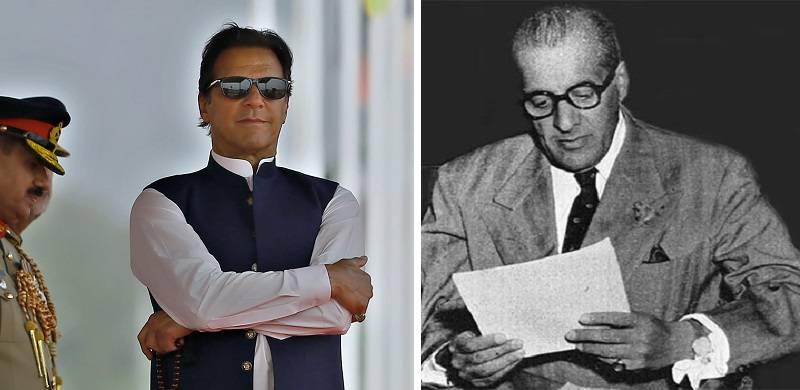

Mr. Imran Khan welcomes the Judiciary’s decision on Article 63-A as it positively impacts his politics, especially in Punjab. Political and legal discourse is increasingly revolving around conspiracies and political intrigue while constitutional crises aren’t given due importance. Being an esteemed constitutional lawyer, the Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah founded this nation on democratic principles. Since “Western democracy” is a part of political discourse, I would like to highlight here that the constitutional history of the Commonwealth can raise serious questions about Mr. Khan’s constitutional breaches, as they are reminiscent of another autocratic but dapper Governor-General from Lahore, Punjab (with a Pathan background), who happens to be the architect of Punjabi political domination and the reason behind Pakistan’s departure from democracy in 1954.

Historical records indicate that Mr. Khan is chillingly similar to the Punjabi Governor-General who was responsible for the first constitutional crisis in 1954. Unfortunately, the torrential decades of undemocratic rule have shrouded the comparison that is more historically relevant in today’s times than the centuries-old tale of betrayal of Mir Jafar. With Pakistan on the cusp of achieving democracy, one must relive the events that led to its halt on the day of 24 October 1954.

The mirror image of 10 April 2022 – 24 October 1954 (the First Constitutional Crisis & the First Military Coup)

On this day, the Punjabi G-G dismissed the Bengali-dominated First Constituent Assembly and promised fresh elections – which is exactly what Mr. Khan and his followers, continue to vociferously demand. The narrative of “fresh elections” was employed by him after the dissolution of the parliament, resulting in a political crisis amidst an ongoing economic crisis. The introduction of a constitutional crisis into the mix of crises afforded the military with a convenient entry into the political arena for the very first time in 1954. The Punjabi G-G was responsible for extending this invitation to the military multiple times. Just like Mr. Khan is calling out to the Mir Jafars of today, the Punjabi G-G had called out to Gen. Iskander Mirza in 1954, the descendant of Mir Jafar of folklore, only to disturb the institutional balance of power for almost seven decades. Is Mr. Khan unaware of the historical significance of demanding “fresh elections” after dissolving the National Assembly? As an expert on “Western democracy,” one would hope he is not entirely unaware. Yet, he continues to criticize the military for its adoption of an apolitical stance, in addition to threatening the country with fragmentation. If his supporters believe that he is naïve enough to be unaware, he should be made aware by educated segments that he is responsible for openly spreading undemocratic norms in society by following the autocratic legacy of Governor-General Malik Ghulam Muhammad.

Mr. Khan’s misuse of 63-A matches the G-G’s manipulation of the Damocles’ sword of disqualification, and that of defection – both of which dangled above the heads of politicians in the form of Public and Representative Office Disqualification Act (PRODA). The PM who enjoyed the VOC of the parliament, Sir Khwaja Nazimuddin, was unceremoniously dismissed on the basis of “conspiracies,” along with the entire assembly. The G-G claimed that the entire assembly ceased to be representative of the people of Pakistan as all of them were “ghaddars” involved in conspiracies against the state. On 10 April, Mr. Khan had full intentions of using this very claim to wipe off the parliament if only he had the judicial sanction to do so. His actions were clearly intended to generate a political crisis through the abuse of constitutional powers.

