The generals do their best to avoid discussing the events of 1971. Pervez Musharraf, Pakistan’s fourth military ruler, dismissed a question about the war, saying why should we care about something that happened such a long time ago.

In his farewell speech, General Qamar Javed Bajwa had a chance to salvage his reputation. Instead, he ended up pandering to the military establishment. Bajwa said the war was lost by the politicians and not the military. As he put it, Pakistan had 34,000 troops whereas India had 250,000 troops plus 200,000 armed rebels. The villains were the politicians since they had put the army in a horrible situation.

Yes, the Pakistani troops were severely outnumbered. They were also worn down by months of fighting a civil war. They did not have the full complement of their weapons. Most of the troops had been flown in from West Pakistan just a few months ago and did not know the language, culture or terrain.

But whose fault was that? The war was precipitated by the army’s decision to annul the general elections of 1970. The Awami League headed by Sheikh Mujib had won an absolute majority. General Yahya Khan, who was governing the country as president, army chief, and chief martial law administrator, had referred to Mujib as the future prime minister.

This elicited a strong reaction from Zulfikar Ali Bhutto whose Pakistan People’s Party had won the largest number of seats in West Pakistan. However, those were dwarfed by the number of seats that the Awami League had won. Bhutto suggested that Pakistan should have two prime ministers, one in the East and one in the West. He also threatened to break the legs of any of his elected party members who went to Dhaka to attend the opening session of the national assembly.

As expected, Mujib rejected the proposal. Bhutto ingratiated himself with a coterie of generals, all of whom were based in West Pakistan, and put pressure on Yahya to annul the elections. Instead of showing leadership and maturity, Yahya caved in and annulled the elections. On the date that the National Assembly was to meet, March 25, he launched Operation Searchlight to eliminate the leadership of the Awami League.

Two senior officers refused to carry out any military operation: Vice Admiral Ahsan and Lt.-Gen. Sahibzada Yaqub Khan. Lt-Gen. Tikka Khan took on the assignment, earning the moniker, Butcher of Bengal. In a couple of months, an uneasy calm descended on the province. Lt-Gen. Niazi was sent in to restore law and order.

Only the 14 Infantry Division was based in East Pakistan. Additional infantry divisions were rushed in from West Pakistan. India had imposed a no-fly zone for the Pakistanis so the troops were flown in via Sri Lanka. They came without the full complement of armour and artillery.

The Awami League created a militant wing to resist Operation Searchlight, plunging the province into a full-scale civil war. At some point, the army had alienated just about everyone who lived in East Pakistan. Refugees began to pour into the Indian province of West Bengal.

In his memoirs, East Pakistan: The Endgame, An Onlooker’s Journal: 1969-71, Brig. A.R. Siddiqui, who headed the Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR) from 1967-73, writes that the army began conducting murderous “sweeps” in which whole villages were wiped out. Niazi did not deny rapes were being carried out. Instead, he opined, “You cannot expect a man to live, fight, and die in East Pakistan and go to Jhelum for sex, would you?”

In the midst of bedlam, there appeared “a macabre joke,” a documentary from the government called “The Great Betrayal.” It was intended to show the evils being carried out by the “miscreants,” the army’s code word for rebels. But its footage of human skulls even irked Yahya’s sensitivities. He asked, “How could you differentiate between the two skulls – Bengalis and non-Bengalis? I am damned if I can tell one from the other.”

As the insurgency expanded, black protest flags replaced the national flag everywhere except in the cantonments. A furious general told Siddiqi, “No national army in the world has ever been subjected to such public humiliation.” But the general never paused to think why matters had come to such a sorry pass.

In November, Indian artillery began to pound the Pakistani forces in the East. To relieve pressure on the Eastern Garrison under Niazi, on the morning of December 3 Siddiqi was given a coded signal, “The balloon has gone up.” This meant that the PAF had launched sorties into India, Operation Chengiz Khan. When he asked Air Chief Marshal Rahim to justify the raids, the latter retorted, “Success is the biggest justification. My birds should be right over Agra by now, knocking the hell out of them.”

However, the PAF raids were anticipated by the IAF and dispersed their aircraft. The raids failed. Not only were the raids a failure, they gave Prime Minister Indira Gandhi the perfect excuse to order the Indian army into East Pakistan.

At GHQ in Rawalpindi, thinking they had won the war, the generals ordered a round of drinks “in an unbroken chain.” Imagining himself in a bar-room brawl, one gloated, “We will give the enemy a broken nose.” Even a teetotaler colonel who worked with Siddiqi “had a couple of stiff ones and downed them straight.”

