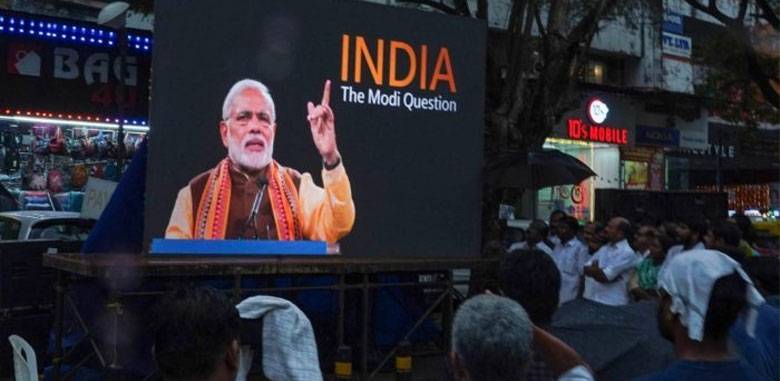

The recently released BBC documentary, India: The Modi Question, has reopened the wounds of Imtiyaz Pathan, who witnessed the brutal killing of Ehsan Jafri during the 2022 Gujarat riots.

Speaking with The Friday Times from Ahmedabad, he recalls that on March 1, 2002, Ahmedabad’s Gulbarg society was up in flames. Ehsan Jafri, a senior Congress leader and a prominent lawyer, had tried everything to save himself as well as local Muslims seeking refuge in his home. “But rioters had other plans – they were throwing stones and killing those outside in his house compound. Jafri called people in power. He called Narendra Modi, who was the chief minister of Gujarat then. I was in his room when he was making frantic calls,” recalls Pathan.

He narrates, Jafri pleaded to thousands of rioters gathered outside his home to leave the hapless people alone… Jafri surrendered, hoping the mob would spare women and children... They pounced on him like packs of hungry wolves, and in no time he was hurled with sticks and punches and dragged to the road... “his body was cut into pieces”.

Pathan’s account made before police and various forums brought Narendra Modi under the scanner. However, last year, the Supreme Court of India gave a clean chit to Modi in the 2002 Gujarat riots. Over the past few years, most of the alleged culprits have either been given a clean chit by the Indian courts or have completed their sentence. Some have also been allowed to walk out on bail. While victims of the riots still await justice.

Unfolding of March 1, 2002

Pathan was a young man of 24 on March 1, 2002. More than twenty years on, his eyes show aging lines and his beard is grey. As he talks with The Friday Times on the riots, his throat chokes and his eyes turn teary.

He says, tensions in the area had started brewing from February 28, a day after the attack and burning of four train bogies in Godhra, about 125 kilometres away from Ahmedabad – “These bogies were carrying Hindu pilgrims and karsevaks (Hindu volunteers) who were returning from Ayodhya, the birthplace of Lord Rama”.

Thousands of men walked into the area, chanting Jai Sri Ram (Hail Lord Rama). They began by looting and burning shops and killing shop owners, he added. “At around 10am, assistant police commissioner MK Tandon arrived in Gulbarg. Jafri Sahib and other elders of the area went out to meet him. Jafri Sahib requested Tandon to move people out of the Gulbarg society to relief camps. Tandon had come in his police vehicle and said that he did not have adequate transport available. But he assured that buses or trucks will be sent soon and curfew will soon be imposed. But till 5pm no police help arrived.”

When war cries filled the air

Slogans like Jai Sri Ram and Har Har Mahadev (Praise Lord Shiva) reverberated across the Gulbarg society. Armed with sticks, stones and fire torches, rioters attacked the area from all sides. There were war cries in Gujarati, like “Miyano Maroo, Miyano Kato (Hit the Miya, cut him into pieces) and Miyano bachwa na jayeya”(No Miya be spared),” recalls Pathan. Miya is a common slang to address Muslims.

He remembers that as the killings increased and women were being dragged out of their houses, the crowd rushed for shelter at Jafri’s home. Women and children were sent on the terrace and young men circled Jafri to protect him.

Jafri meanwhile tried to call for help. Being a legislator, he had the STD calling facility on his phone. His diary had telephone numbers of top politician in India. He knew people in police – “He called up everyone,” says Pathan.

Modi abused Jafri and the telephone line went dead

Jafri made his last call to Modi. “At the end of the call, his eyes were moist and he looked dejected. He told us Modi was abusive. Soon after, his landline went dead,” says Pathan.

When the mob reached his gate, Jafri told them to take him and spare the rest, especially women and children. “Through the mesh of his kitchen window, he told the mob to wait. He did his ablution, offered namaz and stepped out to surrender before the mob. In no time, he was hurled with sticks and punches and dragged – and cut into pieces,” he adds.

While dragging him out, Pathan says, the men were shouting, Jafri haat lag gaya, maro maro (We have got Jarfi. Kill him) – “We never got his corpse back”.

While the government record states 38 people died in Gulbarg, Pathan can count 69 people who were killed on that unfortunate day. However, only 38 charred bodies were recovered. It was difficult to identify the dead.