In terms of regard for the Constitution, the G-G axed the Constitution based on the democratic structure formulated by the Quaid. Instead, he helped develop the First Constitution of 1956 in which the title of Governor-General was morphed into the President, carrying the same dictatorial power structure that the Quaid was against. This role involved control over a) Governors – who can dismiss ministries and prevent oath-takings of CMs, and b) the Judiciary – that can accept the whimsical dissolution of assemblies on the basis of conspiracies. The makers of this first Constitution had their own version of Riyasat-e-Madinah; they called it the “Islamic Republic of Pakistan” and it was certainly not representative of the Quaid’s vision. Mr. Khan’s vision of the theocratic state of seventh century Madinah, based on the Presidential system of governance and deep regard for “rule of law”, bears striking similarity with the First Constitution of 1956. Moreover, the current power struggle in Punjab has proven Mr. Khan’s heightened potential for abuse of constitutional powers vested within the powerful roles he wishes to instate if given the chance to govern.

Moreover, opportunism is clearly visible in the common method employed by both, Mr. Khan and the G-G, in their respective pursuits of political power. Both entered politics when the arena was facing a political vacuum and democracy had eroded. After the passing away of the Quaid and Liaquat Ali Khan, the nation faced a political and an economic crisis simultaneously, much like the one today. Seven decades ago, the “anti-corruption narrative” was manufactured to generate polarization and societal divide. Mr. Khan has successfully brought our society to the same polarizing point again in 2022, where his party followers vehemently label supporters of all other parties as ghaddars.

Their communication strategy is almost identical. Rising to the occasion, both emerged as empowered Punjabis from the English-speaking upper-class of Lahore, claiming that the proof of their altruism is the foreign billionaire background that they left behind for the people of Pakistan. They displayed financial integrity which at that time was considered rare but welcomed as a virtue of the Quaid. The G-G claimed that he wanted to help build a “newer, stronger Pakistan” or Naya Pakistan for the post-Partition youth that grappled with limited employment opportunities in the midst of an economic crisis. With major plausible security threats, the military warranted high defence budgets. Poor economy in the presence of high defence expenditures made corrupt politicians a convenient excuse to deflect the public discourse from core economic and political issues.

Till date, Pakistan is globally known for allocating high defence budgets, yet PTI supporters are convinced that corruption is the sole reason behind economic crises. The disillusioned and uninformed youth of today with limited economic resources solely holds corrupt politicians responsible for their poor conditions, as was done in 1954. In the backdrop of such a strongly established anti-corruption narrative, financial integrity is certainly viewed as a highly attractive quality. It is especially an easy one to emulate for a power-hungry man – one who isn’t drawn to money, as claimed by both – the G-G in 1954, and Mr. Khan in 2022. Both used the Quaid’s virtues of integrity to further their politics, but eventually abused constitutional powers while governing disillusioned populaces. Clearly, world history and Pakistani history, both, are no strangers to power-hungry autocrats with clean banking records.

For the Quaid, “a constitutional lawyer of considerable perspicacity,” constitutional breaches were in fact, an anathema, as they clearly establish the desire for autocratic power in the perpetrator. Crimes against the Constitution that threaten the very existence of the nation must not be viewed lightly by the youth of a democratic nation. Both, Mr. Khan and the G-G, have inserted constitutional crises into an already prevailing mix of political and economic crises – connivingly designed to destabilize the nation. Basically, Mr. Khan tried to recreate the day of 24 October 1954, proof of which lies in the Mir Jafar reference. If Mr. Khan possessed the knowledge of and acted as per the strategy adopted by the G-G in 1954, he can be tried for sedition for attempting to conspire against the state using history as a reference.

The Presidential system the state of Madinah was instated by a Militablishment-backed and run government of Gen. Ayub Khan and Gen. Iskander Mirza in 1956. With Mir Jafar references, maybe Mr. Khan wants to take us back to that pre-democratic era. Moreover, Pakistan has been in a state of “incomplete Constitution-making” since its inception because the Constitution that the Quaid desired could not be actualized in its entirety. It is important to realise that Pakistan was formed on democratic norms instilled in us by the Quaid and questioning those very norms is tantamount to questioning the existence of Pakistan, along with questioning the vision of the Quaid for a democratically elected Muslim population of the Subcontinent.

Mr. Khan’s refusal to join the democratic setup and consistent denials of entering the political arena despite calls by the Government are indicative of the disruptive politics he wishes to engage in – the old “All or None” principle adopted by extremists with autocratic tendencies. While there are challenges, there are wins, too. The state institutions and the Judiciary neutralized the impact of Mr. Khan’s constitutional breaches on the institutional balance of power. In formulating his defense, Mr. Khan targeted the apt roles of institutions and the judiciary that followed historic judgments. He hoodwinked his supporters to criticise the applaudable role of the Judiciary in successfully burying the doctrine of necessity. Finally, the erstwhile Militablishment officially metamorphosed into the military after recognising its stance as apolitical, putting rest to seven decades of torment at the hands of hybrid regimes and ushering in the possibility of a democratic era. Unfortunately, the crowds around Mr. Khan who heard his references to Mir Jafar are uninformed and unaware of Mr. Khan’s viciousness.