Pakistan had long believed the defense of the East lay in the West. An army thrust was directed at Indian forces in Ramgarh, from where Delhi was going to be an easy target. It failed. Even Chamb in Indian-held Kashmir, which had been the prize of the 1965 war, was not taken. The much-awaited counter-offensive under Lt-Gen. Tikka, who had been moved back to the West, never took off.

The Chinese military attaché told Pakistanis, “The Indians are holding you on, waiting to get it over with in East Pakistan.”

As the denouement loomed, Lt-Gen. Gul Hassan, Chief of the General Staff, asked Siddiqi to do his “usual PR stuff.” When the latter said he was at a loss for words, he was scripted, “The army was out-numbered, out-gunned but not out-classed. Cut off from its main base, it did what could be expected from the best of armies.”

After the ill-advised PAF attack on IAF bases on December 3, Indian forces attacked East Pakistan with full fury. They also took on Pakistani positions in the West. Soon, the IAF was conducting daily raids on Karachi in broad daylight, mostly to terrorise the civilians.

In the East, Lt-Gen. Niazi had deployed the four divisions under his command all around the border, in “penny packets,” as Captain (later Brigadier) Salim Salik, his press relations officer at the time, writes in his book, Witness to Surrender. The Indians cut through the penny packets with ease, like a knife cutting through butter, and drove on to Dhaka.

In his memoirs, Lt-Gen. Gul Hassan, Chief of the General Staff, noted that one did not need to be a genius “to sense the impending catastrophe.” The army would be fighting the Indians in the front and the rebels on the flanks and in the rear. He said it would be hard to imagine “a more hopelessly disadvantaged position for opposing a superior foe.” And given the circumstances, when he was most needed, the supreme commander, Gen. Yahya Khan, had morphed into “a remote figure.” In the enveloping darkness, there was a complete “absence of direction” and no “cohesion in the nerve-center of the army.”

Niazi kept on expecting the US would come to his assistance from the South, since they had anchored the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, USS Enterprise, in the Bay of Bengal. He also expected the Chinese would come to his assistance from the North. When Indian paratroopers were raining in on Dhaka, he asked Salik to go out and see if they were “white from the south or yellow from the north.” Salik came back and told him, “They are brown just like us.” That’s when Niazi broke down in tears and told Salik that it was a bad day to be a general.

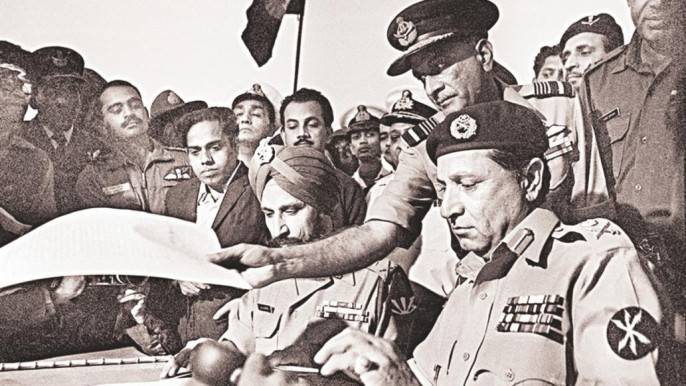

The Indians invaded Dhaka with fewer troops than Niazi had deployed in Dhaka and met with no resistance. In a ceremony watched by the world, he surrendered on December 16 to his Indian counterpart. The news shook the people in West Pakistan to the core. All along, they had been told they were winning the war. They thought it was incomprehensible that a Muslim army would ever surrender to a non-Muslim army.

When he had been asked what would happen if Indian forces entered Dhaka, Niazi had extended his chest and said that the Indians would have to drive a tank over it. He had toured the hospitals and told the frightened nurses that their honour would never be violated by Indian troops because he would shoot them before anyone touched them.

After the news of the surrender broke, Yahya came on Radio Pakistan to reassure a stunned nation that even though fighting had ceased on the eastern front due to “an arrangement between the local commanders,” the war with India would continue.

However, on the very next day, realising that his chances of surviving a full-scale war with India on the western front without US or Chinese support were slim, he agreed to a ceasefire. In the psychological build-up prior to the war, he had reduced his mission statement to just two words: “Crush India!”

Bumper stickers bearing this slogan were soon adorning thousands of cars in all major cities. An anti-India hysteria had set in. Seeking to now absolve himself from the opprobrium that he had brought onto Pakistan, he stated: “I have always maintained that wars solve no problems.” Of course, the victors in Dhaka knew otherwise.

Thus, East Pakistan had passed into the history books, and with it some argued the “Two-Nation Theory” that had led to Pakistan’s independence. It had exploded, like TNT.

