legality of phone tapping, eavesdropping, and surveillance in Pakistan has never been at the forefront of litigation, unlike in India where its vires were challenged on the ground that it infringes upon the right to privacy under Article 21 of the Constitution of India. While considering this aspect in People’s Union for Civil Liberties case, AIR 1997 SC 568, Justice Kuldip Singh observed that “Telephone-Tapping is a serious invasion of an individual's privacy… the right to hold telephone conversation… is increasingly susceptible to abuse.”

The Supreme Court of India went on to admonish the practice of phone tapping, labelling it as a blatant invasion of the right to privacy. However, the vires of this aspect of the Telegraph Act, specifically Section 5; Section 54 of the Telecommunication Act and the relevant provisions of the Fair Trial Act seems to have eclipsed our Supreme Court.

It can safely be concluded that the act of phone tapping and eavesdropping can result in serious infringements of an individual's fundamental rights, and these anonymous vigilantes who leak private conversations should be criminally prosecuted under PECA read with Telegraph Act and the Telecommunication Act, especially considering that the overt act is never done with the intent to prevent a threat to society, rather to disturb the harmony between various organs of state. Though it remains to be seen how the Supreme Court deliberates on the matter when it’s taken up.

Reverting to the audio leaks, during the course of writing, certain reports came out that the Federal Investigation Agency is probing into the genuineness or otherwise of the same. Another query surfaces: whether illegally obtained material can be used against a person. The short answer, as held by Justice Nasim Sikandar in Ihsan Yousaf Textile Mills case, 2003 PTD 2037 LAH (5 JJ), is no because the “fruit of a poisonous tree cannot be allowed to be enjoyed. A tree not grown by dint of labour or acquired by lawful means is a poisonous tree and its fruit cannot be allowed to be enjoyed by the offender.”