I held detailed personalised interviews with 86 adult (25-35 years of age) PTI supporters, male and female (1:1 ratio) all from educated segments of society. They were asked to take a survey on General Knowledge.

Most of the respondents did not know that the VONC is a part of all democracies; hence their undemocratic opinions are pardonable, but Mr. Khan’s rejection of this democratic process, being an expert on “Western democracy,” is tantamount to spreading undemocratic norms in society. #Emergency (Twitter, 9 April)

Most of the respondents were unaware of the legal concept of the doctrine of necessity; hence, the Judiciary’s legal maturity was poorly understood by them. Mr. Khan made this segment of society question the democratic norm of “institutional neutrality” along with the misuse of religion as a tactic (neutral sirf janwar hota hai) – this is tantamount to spreading undemocratic norms in society. #SurrenderBajwa (Twitter, 10 April)

All of the respondents selected the “anti-corruption narrative” as being their main reason for supporting him – a narrative being employed since decades to promote societal divide in a highly political society.

Sadly, all of them said that if Mr. Khan were to leave PTI, they will cease to extend their support to PTI. This is reflective of an autocratic power-sharing model where the entire party structure is dependent on one individual’s hero worship.

Mr. Khan has clearly earned an audience through half-truths and selective narratives and clearly does not believe in the democratic power-sharing model. The results of this survey are proof to his indoctrination of a societal segment.

While Mr. Khan claims that he follows the virtues of the Quaid, he acts in a manner that is clearly quite contrary to it. Could this be the case of political domination by a power-hungry, English-speaking, tall and dapper, Punjabi (with a Pathan background) from the upper class of Lahore? History shows that it is possible and sometimes chillingly similar, as highlighted by Dr. Yaqoob Khan Bangash.

Dr. Paula Newberg starts her book Judging the State (1995) with a quote from Ghalib: “The beginning of a thing is a mirror of its end.” An undemocratic reign has been put to an end in coincidentally the same sequence of events during a night of the holiest month of the Muslim calendar. I hope provincial and political divides cease to plague us and we come together to participate in a democratic process where we observe the virtues and principles of the Quaid rather than those that commit constitutional breaches that are an anathema to the very foundation of this nation. We deserve an end to the “political horizon charred by extended periods of rule by a predominantly Punjabi military and bureaucracy” as written by Dr. Ayesha Jalal. For that, it is essential to formulate our political choices based on relevant facts rather than engaging in political discourse revolving around conspiracies.

Even the G-G’s reign in 1954 was known as “saazishon ka daur.” I pray that we enter “Naya Daur” instead. For a nation formed on the basis of the constitutional rights of Muslims in the Subcontinent, it is essential to further the democratic principles that are enshrined in its very foundation.

Historical records indicate that Mr. Khan is chillingly similar to the Punjabi Governor-General who was responsible for the first constitutional crisis in 1954. Unfortunately, the torrential decades of undemocratic rule have shrouded the comparison that is more historically relevant in today’s times than the centuries-old tale of betrayal of Mir Jafar. With Pakistan on the cusp of achieving democracy, one must relive the events that led to its halt on the day of 24 October 1954.

The mirror image of 10 April 2022 – 24 October 1954 (the First Constitutional Crisis & the First Military Coup)

On this day, the Punjabi G-G dismissed the Bengali-dominated First Constituent Assembly and promised fresh elections – which is exactly what Mr. Khan and his followers, continue to vociferously demand. The narrative of “fresh elections” was employed by him after the dissolution of the parliament, resulting in a political crisis amidst an ongoing economic crisis. The introduction of a constitutional crisis into the mix of crises afforded the military with a convenient entry into the political arena for the very first time in 1954. The Punjabi G-G was responsible for extending this invitation to the military multiple times. Just like Mr. Khan is calling out to the Mir Jafars of today, the Punjabi G-G had called out to Gen. Iskander Mirza in 1954, the descendant of Mir Jafar of folklore, only to disturb the institutional balance of power for almost seven decades. Is Mr. Khan unaware of the historical significance of demanding “fresh elections” after dissolving the National Assembly? As an expert on “Western democracy,” one would hope he is not entirely unaware. Yet, he continues to criticize the military for its adoption of an apolitical stance, in addition to threatening the country with fragmentation. If his supporters believe that he is naïve enough to be unaware, he should be made aware by educated segments that he is responsible for openly spreading undemocratic norms in society by following the autocratic legacy of Governor-General Malik Ghulam Muhammad.