Victims await compensation

Last year, the Supreme Court of India gave a ‘clean chit’ to Modi for his involvement in the Gujarat riots of 2002. Jafri’s wife, Zakia Jafri, challenged Modi’s ‘clean chit’ in the court but it got dismissed.

The victims of Gulbarg society, belonging to some 18 households, have not returned to their homes. Their burnt houses, with broken windows, falling roofs and overgrown weeds, are still abandoned. People have moved to rented accommodation in ghettos, where they feel their lives are a little secure.

“We lost everything in the riots. To make these houses livable we will need lacs of rupees. The government will not waiver our taxes. There is no electricity and water connection. With a highly polarised atmosphere not just in Gujarat but across the country, will the government be able to provide us security if we go back to our house?” asks Pathan.

Where are the victims of Godhra?

Muslims of the Gulbarg society were penalised for a train burning incident that took place 125 kilometres away from their homes. There are several contradictory reports on the burning of the train in Godhra to ascertain whether the fire was an accident or the Hindu pilgrims were targeted. Reportedly, about 58 people were killed and 48 wounded.

“The government, media houses, civil society groups and NGOs all talk about the train tragedy. Why have the train carnage victims and their families not come out to seek justice? Are they under some kind of pressure from the ruling party?” questions Pathan.

NGOs and civil society members held a conference on the Gujarat riots in Delhi in a few years after the train incident. Families of two victims attended it. Later, they disappeared from public space.

The Gujarat pogrom that lasted for 3 days killed over a thousand people. The government records show more than 2,500 were injured and 233 people are missing.

Some punished, others rewarded

The BBC documentary also mentions police officers like Sanjiv Bhatt and former Director General of Police RB Shreekumar who have been put behind bars over frivolous charges, a price that they are made to pay for submitting before the court the role of Modi in the 2002 riots. “It is well known that police officials like Rakesh Asthana and AK Sharma who worked for Modi during and after the riots, were awarded plum posting in Central Bureau of Investigation after Modi became the PM,” says Pathan.

The government of India fears that the documentary would dent Modi’s political persona as India chairs the G20 this year. The documentary may damage Modi’s image ahead of the general elections next year.

The government of India used all tricks to ban the documentary from screening. Universities in Delhi, including Jawaharlal Nehru University and Jamia Millia Islamia, were at loggerhead with the government over the screening of the film. Though banned, students watched the film on their mobile screens.

Meanwhile a public interest litigation has been filed by senior journalist N. Ram, parliamentarian Mahua Moitra and advocate Prashant Bhushan, which highlights the citizens “fundamental right to view, form an informed opinion, critique, report on and lawfully circulate the contents of the documentary as right to freedom of speech and expression incorporates the right to receive and disseminate information”. The government of India is yet to file its reply in the court.

For Pathan, who has become the voice of Gulbarg, justice is a pipedream – “I tell the story so that the truth remains documented for generations to come.”

Speaking with The Friday Times from Ahmedabad, he recalls that on March 1, 2002, Ahmedabad’s Gulbarg society was up in flames. Ehsan Jafri, a senior Congress leader and a prominent lawyer, had tried everything to save himself as well as local Muslims seeking refuge in his home. “But rioters had other plans – they were throwing stones and killing those outside in his house compound. Jafri called people in power. He called Narendra Modi, who was the chief minister of Gujarat then. I was in his room when he was making frantic calls,” recalls Pathan.

He narrates, Jafri pleaded to thousands of rioters gathered outside his home to leave the hapless people alone… Jafri surrendered, hoping the mob would spare women and children... They pounced on him like packs of hungry wolves, and in no time he was hurled with sticks and punches and dragged to the road... “his body was cut into pieces”.

Pathan’s account made before police and various forums brought Narendra Modi under the scanner. However, last year, the Supreme Court of India gave a clean chit to Modi in the 2002 Gujarat riots. Over the past few years, most of the alleged culprits have either been given a clean chit by the Indian courts or have completed their sentence. Some have also been allowed to walk out on bail. While victims of the riots still await justice.

Unfolding of March 1, 2002

Pathan was a young man of 24 on March 1, 2002. More than twenty years on, his eyes show aging lines and his beard is grey. As he talks with The Friday Times on the riots, his throat chokes and his eyes turn teary.

He says, tensions in the area had started brewing from February 28, a day after the attack and burning of four train bogies in Godhra, about 125 kilometres away from Ahmedabad – “These bogies were carrying Hindu pilgrims and karsevaks (Hindu volunteers) who were returning from Ayodhya, the birthplace of Lord Rama”.

Thousands of men walked into the area, chanting Jai Sri Ram (Hail Lord Rama). They began by looting and burning shops and killing shop owners, he added. “At around 10am, assistant police commissioner MK Tandon arrived in Gulbarg. Jafri Sahib and other elders of the area went out to meet him. Jafri Sahib requested Tandon to move people out of the Gulbarg society to relief camps. Tandon had come in his police vehicle and said that he did not have adequate transport available. But he assured that buses or trucks will be sent soon and curfew will soon be imposed. But till 5pm no police help arrived.”

