Only in October of 2022 has Pakistan enacted its first legislation that criminalizes the torture, rape and death of those in the custody of law enforcement. The Torture and Custodial Death (Prevention and Punishment) Bill was first tabled in 2014. Even though Pakistan signed the UN Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UNCAT) in April 2008 and ratified it in June 2010.

Pakistan’s constitution has prohibited the use of torture for extracting confessions under Article 14. However, that remains the only mention of torture in the constitution. Furthermore, the Pakistan Penal Code, Qanun-e-Shahadat Order, and the Code of Criminal Procedure also maintain brief mentions of laws which may be interpreted to deter torture. These mentions remain vague however, such as PPC Section 355, which claims that “assault or criminal force with intent to dishonor person, otherwise than on grave provocation” which is punishable with a prison term that may extend to 2 years, a fine, or both.

The new Act has been enacted at a federal level, so it extends to all of Pakistan. Within the Act, custody defines all places where a person is denied their liberty by a public office or an officer. Thus, it effectively applies to search, arrest and during other seizure procedures as well, while torture and degrading treatment are defined as the standard.

Custodial death includes death not only within custody, but death anywhere which can be attributed directly or indirectly to harm caused by the office in question. Rape includes all sexual abuse done by an officer taking advantage of their position to do this. The interpretation of wording thus makes the act far-reaching.

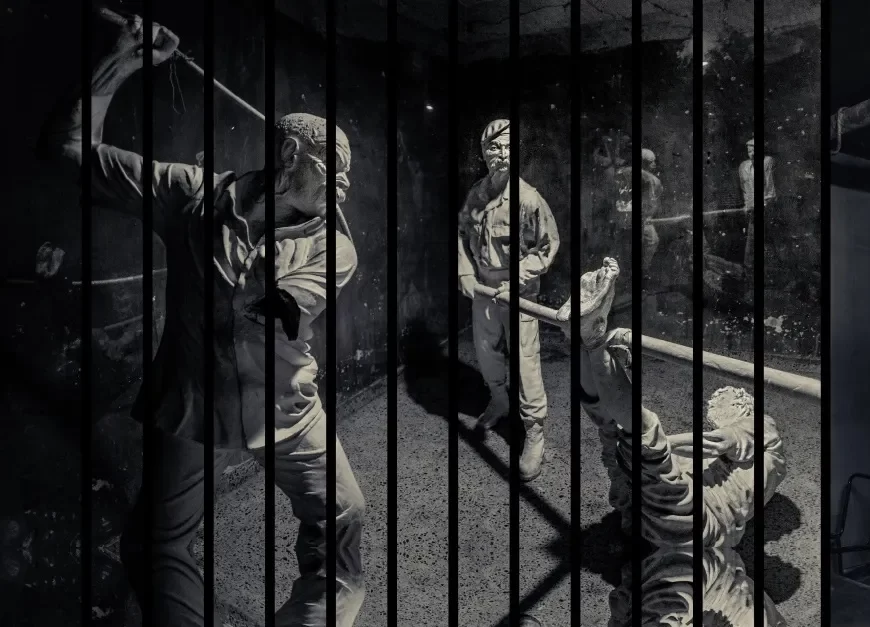

This was a much-needed statute, as torture is not seen as a major issue at large in Pakistani culture. Rather, torture is often glorified as a quick, and “effective” way to interrogate and punish wrongdoers. As showcased in news reports of police brutality from the United States for example, this is a problem even the first world suffers from to a large degree

This exists even though torture fails in all its purposes as a tool of interrogation, as those being tortured will almost always say whatever pleases the officer to stop the torture. Torture is not only physical but also a tool of psychological torment; each complementing the other.

Even torture methods thought to be more “passive” such as solitary confinement and sleep deprivation are not only still extremely harmful to victims in long run, but also still produce false confessions and information which also only serves to hamper appropriate investigations.

Apart from physical injuries and disabilities, victims may also suffer serious mental disorders such as PTSD, and depression among many other severe conditions. Victims may also suffer a loss of memory, and not even remember their own names and homes, as well as lose other skills and functions, in many cases rendering them unable to support their families and their livelihoods.