Mr. Khan’s misuse of 63-A matches the G-G’s manipulation of the Damocles’ sword of disqualification, and that of defection – both of which dangled above the heads of politicians in the form of Public and Representative Office Disqualification Act (PRODA). The PM who enjoyed the VOC of the parliament, Sir Khwaja Nazimuddin, was unceremoniously dismissed on the basis of “conspiracies,” along with the entire assembly. The G-G claimed that the entire assembly ceased to be representative of the people of Pakistan as all of them were “ghaddars” involved in conspiracies against the state. On 10 April, Mr. Khan had full intentions of using this very claim to wipe off the parliament if only he had the judicial sanction to do so. His actions were clearly intended to generate a political crisis through the abuse of constitutional powers.

In terms of regard for the Constitution, the G-G axed the Constitution based on the democratic structure formulated by the Quaid. Instead, he helped develop the First Constitution of 1956 in which the title of Governor-General was morphed into the President, carrying the same dictatorial power structure that the Quaid was against. This role involved control over a) Governors – who can dismiss ministries and prevent oath-takings of CMs, and b) the Judiciary – that can accept the whimsical dissolution of assemblies on the basis of conspiracies. The makers of this first Constitution had their own version of Riyasat-e-Madinah; they called it the “Islamic Republic of Pakistan” and it was certainly not representative of the Quaid’s vision. Mr. Khan’s vision of the theocratic state of seventh century Madinah, based on the Presidential system of governance and deep regard for “rule of law”, bears striking similarity with the First Constitution of 1956. Moreover, the current power struggle in Punjab has proven Mr. Khan’s heightened potential for abuse of constitutional powers vested within the powerful roles he wishes to instate if given the chance to govern.

Moreover, opportunism is clearly visible in the common method employed by both, Mr. Khan and the G-G, in their respective pursuits of political power. Both entered politics when the arena was facing a political vacuum and democracy had eroded. After the passing away of the Quaid and Liaquat Ali Khan, the nation faced a political and an economic crisis simultaneously, much like the one today. Seven decades ago, the “anti-corruption narrative” was manufactured to generate polarization and societal divide. Mr. Khan has successfully brought our society to the same polarizing point again in 2022, where his party followers vehemently label supporters of all other parties as ghaddars.

Their communication strategy is almost identical. Rising to the occasion, both emerged as empowered Punjabis from the English-speaking upper-class of Lahore, claiming that the proof of their altruism is the foreign billionaire background that they left behind for the people of Pakistan. They displayed financial integrity which at that time was considered rare but welcomed as a virtue of the Quaid. The G-G claimed that he wanted to help build a “newer, stronger Pakistan” or Naya Pakistan for the post-Partition youth that grappled with limited employment opportunities in the midst of an economic crisis. With major plausible security threats, the military warranted high defence budgets. Poor economy in the presence of high defence expenditures made corrupt politicians a convenient excuse to deflect the public discourse from core economic and political issues.

Till date, Pakistan is globally known for allocating high defence budgets, yet PTI supporters are convinced that corruption is the sole reason behind economic crises. The disillusioned and uninformed youth of today with limited economic resources solely holds corrupt politicians responsible for their poor conditions, as was done in 1954. In the backdrop of such a strongly established anti-corruption narrative, financial integrity is certainly viewed as a highly attractive quality. It is especially an easy one to emulate for a power-hungry man – one who isn’t drawn to money, as claimed by both – the G-G in 1954, and Mr. Khan in 2022. Both used the Quaid’s virtues of integrity to further their politics, but eventually abused constitutional powers while governing disillusioned populaces. Clearly, world history and Pakistani history, both, are no strangers to power-hungry autocrats with clean banking records.

For the Quaid, “a constitutional lawyer of considerable perspicacity,” constitutional breaches were in fact, an anathema, as they clearly establish the desire for autocratic power in the perpetrator. Crimes against the Constitution that threaten the very existence of the nation must not be viewed lightly by the youth of a democratic nation. Both, Mr. Khan and the G-G, have inserted constitutional crises into an already prevailing mix of political and economic crises – connivingly designed to destabilize the nation. Basically, Mr. Khan tried to recreate the day of 24 October 1954, proof of which lies in the Mir Jafar reference. If Mr. Khan possessed the knowledge of and acted as per the strategy adopted by the G-G in 1954, he can be tried for sedition for attempting to conspire against the state using history as a reference.

