Honour killings regretfully remain a fact all over the world. This is the case not only in third-world countries, but also in some first-world communities. Pakistan is heavily affected by such ‘honour’-motivated murders.

The reasons for perceived dishonour to the family, which may justify murder, include being victims of sexual assault such as rape, facing accusations of ‘illicit affairs,’ giving birth to a female child, wearing ‘revealing’ clothing, wanting to marry a person of their choice, pursuing education or employment, seeking a divorce, or claiming a part of an inheritance, among other reasons.

This isn’t surprising given that in the most populous province of Punjab, about 80% of women suffer domestic abuse, with the police not considering it a serious offence and instead promoting ‘reconciliation.’ An extremely patriarchal culture exists that denotes complete male autonomy over a woman’s body, which in turn ties it to the man’s dignity.

In Pakistan, honour killings have been able to be committed scot-free with almost all perpetrators escaping any punishment. It is unsurprising that Pakistan historically had the highest per capita reported and estimated number of honour killings; known locally as Karo-Kari (literally, "blackened man and woman"). Every year, one-fifth of all honour killings in the world occur in Pakistan. Men are also not spared according to statistics, although there are far more female victims.

Pakistani law provides an escape route to the most dangerous criminals who are a threat to society; in the form of "compoundable offences." According to the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC) provisions dealing with sentencing: for murder (Section 302) and attempt to murder (Section 324), any sentence can be avoided. This mechanism works on the concept of Qisas and Diyat under sections 309 and 310 of the PPC, respectively. These are Shariah concepts introduced as a result of hardline Islamist politics used during General Zia-ul Haq's dictatorship, though the ordinance was formally introduced after his death.

Simply put, Qisas means retribution, and a court may decide on a prison sentence or execution as the equal punishment for the crime of intentional murder (as is the case in honour killings). Diyat refers to ‘blood money,’ which is monetary compensation that legal heirs of a victim may receive as a compromise with the offender. Qisas may be completely waived by the victim’s family. This means a murderer may be able to walk free by waiving Qisas, or by offering money. No case needs to be made about how this mechanism can be freely abused by people of power and influence.

Since almost all honour killings are usually committed by a family member of the victim, this would almost ‘automatically’ entail the murderers being easily forgiven by Qisas and punishment being waived – as both the murderer and the victim would be part of the same family.

It made no difference in the rare case where the victims' families were not complicit in the honour killing, because communal pressure would prevail for families in accordance with local customs and culture. Often the influence of the community leader(s) would bail out the killers.

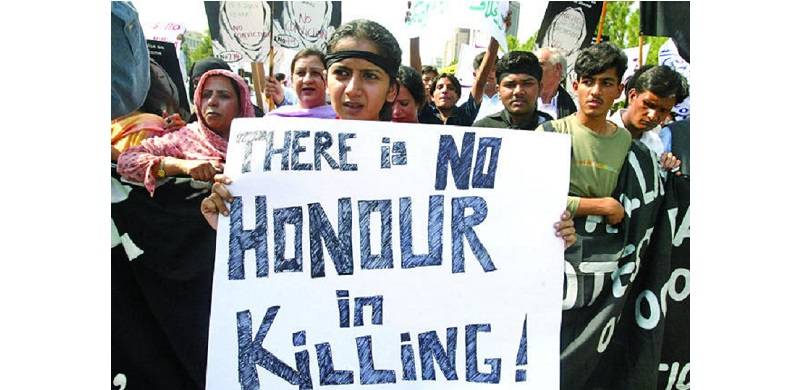

In 2016, there was a surge in activism against honour killings in Pakistan as a result of the recent murder of Qandeel Baloch, a ‘bold’ model representing freedom of female expression in Pakistan. As a result, Section 311 of the Penal Code was amended in 2016 wherein the court may punish an offender against whom the right of qisas has been waived or compounded with death or imprisonment. However, loopholes remain.