The harm to the torturers themselves is also understated. Those in power that use torture do not have to be involved in the process of torture itself, rather just give orders. Those who are tasked to carry out the torture will often find themselves suffering from long-lasting psychological harm.

A fairly common misconception is that only high-profile criminals suffer custodial torture. This is factually incorrect. According to various human rights organizations, all sorts of people, whether hardened criminal, petty thiefs, protestors, or just someone caught in the crossfire – have been victimized through custodial torture.

The ubiquity of torture in our public life as a nation can be evidenced through the frequent political victimization of the opposition by the given government of the day, and the clown show that the whole country witnesses throughout every party’s term. The act of using law enforcement agencies as personal thugs fundamentally undermines the democratic process within the country, which can perhaps be seen as the main catalyst for this act.

The problem with extant legislation were blatantly obvious; the law was so blurry and complicated in its nature, that applying it appropriately meant filing a First Information Report (FIR) for custodial torture was unnecessarily complicated, and in-ground realities made it near impossible for the poor and underprivileged class to file. This meant that the officer that had committed torture would face no real consequences. Thus, officers were able to torture, rape, murder and extract confessions under duress, without any viable protocol for the victim or their kin to take up against the officer in question.

Under the Act, the victim may directly report torture as a cognizable crime by the perpetrator; this means the police has the ability to jail the suspect, and can start an investigation against the suspect without awaiting a magistrate’s approval, such is the case for most serious crimes.

However, this is all theoretical as FIRs fall within the domain of the SHO of the station, who may as well deny a member of the general public their right. Further course of action for such persons is so complicated that it becomes nigh impossible to pursue. This is best put on display by the bizarre spectacle that was the inability of even Imran Khan to file an FIR against certain people for attempted murder, even though he had the Chief Minister of his preference in power.

Moreover, the fact remains that the perpetrator of the murder of any underprivileged person under custody is still able to squeeze through the nets of the new legislation. This is facilitated through the mechanisms of Qisas (forgiveness) or Diyat (blood money), remnants of the Stone Ages which make murder a crime against the person, instead of the state itself, as in every decent country.

Given that Qisas and Diyat are not available for torture or sexual crimes, but rather only murder gives the powerful preparator incentive to just kill the victim after they have suffered brutally already, which is an extremely paradoxical and condemnable part of the law. This is why the criminal roams free with no reprimand for murder, almost always through intimidation of the deceased victim’s family or by playing to the greed of kin disconnected from the victim, as is almost always the case. The repugnant legacy of dictator Zia-ul-Haq continues to haunt Pakistan.

This caveat among other structural problems, makes the bill in practice only viable for people politically victimized to utilize when it's their turn in the government. Also missing are the reforms meant to accommodate the rehabilitation of those affected by custodial torture, so that they may receive support for their recovery, and in addition be eligible to receive monetary benefits for the wrongdoing committed by the state. There is no no regard in the legislation for those tortured who may have lost the ability to support themselves and their family’s livelihoods. This makes the highly awaited statute practically valid only for the politically victimized.

Pakistan’s constitution has prohibited the use of torture for extracting confessions under Article 14. However, that remains the only mention of torture in the constitution. Furthermore, the Pakistan Penal Code, Qanun-e-Shahadat Order, and the Code of Criminal Procedure also maintain brief mentions of laws which may be interpreted to deter torture. These mentions remain vague however, such as PPC Section 355, which claims that “assault or criminal force with intent to dishonor person, otherwise than on grave provocation” which is punishable with a prison term that may extend to 2 years, a fine, or both.

The new Act has been enacted at a federal level, so it extends to all of Pakistan. Within the Act, custody defines all places where a person is denied their liberty by a public office or an officer. Thus, it effectively applies to search, arrest and during other seizure procedures as well, while torture and degrading treatment are defined as the standard.

Custodial death includes death not only within custody, but death anywhere which can be attributed directly or indirectly to harm caused by the office in question. Rape includes all sexual abuse done by an officer taking advantage of their position to do this. The interpretation of wording thus makes the act far-reaching.