Yet General Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan remained in the denial mode. In testimony before the Hamood-ur-Rehman War Commission, he justified all his actions and maintained that he did not consider Pakistan’s defeat “as a military debacle at all or surrender of forces in strictly military terms.” He asserted that “I can confidently say that no military historian would call this a military defeat. It was nothing but a treachery of the Indians.”

When asked about his reasons for calling a ceasefire on the western front, Yahya said he would have continued to fight across the West Pakistan borders had the UN General Assembly not passed a ceasefire resolution with an overwhelming majority. Like so many army officers, Yahya continued to live in denial to the bitter end.

In Blood Telegram, Gary Bass noted that Yahya was one of the few people that President Nixon liked, since he had provided him with the long-awaited opening to China. But Henry Kissinger had concluded that Yahya, despite his British affectation and bluster, was a moron. He felt that a point of no return had been reached and the East was going to secede even without an Indian invasion.

Kissinger knew that neither Yahya nor his generals had the intellect to understand why East Pakistan wanted to secede. They remained oblivious to the threat of an Indian invasion until the very end. Yahya kept telling Nixon that ‘normal life’ would soon return to East Pakistan.

In his 1979 memoir, The White House Years, Kissinger wrote: “[In early December], I told the NSC [National Security Council] meeting that there was no question of “saving” East Pakistan. Both Nixon and I had recognized for months that its independence was inevitable. Yahya was a bluff, direct soldier of limited imagination caught up after the convulsion of East Pakistan in events for which neither experience nor training prepared him. He made grievous mistakes… Sometimes the nerves of public figures snap. Incapable of abiding by events, they seek to force the pace and lose their balance. So it was that Yahya Khan, with less than 40,000 troops [in March], decided to establish military rule over the 75 million people of East Pakistan… What prompted Yahya to his reckless step on March 25 is not fully known… There was no likelihood that a small military force owing loyalty to the one wing of the country could indefinitely hold down… the other. Once indigenous Bengali support for a united Pakistan evaporated, the integrity of Pakistan was finished. An independent Bengali state was certain to emerge, even without Indian intervention…. [As the crisis worsened, Yahya and his generals] knew by now that their brutal suppression of East Pakistan beginning on March 25 had been in Talleyrand’s phrase, worse than a crime; it was a blunder.”

Gul Hassan concludes that the army lost the war due to its blunders.

In his retirement, General Bajwa should make it a point to read what has been written about the war by Pakistan’s own generals. It’s never too late to heed Santayana’s warning: “Those who don’t learn from history are condemned to repeat it.”

In his farewell speech, General Qamar Javed Bajwa had a chance to salvage his reputation. Instead, he ended up pandering to the military establishment. Bajwa said the war was lost by the politicians and not the military. As he put it, Pakistan had 34,000 troops whereas India had 250,000 troops plus 200,000 armed rebels. The villains were the politicians since they had put the army in a horrible situation.

Yes, the Pakistani troops were severely outnumbered. They were also worn down by months of fighting a civil war. They did not have the full complement of their weapons. Most of the troops had been flown in from West Pakistan just a few months ago and did not know the language, culture or terrain.

But whose fault was that? The war was precipitated by the army’s decision to annul the general elections of 1970. The Awami League headed by Sheikh Mujib had won an absolute majority. General Yahya Khan, who was governing the country as president, army chief, and chief martial law administrator, had referred to Mujib as the future prime minister.

This elicited a strong reaction from Zulfikar Ali Bhutto whose Pakistan People’s Party had won the largest number of seats in West Pakistan. However, those were dwarfed by the number of seats that the Awami League had won. Bhutto suggested that Pakistan should have two prime ministers, one in the East and one in the West. He also threatened to break the legs of any of his elected party members who went to Dhaka to attend the opening session of the national assembly.

As expected, Mujib rejected the proposal. Bhutto ingratiated himself with a coterie of generals, all of whom were based in West Pakistan, and put pressure on Yahya to annul the elections. Instead of showing leadership and maturity, Yahya caved in and annulled the elections. On the date that the National Assembly was to meet, March 25, he launched Operation Searchlight to eliminate the leadership of the Awami League.

Two senior officers refused to carry out any military operation: Vice Admiral Ahsan and Lt.-Gen. Sahibzada Yaqub Khan. Lt-Gen. Tikka Khan took on the assignment, earning the moniker, Butcher of Bengal. In a couple of months, an uneasy calm descended on the province. Lt-Gen. Niazi was sent in to restore law and order.

