Why reinvent the wheel in the form of a charter when you already have a Constitution? Why not bring the charter issue to Parliament as well, and why would the charter be respected when the Constitution isn’t?

The question should embarrass anyone doing their political engagement from behind a table at a press conference rather than on the floor of Parliament with the Constitution firmly in their grasp (literally and metaphorically). The absurdity and hollowness of the idea that an economic charter may be a silver bullet which splits Pakistan’s many gordian knots with cinematic style worthy of a Tom Cruise movie is to be found in Tahir Ashrafi’s nonsensical call for a “charter of Pakistan.” An economic charter is sitting like an imaginary treasure at the end of a slippery slope along which we’re moving, an appropriate reward for taking a smokescreen to its logical conclusion.

Mustafa Bajwa’s point that an economic charter is a “truck ki batti” or a red herring is well taken. Nevertheless, the possibilities for an economic charter (how it may be created, what its substance would be, and what we would do with it) are many and varied. That is exactly why it has become a persistent part of economic and policy discourse in Pakistan and refuses to go away, despite having made no real contribution towards Pakistan’s intellectual or policy landscape.

Do useless or irrelevant ideas persist? Of course. But it does warrant some investigation as to whether this particular idea is serving some function. I suspect that it persists as a blank screen or catch-all term on which people can project their imagination of a better Pakistan or at least a different Pakistan, and that can be a powerful instrument of discourse if not political settlement and economic policy making. As a vehicle in speculative imagination, it may very well be useful.

So there may be not one economic charter, but a plurality of charters. Some of them might indeed be red herrings or even completely delusional. Others might serve as vehicles for discussion and debate – and that can’t be a bad thing for a social order in need of remaking itself. And it really does need to remake itself because it is not prospering.

We must commit to processes which helps us practice and improve our cooperation over long time horizons.

In fact, besides the blank screen offered by politicians for people to project their visions on, at least three different publicly articulated and shared versions of an economic charter exist: the Pakistan Business Council’s, Dr. Hafiz Pasha’s, and the one most recently put forward by the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics.

In a country with a democracy deficit, the existence of three different versions of a charter coming from three very different sources - a private sector business group, a public sector think tank, and one published by a German non-profit organization - is most welcome.

My own view is that as we think about cooperating with each other, we should not just think of arriving at an agreement, but of long run processes. As the work of sociologist and philosopher Prof. Richard Sennett suggests, cooperation is a skill and a craft which can be practiced and improved (Sennett 2012). We must commit to processes which helps us practice and improve our cooperation over long time horizons.

Individuals may be dead in the long run, but societies and economies as a whole can continue to live in pain. And the larger ambition ought not to be to only thrive as individuals (the prosperity and liberty of the individual is key), but also to thrive as a collective. To that end, we might want to consider taking a page out of Keynes’s The End of Laissez Faire. Published in 1926 as a pamphlet, it articulated Keynes’s views at the end of an age of liberalism and how the world might move forward from that point. We might once again be at a similar juncture, hoping to give birth to something better after having witnessed the terrible failings and strains of neoliberalism.

In the conclusion to the essay, Keynes wrote:

“For my part, I think that Capitalism, wisely managed, can probably be made more efficient for attaining economic ends than any alternative system yet in sight, but that in itself it is in many ways extremely objectionable. Our problem is to work out a social organisation which shall be as efficient as possible without offending our notions of a satisfactory way of life. … We need by an effort of the mind to elucidate our own feelings. At present our sympathy and our judgement are liable to be on different sides, which is a painful and paralysing state of mind. … We need a new set of convictions which spring naturally from a candid examination of our own inner feelings in relation to the outside facts.”

Now, our conditions in Pakistan are those of material poverty and a vulnerable political economy exposed to war, disease and environmental catastrophe. The state preys on the weak and the country’s sovereignty lies in tatters, the power of the government of Pakistan to issue the national currency having been surrendered in exchange for IMF money.

While those are our outside facts, our inner feelings are of fear and hurt and anger and grief and insecurity.

The question then is, what new set of convictions will arise from a candid self-examination and how? Let us leave aside the “what” for now and focus on the “how.”

Remember: long run processes. Do we possess the means of candid self-examination? A big problem Pakistan faces is that the means through which we could conduct any candid examination as a society – our institutions of cultural self-expression and reflection – are all eroded.

Parliament and the Constitution are major casualties but certainly not the only ones.

What is the state of our public universities and public libraries? What is the state of our music? Is Coke Studio to be the artistic means of our self-reflection and self-examination? What is the state of cinema? What candid examination of ourselves do we hope to achieve while a commercial hit like Maula Jatt plays freely while a creative hit like Joyland remains banned in Punjab?

This state of affairs partly explains why we have latched onto the idea of an economic charter; we have done so out of desperate hope that it might be a vehicle of self-examination and reflection for us. (This point about institutions of reflection arose in a conversation with my teacher Prof. Khalid Mir, to whom I am grateful for his friendship and everything he has taught me.)

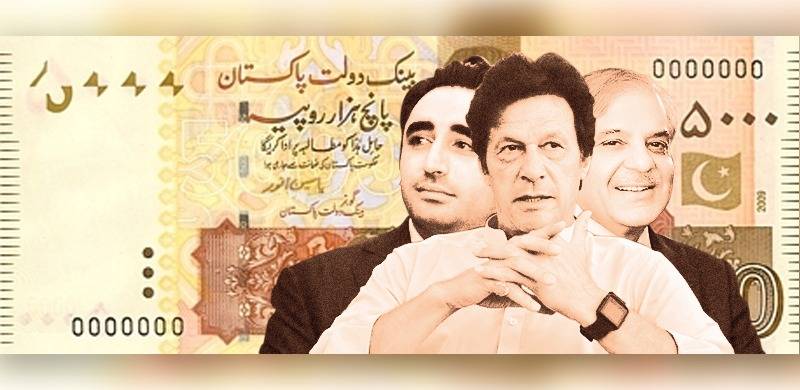

What’s more, our fragile social order with its eroding and crumbling institutions must contend with economic pressures. No social contract is going to survive hyperinflation undermining the rupee. As the value of the national currency erodes with increasing pace, at some point trust in the government’s guarantee of the value of currency, a guarantee stated on the front face of our SBP-issued banknotes, will start eroding with stunning pace. Thus, money as a social relationship between society and state will come under strain.

It is possible for the relationship to break down altogether. People are afraid of the country defaulting on its debts, and rightly so. But an irreparable rupture in the state-society relationship caused by the destruction of the rupee as a store of value (or even a means of exchange!) will be far more consequential and have implications entirely unimagined and unanticipated. So we are brought back both by force of argument and outside facts to square one: the urgency of committing to the democratic political process, to parliament, and to the Constitution.

”A healthy obsession, we could say, interrogates its own driving convictions” (Sennett 2008, 261). In this article I have tried to interrogate some of the driving convictions behind the obsession with an economic charter, which might be available to us as an aid to our self-reflection and self-examination as a society and country. But it is not a silver bullet.

It cannot replace the Constitution of Pakistan, the laws by which this country is governed, or ought to be governed, or our institutional architecture. We must be careful not to slide into a place where we obsessively linger on an economic charter and chain our expectations to it to distract ourselves from the real work, to use Prof. Sennett’s phrase, of making a life in common (Sennett 2008, 6).

References

Sennett, Richard. 2008. The Craftsman. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

Sennett, Richard. 2012. Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Cooperation. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.