This was a much-needed statute, as torture is not seen as a major issue at large in Pakistani culture. Rather, torture is often glorified as a quick, and “effective” way to interrogate and punish wrongdoers. As showcased in news reports of police brutality from the United States for example, this is a problem even the first world suffers from to a large degree

This exists even though torture fails in all its purposes as a tool of interrogation, as those being tortured will almost always say whatever pleases the officer to stop the torture. Torture is not only physical but also a tool of psychological torment; each complementing the other.

Even torture methods thought to be more “passive” such as solitary confinement and sleep deprivation are not only still extremely harmful to victims in long run, but also still produce false confessions and information which also only serves to hamper appropriate investigations.

Apart from physical injuries and disabilities, victims may also suffer serious mental disorders such as PTSD, and depression among many other severe conditions. Victims may also suffer a loss of memory, and not even remember their own names and homes, as well as lose other skills and functions, in many cases rendering them unable to support their families and their livelihoods.

The harm to the torturers themselves is also understated. Those in power that use torture do not have to be involved in the process of torture itself, rather just give orders. Those who are tasked to carry out the torture will often find themselves suffering from long-lasting psychological harm.

A fairly common misconception is that only high-profile criminals suffer custodial torture. This is factually incorrect. According to various human rights organizations, all sorts of people, whether hardened criminal, petty thiefs, protestors, or just someone caught in the crossfire – have been victimized through custodial torture.

The ubiquity of torture in our public life as a nation can be evidenced through the frequent political victimization of the opposition by the given government of the day, and the clown show that the whole country witnesses throughout every party’s term. The act of using law enforcement agencies as personal thugs fundamentally undermines the democratic process within the country, which can perhaps be seen as the main catalyst for this act.

The problem with extant legislation were blatantly obvious; the law was so blurry and complicated in its nature, that applying it appropriately meant filing a First Information Report (FIR) for custodial torture was unnecessarily complicated, and in-ground realities made it near impossible for the poor and underprivileged class to file. This meant that the officer that had committed torture would face no real consequences. Thus, officers were able to torture, rape, murder and extract confessions under duress, without any viable protocol for the victim or their kin to take up against the officer in question.

Under the Act, the victim may directly report torture as a cognizable crime by the perpetrator; this means the police has the ability to jail the suspect, and can start an investigation against the suspect without awaiting a magistrate’s approval, such is the case for most serious crimes.

However, this is all theoretical as FIRs fall within the domain of the SHO of the station, who may as well deny a member of the general public their right. Further course of action for such persons is so complicated that it becomes nigh impossible to pursue. This is best put on display by the bizarre spectacle that was the inability of even Imran Khan to file an FIR against certain people for attempted murder, even though he had the Chief Minister of his preference in power.

Moreover, the fact remains that the perpetrator of the murder of any underprivileged person under custody is still able to squeeze through the nets of the new legislation. This is facilitated through the mechanisms of Qisas (forgiveness) or Diyat (blood money), remnants of the Stone Ages which make murder a crime against the person, instead of the state itself, as in every decent country.

Given that Qisas and Diyat are not available for torture or sexual crimes, but rather only murder gives the powerful preparator incentive to just kill the victim after they have suffered brutally already, which is an extremely paradoxical and condemnable part of the law. This is why the criminal roams free with no reprimand for murder, almost always through intimidation of the deceased victim’s family or by playing to the greed of kin disconnected from the victim, as is almost always the case. The repugnant legacy of dictator Zia-ul-Haq continues to haunt Pakistan.

This caveat among other structural problems, makes the bill in practice only viable for people politically victimized to utilize when it's their turn in the government. Also missing are the reforms meant to accommodate the rehabilitation of those affected by custodial torture, so that they may receive support for their recovery, and in addition be eligible to receive monetary benefits for the wrongdoing committed by the state. There is no no regard in the legislation for those tortured who may have lost the ability to support themselves and their family’s livelihoods. This makes the highly awaited statute practically valid only for the politically victimized.