Only the 14 Infantry Division was based in East Pakistan. Additional infantry divisions were rushed in from West Pakistan. India had imposed a no-fly zone for the Pakistanis so the troops were flown in via Sri Lanka. They came without the full complement of armour and artillery.

The Awami League created a militant wing to resist Operation Searchlight, plunging the province into a full-scale civil war. At some point, the army had alienated just about everyone who lived in East Pakistan. Refugees began to pour into the Indian province of West Bengal.

In a ceremony watched by the world, he surrendered on December 16 to his Indian counterpart. The news shook the people in West Pakistan to the core. All along, they had been told they were winning the war. They thought it was incomprehensible that a Muslim army would ever surrender to a non-Muslim army.

In his memoirs, East Pakistan: The Endgame, An Onlooker’s Journal: 1969-71, Brig. A.R. Siddiqui, who headed the Inter-Services Public Relations (ISPR) from 1967-73, writes that the army began conducting murderous “sweeps” in which whole villages were wiped out. Niazi did not deny rapes were being carried out. Instead, he opined, “You cannot expect a man to live, fight, and die in East Pakistan and go to Jhelum for sex, would you?”

In the midst of bedlam, there appeared “a macabre joke,” a documentary from the government called “The Great Betrayal.” It was intended to show the evils being carried out by the “miscreants,” the army’s code word for rebels. But its footage of human skulls even irked Yahya’s sensitivities. He asked, “How could you differentiate between the two skulls – Bengalis and non-Bengalis? I am damned if I can tell one from the other.”

As the insurgency expanded, black protest flags replaced the national flag everywhere except in the cantonments. A furious general told Siddiqi, “No national army in the world has ever been subjected to such public humiliation.” But the general never paused to think why matters had come to such a sorry pass.

In November, Indian artillery began to pound the Pakistani forces in the East. To relieve pressure on the Eastern Garrison under Niazi, on the morning of December 3 Siddiqi was given a coded signal, “The balloon has gone up.” This meant that the PAF had launched sorties into India, Operation Chengiz Khan. When he asked Air Chief Marshal Rahim to justify the raids, the latter retorted, “Success is the biggest justification. My birds should be right over Agra by now, knocking the hell out of them.”

However, the PAF raids were anticipated by the IAF and dispersed their aircraft. The raids failed. Not only were the raids a failure, they gave Prime Minister Indira Gandhi the perfect excuse to order the Indian army into East Pakistan.

At GHQ in Rawalpindi, thinking they had won the war, the generals ordered a round of drinks “in an unbroken chain.” Imagining himself in a bar-room brawl, one gloated, “We will give the enemy a broken nose.” Even a teetotaler colonel who worked with Siddiqi “had a couple of stiff ones and downed them straight.”

Pakistan had long believed the defense of the East lay in the West. An army thrust was directed at Indian forces in Ramgarh, from where Delhi was going to be an easy target. It failed. Even Chamb in Indian-held Kashmir, which had been the prize of the 1965 war, was not taken. The much-awaited counter-offensive under Lt-Gen. Tikka, who had been moved back to the West, never took off.

The Chinese military attaché told Pakistanis, “The Indians are holding you on, waiting to get it over with in East Pakistan.”

As the denouement loomed, Lt-Gen. Gul Hassan, Chief of the General Staff, asked Siddiqi to do his “usual PR stuff.” When the latter said he was at a loss for words, he was scripted, “The army was out-numbered, out-gunned but not out-classed. Cut off from its main base, it did what could be expected from the best of armies.”

After the ill-advised PAF attack on IAF bases on December 3, Indian forces attacked East Pakistan with full fury. They also took on Pakistani positions in the West. Soon, the IAF was conducting daily raids on Karachi in broad daylight, mostly to terrorise the civilians.

In the East, Lt-Gen. Niazi had deployed the four divisions under his command all around the border, in “penny packets,” as Captain (later Brigadier) Salim Salik, his press relations officer at the time, writes in his book, Witness to Surrender. The Indians cut through the penny packets with ease, like a knife cutting through butter, and drove on to Dhaka.

In his memoirs, Lt-Gen. Gul Hassan, Chief of the General Staff, noted that one did not need to be a genius “to sense the impending catastrophe.” The army would be fighting the Indians in the front and the rebels on the flanks and in the rear. He said it would be hard to imagine “a more hopelessly disadvantaged position for opposing a superior foe.” And given the circumstances, when he was most needed, the supreme commander, Gen. Yahya Khan, had morphed into “a remote figure.” In the enveloping darkness, there was a complete “absence of direction” and no “cohesion in the nerve-center of the army.”