In the case of Qandeel Baloch, her brother murdered her, for the sake of ‘honour,’ and boldly admitted it in a press conference, while further forensics proved the fact. The murderer of Qandeel Baloch was sentenced to life in prison by the Trial Court, under Section 311. However, in appeal, the murderer retracted the statement that the murder was committed in the name of honour.

In February 2022, the High Court noted the trial court had not gone through the correct procedures for procuring a valid confession as laid down in the Azeem Khan and Ahmed Omer cases when the confession that the murder was committed for honour was recorded. Thus, it was held to be just a murder and not an honour killing, and therefore Qisas could be waived. Qandeel’s parents also changed their minds and forgave their son.

Consequently, a proven murderer walked free, despite legislation. Murders in the name of honour can continue unabated, confessions for reasons other than honour allow murderers to run freely on streets that are already dangerous for women. The principles of Qisas and Diyat have allowed countless repeat offenders to go unpunished.

Simply put: if the court chooses to disregard violations of human rights by the police or judiciary itself today (which often coerces a false confession), might victims of such brutality avoid court proceedings, since they would not know how the court will interpret the legislation tomorrow? Or does the court sanction such tactics in the future?

In fact, it is the legislators and the government who are to blame for allowing a murderer to be forgiven. These acts are not a crime against an individual but against the state, and the state must take it up to protect its people.

Therefore, one is forced to hold responsible the often-corrupt lawmakers elected to the provincial and national assemblies, who decide to turn a blind eye to this law – allowing murderers to run free, as they refuse to do anything that may sour their public image among hardline conservatives.

Furthermore, we must look at the failure of the Pakistani government itself regarding all kinds of human rights, especially relating to the abuse of Qisas and Diyat, which every government since 1990 has refused to examine.

Let us not forget that this is all happening while the President can offer ordinances to curb the fundamental right of expression, so that criticism against the state is minimal in the form of an ordinance amending the Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act (nullified by the Supreme Court in April 2022). But the same type of presidential intervention cannot be done for a law that allows murderers to run freely and often commit further offences.

This all has its roots in Islamist politics, which have become a praxis ever since their liberal usage by Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in the 1970s. Abolishing a piece of what is seen as Shariah, that is not properly applied in its current state for a modern country of 220 million people, might still be used by the opposition against the government to sour the public's opinion. The leader cannot even speak on such subjects, so as not to lose political influence in the extremely ultra-conservative and tribal areas, where honour killings occur the most.

Even when a government can touch this issue, it is not possible to change these practices through mere amendments to sentencing law. Larger reforms relating to the proper education of human rights and increasing the reach of legal administration are desperately needed. But this matter does not seem to be a priority.

The reasons for perceived dishonour to the family, which may justify murder, include being victims of sexual assault such as rape, facing accusations of ‘illicit affairs,’ giving birth to a female child, wearing ‘revealing’ clothing, wanting to marry a person of their choice, pursuing education or employment, seeking a divorce, or claiming a part of an inheritance, among other reasons.

This isn’t surprising given that in the most populous province of Punjab, about 80% of women suffer domestic abuse, with the police not considering it a serious offence and instead promoting ‘reconciliation.’ An extremely patriarchal culture exists that denotes complete male autonomy over a woman’s body, which in turn ties it to the man’s dignity.

In Pakistan, honour killings have been able to be committed scot-free with almost all perpetrators escaping any punishment. It is unsurprising that Pakistan historically had the highest per capita reported and estimated number of honour killings; known locally as Karo-Kari (literally, "blackened man and woman"). Every year, one-fifth of all honour killings in the world occur in Pakistan. Men are also not spared according to statistics, although there are far more female victims.

Pakistani law provides an escape route to the most dangerous criminals who are a threat to society; in the form of "compoundable offences." According to the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC) provisions dealing with sentencing: for murder (Section 302) and attempt to murder (Section 324), any sentence can be avoided. This mechanism works on the concept of Qisas and Diyat under sections 309 and 310 of the PPC, respectively. These are Shariah concepts introduced as a result of hardline Islamist politics used during General Zia-ul Haq's dictatorship, though the ordinance was formally introduced after his death.