While dragging him out, Pathan says, the men were shouting, Jafri haat lag gaya, maro maro (We have got Jarfi. Kill him) – “We never got his corpse back”.

When war cries filled the air

Slogans like Jai Sri Ram and Har Har Mahadev (Praise Lord Shiva) reverberated across the Gulbarg society. Armed with sticks, stones and fire torches, rioters attacked the area from all sides. There were war cries in Gujarati, like “Miyano Maroo, Miyano Kato (Hit the Miya, cut him into pieces) and Miyano bachwa na jayeya”(No Miya be spared),” recalls Pathan. Miya is a common slang to address Muslims.

He remembers that as the killings increased and women were being dragged out of their houses, the crowd rushed for shelter at Jafri’s home. Women and children were sent on the terrace and young men circled Jafri to protect him.

Jafri meanwhile tried to call for help. Being a legislator, he had the STD calling facility on his phone. His diary had telephone numbers of top politician in India. He knew people in police – “He called up everyone,” says Pathan.

Modi abused Jafri and the telephone line went dead

Jafri made his last call to Modi. “At the end of the call, his eyes were moist and he looked dejected. He told us Modi was abusive. Soon after, his landline went dead,” says Pathan.

When the mob reached his gate, Jafri told them to take him and spare the rest, especially women and children. “Through the mesh of his kitchen window, he told the mob to wait. He did his ablution, offered namaz and stepped out to surrender before the mob. In no time, he was hurled with sticks and punches and dragged – and cut into pieces,” he adds.

While dragging him out, Pathan says, the men were shouting, Jafri haat lag gaya, maro maro (We have got Jarfi. Kill him) – “We never got his corpse back”.

While the government record states 38 people died in Gulbarg, Pathan can count 69 people who were killed on that unfortunate day. However, only 38 charred bodies were recovered. It was difficult to identify the dead.

Victims await compensation

Last year, the Supreme Court of India gave a ‘clean chit’ to Modi for his involvement in the Gujarat riots of 2002. Jafri’s wife, Zakia Jafri, challenged Modi’s ‘clean chit’ in the court but it got dismissed.

The victims of Gulbarg society, belonging to some 18 households, have not returned to their homes. Their burnt houses, with broken windows, falling roofs and overgrown weeds, are still abandoned. People have moved to rented accommodation in ghettos, where they feel their lives are a little secure.

“We lost everything in the riots. To make these houses livable we will need lacs of rupees. The government will not waiver our taxes. There is no electricity and water connection. With a highly polarised atmosphere not just in Gujarat but across the country, will the government be able to provide us security if we go back to our house?” asks Pathan.

Where are the victims of Godhra?

Muslims of the Gulbarg society were penalised for a train burning incident that took place 125 kilometres away from their homes. There are several contradictory reports on the burning of the train in Godhra to ascertain whether the fire was an accident or the Hindu pilgrims were targeted. Reportedly, about 58 people were killed and 48 wounded.

“The government, media houses, civil society groups and NGOs all talk about the train tragedy. Why have the train carnage victims and their families not come out to seek justice? Are they under some kind of pressure from the ruling party?” questions Pathan.

NGOs and civil society members held a conference on the Gujarat riots in Delhi in a few years after the train incident. Families of two victims attended it. Later, they disappeared from public space.

The Gujarat pogrom that lasted for 3 days killed over a thousand people. The government records show more than 2,500 were injured and 233 people are missing.

Why have the train carnage victims and their families not come out to seek justice? Are they under some kind of pressure from the ruling party?” questions Pathan.

Some punished, others rewarded

The BBC documentary also mentions police officers like Sanjiv Bhatt and former Director General of Police RB Shreekumar who have been put behind bars over frivolous charges, a price that they are made to pay for submitting before the court the role of Modi in the 2002 riots. “It is well known that police officials like Rakesh Asthana and AK Sharma who worked for Modi during and after the riots, were awarded plum posting in Central Bureau of Investigation after Modi became the PM,” says Pathan.

The government of India fears that the documentary would dent Modi’s political persona as India chairs the G20 this year. The documentary may damage Modi’s image ahead of the general elections next year.

The government of India used all tricks to ban the documentary from screening. Universities in Delhi, including Jawaharlal Nehru University and Jamia Millia Islamia, were at loggerhead with the government over the screening of the film. Though banned, students watched the film on their mobile screens.

Meanwhile a public interest litigation has been filed by senior journalist N. Ram, parliamentarian Mahua Moitra and advocate Prashant Bhushan, which highlights the citizens “fundamental right to view, form an informed opinion, critique, report on and lawfully circulate the contents of the documentary as right to freedom of speech and expression incorporates the right to receive and disseminate information”. The government of India is yet to file its reply in the court.

For Pathan, who has become the voice of Gulbarg, justice is a pipedream – “I tell the story so that the truth remains documented for generations to come.”