Niazi kept on expecting the US would come to his assistance from the South, since they had anchored the nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, USS Enterprise, in the Bay of Bengal. He also expected the Chinese would come to his assistance from the North. When Indian paratroopers were raining in on Dhaka, he asked Salik to go out and see if they were “white from the south or yellow from the north.” Salik came back and told him, “They are brown just like us.” That’s when Niazi broke down in tears and told Salik that it was a bad day to be a general.

The Indians invaded Dhaka with fewer troops than Niazi had deployed in Dhaka and met with no resistance. In a ceremony watched by the world, he surrendered on December 16 to his Indian counterpart. The news shook the people in West Pakistan to the core. All along, they had been told they were winning the war. They thought it was incomprehensible that a Muslim army would ever surrender to a non-Muslim army.

When he had been asked what would happen if Indian forces entered Dhaka, Niazi had extended his chest and said that the Indians would have to drive a tank over it. He had toured the hospitals and told the frightened nurses that their honour would never be violated by Indian troops because he would shoot them before anyone touched them.

After the news of the surrender broke, Yahya came on Radio Pakistan to reassure a stunned nation that even though fighting had ceased on the eastern front due to “an arrangement between the local commanders,” the war with India would continue.

Kissinger knew that neither Yahya nor his generals had the intellect to understand why East Pakistan wanted to secede. They remained oblivious to the threat of an Indian invasion until the very end. Yahya kept telling Nixon that ‘normal life’ would soon return to East Pakistan.

However, on the very next day, realising that his chances of surviving a full-scale war with India on the western front without US or Chinese support were slim, he agreed to a ceasefire. In the psychological build-up prior to the war, he had reduced his mission statement to just two words: “Crush India!”

Bumper stickers bearing this slogan were soon adorning thousands of cars in all major cities. An anti-India hysteria had set in. Seeking to now absolve himself from the opprobrium that he had brought onto Pakistan, he stated: “I have always maintained that wars solve no problems.” Of course, the victors in Dhaka knew otherwise.

Thus, East Pakistan had passed into the history books, and with it some argued the “Two-Nation Theory” that had led to Pakistan’s independence. It had exploded, like TNT.

Yet General Agha Muhammad Yahya Khan remained in the denial mode. In testimony before the Hamood-ur-Rehman War Commission, he justified all his actions and maintained that he did not consider Pakistan’s defeat “as a military debacle at all or surrender of forces in strictly military terms.” He asserted that “I can confidently say that no military historian would call this a military defeat. It was nothing but a treachery of the Indians.”

When asked about his reasons for calling a ceasefire on the western front, Yahya said he would have continued to fight across the West Pakistan borders had the UN General Assembly not passed a ceasefire resolution with an overwhelming majority. Like so many army officers, Yahya continued to live in denial to the bitter end.

In Blood Telegram, Gary Bass noted that Yahya was one of the few people that President Nixon liked, since he had provided him with the long-awaited opening to China. But Henry Kissinger had concluded that Yahya, despite his British affectation and bluster, was a moron. He felt that a point of no return had been reached and the East was going to secede even without an Indian invasion.

Kissinger knew that neither Yahya nor his generals had the intellect to understand why East Pakistan wanted to secede. They remained oblivious to the threat of an Indian invasion until the very end. Yahya kept telling Nixon that ‘normal life’ would soon return to East Pakistan.

In his 1979 memoir, The White House Years, Kissinger wrote: “[In early December], I told the NSC [National Security Council] meeting that there was no question of “saving” East Pakistan. Both Nixon and I had recognized for months that its independence was inevitable. Yahya was a bluff, direct soldier of limited imagination caught up after the convulsion of East Pakistan in events for which neither experience nor training prepared him. He made grievous mistakes… Sometimes the nerves of public figures snap. Incapable of abiding by events, they seek to force the pace and lose their balance. So it was that Yahya Khan, with less than 40,000 troops [in March], decided to establish military rule over the 75 million people of East Pakistan… What prompted Yahya to his reckless step on March 25 is not fully known… There was no likelihood that a small military force owing loyalty to the one wing of the country could indefinitely hold down… the other. Once indigenous Bengali support for a united Pakistan evaporated, the integrity of Pakistan was finished. An independent Bengali state was certain to emerge, even without Indian intervention…. [As the crisis worsened, Yahya and his generals] knew by now that their brutal suppression of East Pakistan beginning on March 25 had been in Talleyrand’s phrase, worse than a crime; it was a blunder.”

Gul Hassan concludes that the army lost the war due to its blunders.

In his retirement, General Bajwa should make it a point to read what has been written about the war by Pakistan’s own generals. It’s never too late to heed Santayana’s warning: “Those who don’t learn from history are condemned to repeat it.”