The Presidential system the state of Madinah was instated by a Militablishment-backed and run government of Gen. Ayub Khan and Gen. Iskander Mirza in 1956. With Mir Jafar references, maybe Mr. Khan wants to take us back to that pre-democratic era. Moreover, Pakistan has been in a state of “incomplete Constitution-making” since its inception because the Constitution that the Quaid desired could not be actualized in its entirety. It is important to realise that Pakistan was formed on democratic norms instilled in us by the Quaid and questioning those very norms is tantamount to questioning the existence of Pakistan, along with questioning the vision of the Quaid for a democratically elected Muslim population of the Subcontinent.

Mr. Khan’s refusal to join the democratic setup and consistent denials of entering the political arena despite calls by the Government are indicative of the disruptive politics he wishes to engage in – the old “All or None” principle adopted by extremists with autocratic tendencies. While there are challenges, there are wins, too. The state institutions and the Judiciary neutralized the impact of Mr. Khan’s constitutional breaches on the institutional balance of power. In formulating his defense, Mr. Khan targeted the apt roles of institutions and the judiciary that followed historic judgments. He hoodwinked his supporters to criticise the applaudable role of the Judiciary in successfully burying the doctrine of necessity. Finally, the erstwhile Militablishment officially metamorphosed into the military after recognising its stance as apolitical, putting rest to seven decades of torment at the hands of hybrid regimes and ushering in the possibility of a democratic era. Unfortunately, the crowds around Mr. Khan who heard his references to Mir Jafar are uninformed and unaware of Mr. Khan’s viciousness.

I held detailed personalised interviews with 86 adult (25-35 years of age) PTI supporters, male and female (1:1 ratio) all from educated segments of society. They were asked to take a survey on General Knowledge.

Most of the respondents did not know that the VONC is a part of all democracies; hence their undemocratic opinions are pardonable, but Mr. Khan’s rejection of this democratic process, being an expert on “Western democracy,” is tantamount to spreading undemocratic norms in society. #Emergency (Twitter, 9 April)

Most of the respondents were unaware of the legal concept of the doctrine of necessity; hence, the Judiciary’s legal maturity was poorly understood by them. Mr. Khan made this segment of society question the democratic norm of “institutional neutrality” along with the misuse of religion as a tactic (neutral sirf janwar hota hai) – this is tantamount to spreading undemocratic norms in society. #SurrenderBajwa (Twitter, 10 April)

All of the respondents selected the “anti-corruption narrative” as being their main reason for supporting him – a narrative being employed since decades to promote societal divide in a highly political society.

Sadly, all of them said that if Mr. Khan were to leave PTI, they will cease to extend their support to PTI. This is reflective of an autocratic power-sharing model where the entire party structure is dependent on one individual’s hero worship.

Mr. Khan has clearly earned an audience through half-truths and selective narratives and clearly does not believe in the democratic power-sharing model. The results of this survey are proof to his indoctrination of a societal segment.

While Mr. Khan claims that he follows the virtues of the Quaid, he acts in a manner that is clearly quite contrary to it. Could this be the case of political domination by a power-hungry, English-speaking, tall and dapper, Punjabi (with a Pathan background) from the upper class of Lahore? History shows that it is possible and sometimes chillingly similar, as highlighted by Dr. Yaqoob Khan Bangash.

Dr. Paula Newberg starts her book Judging the State (1995) with a quote from Ghalib: “The beginning of a thing is a mirror of its end.” An undemocratic reign has been put to an end in coincidentally the same sequence of events during a night of the holiest month of the Muslim calendar. I hope provincial and political divides cease to plague us and we come together to participate in a democratic process where we observe the virtues and principles of the Quaid rather than those that commit constitutional breaches that are an anathema to the very foundation of this nation. We deserve an end to the “political horizon charred by extended periods of rule by a predominantly Punjabi military and bureaucracy” as written by Dr. Ayesha Jalal. For that, it is essential to formulate our political choices based on relevant facts rather than engaging in political discourse revolving around conspiracies.

Even the G-G’s reign in 1954 was known as “saazishon ka daur.” I pray that we enter “Naya Daur” instead. For a nation formed on the basis of the constitutional rights of Muslims in the Subcontinent, it is essential to further the democratic principles that are enshrined in its very foundation.