Simply put, Qisas means retribution, and a court may decide on a prison sentence or execution as the equal punishment for the crime of intentional murder (as is the case in honour killings). Diyat refers to ‘blood money,’ which is monetary compensation that legal heirs of a victim may receive as a compromise with the offender. Qisas may be completely waived by the victim’s family. This means a murderer may be able to walk free by waiving Qisas, or by offering money. No case needs to be made about how this mechanism can be freely abused by people of power and influence.

Since almost all honour killings are usually committed by a family member of the victim, this would almost ‘automatically’ entail the murderers being easily forgiven by Qisas and punishment being waived – as both the murderer and the victim would be part of the same family.

It made no difference in the rare case where the victims' families were not complicit in the honour killing, because communal pressure would prevail for families in accordance with local customs and culture. Often the influence of the community leader(s) would bail out the killers.

In 2016, there was a surge in activism against honour killings in Pakistan as a result of the recent murder of Qandeel Baloch, a ‘bold’ model representing freedom of female expression in Pakistan. As a result, Section 311 of the Penal Code was amended in 2016 wherein the court may punish an offender against whom the right of qisas has been waived or compounded with death or imprisonment. However, loopholes remain.

In the case of Qandeel Baloch, her brother murdered her, for the sake of ‘honour,’ and boldly admitted it in a press conference, while further forensics proved the fact. The murderer of Qandeel Baloch was sentenced to life in prison by the Trial Court, under Section 311. However, in appeal, the murderer retracted the statement that the murder was committed in the name of honour.

In February 2022, the High Court noted the trial court had not gone through the correct procedures for procuring a valid confession as laid down in the Azeem Khan and Ahmed Omer cases when the confession that the murder was committed for honour was recorded. Thus, it was held to be just a murder and not an honour killing, and therefore Qisas could be waived. Qandeel’s parents also changed their minds and forgave their son.

Consequently, a proven murderer walked free, despite legislation. Murders in the name of honour can continue unabated, confessions for reasons other than honour allow murderers to run freely on streets that are already dangerous for women. The principles of Qisas and Diyat have allowed countless repeat offenders to go unpunished.

Simply put: if the court chooses to disregard violations of human rights by the police or judiciary itself today (which often coerces a false confession), might victims of such brutality avoid court proceedings, since they would not know how the court will interpret the legislation tomorrow? Or does the court sanction such tactics in the future?

In fact, it is the legislators and the government who are to blame for allowing a murderer to be forgiven. These acts are not a crime against an individual but against the state, and the state must take it up to protect its people.

Therefore, one is forced to hold responsible the often-corrupt lawmakers elected to the provincial and national assemblies, who decide to turn a blind eye to this law – allowing murderers to run free, as they refuse to do anything that may sour their public image among hardline conservatives.

Furthermore, we must look at the failure of the Pakistani government itself regarding all kinds of human rights, especially relating to the abuse of Qisas and Diyat, which every government since 1990 has refused to examine.

Let us not forget that this is all happening while the President can offer ordinances to curb the fundamental right of expression, so that criticism against the state is minimal in the form of an ordinance amending the Pakistan Electronic Crimes Act (nullified by the Supreme Court in April 2022). But the same type of presidential intervention cannot be done for a law that allows murderers to run freely and often commit further offences.

This all has its roots in Islamist politics, which have become a praxis ever since their liberal usage by Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in the 1970s. Abolishing a piece of what is seen as Shariah, that is not properly applied in its current state for a modern country of 220 million people, might still be used by the opposition against the government to sour the public's opinion. The leader cannot even speak on such subjects, so as not to lose political influence in the extremely ultra-conservative and tribal areas, where honour killings occur the most.

Even when a government can touch this issue, it is not possible to change these practices through mere amendments to sentencing law. Larger reforms relating to the proper education of human rights and increasing the reach of legal administration are desperately needed. But this matter does not seem to be a priority.