Recently, Prime Minister Imran Khan relied on an opinion survey result to yet again berate people who are critical of his Punjab satrap, Sardar Usman Buzdar. The survey by a comparatively unknown local organisation, the Institute of Public Opinion Research, found that 45% of Punjabis gave Buzdar a favorable rating, while the other three chief ministers fared worse at the hands of their electorates.

Undoubtedly Imran Khan would be chuffed at this result, considering it a ringing vindication of his decision to install the then unknown man from Taunsa Sharif as Punjab chief minister and to retain him in office, notwithstanding a fair degree of pressure to the contrary from “influential” quarters.

The rationale given by Imran Khan for Buzdar’s appointment went like this: since the latter hailed from an acutely backward area, therefore he was best placed to understand the pain and suffering of the poor and downtrodden, and to change their lot for the better. Three-and-a-half years later, this quaint logic has continued to hold water for the prime minister, even though several impartial observers believe that the performance of the Punjab government has been generally lackluster and on Sardar Buzdar’s watch there is little evidence of an upswing in the fortunes of Punjab’s marginalised and toiling masses.

Notwithstanding the prime minister’s reasoning, there is a counter-theory to explain the selection of the Buzdar chieftain as Punjab chief minister. It simply amounts to the “Daultana syndrome”. The term describes the situation of unease, nervousness and anxiety plaguing the mind of a prime minister if s/he is confronted with a powerful Punjab chief executive. Therefore, for a prime minister to counter the menace of the Daultana syndrome, it is pivotal that the Punjab chief-ministership is occupied by a person cut from a different cloth than that of the late Mian Mumtaz Mohammed Khan Daultana of Luddan, District Vehari.

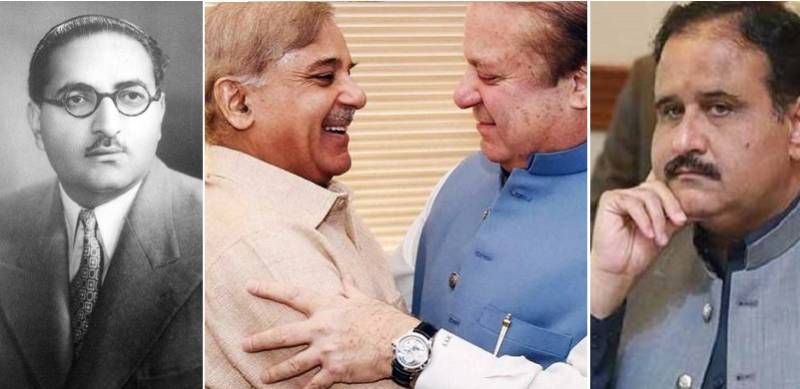

A bit of perspective is necessary. In the 1951 provincial assembly elections, Mumtaz Daultana, one of the premier landowners of the province, led the Punjab Muslim League to victory and became chief minister. Arguably the brightest and most intelligent politician of his generation, Daultana had an overweening ambition and reckless impatience for achieving the prime-ministership. In a dangerous move, he soon gave free rein to the growing anti-Qadiani movement in the province, considering it as a convenient means to destabilise the prime minister, East Pakistan’s Khawaja Nazimuddin.

Sadly for Daultana, his thirst for the premiership was to remain unquenched forever, since the ferocity of the unleashed religious passions in Punjab actually led to his own dismissal from office and the imposition of Pakistan’s first Martial Law in March 1953 (albeit localised to Punjab). In the words of Shakespeare, Daultana was felled by his “vaulting ambition which o’erleaps itself and falls on the other.”

But the grave misadventure of Mumtaz Daultana also further lowered the stock of Khawaja Nazimuddin, who was dismissed from office a month later by Governor-General Ghulam Mohammed. The whole episode made it clear to future prime ministers that their authority would rest on shifting sands, as long as the chief minister of the Punjab was not their loyal ally – if not a vassal.

Therefore, successive federal governments have sought to neutralise the sting of the Daultana syndrome by seeking, wherever possible, to secure the selection of a loyal Punjab chief minister.

And so, Daultana’s successors as chief ministers of the Punjab have broadly fallen into two categories.

The first comprises persons without any distinct power base, strong political credentials or prime-ministerial ambitions. These include men like Sardar Abdul Hameed Dasti, Malik Mairaj Khalid, Hanif Ramay, Sadiq Qureshi, Ghulam Hyder Wyne and Sardar Arif Nakai.

Each of these men diligently served the federal government. Except for Hanif Ramay, who showed a slightly independent streak and promptly lost office on that count, the rest never posed the slightest challenge to the prime minister of the day. Clearly, they were the complete antithesis of Mumtaz Daultana!

The second category of chief ministers comprises men who wielded executive authority and had a power base of their own but their relations with Islamabad ranged from active hostility to an uneasy cold war, punctuated with spurts of a mutually beneficial working relationship. Ghulam Mustafa Khar, Nawaz Sharif, Manzoor Wattoo and Shehbaz Sharif fall in this group.

A cursory look at the chief ministerial career of Nawaz Sharif, the most prominent member of this band, highlights the potency of the Daultana syndrome.

In 1985, Punjab Governor Lt General Ghulam Jillani Khan wished to break the stranglehold of the landed class on the chief-ministership, so he nominated an urbanite industrialist for this office. Using the considerable authority, patronage and pelf afforded by the chief ministerial position, in five years Nawaz Sharif built an independent power base which has stood the test of time in the succeeding three decades. This allowed him to stave off the challenge by Pir Pagara and prime minister Mohammed Khan Junejo in 1986 – they had sought to replace him with Chaudhry Pervaiz Ellahi – as well as by Benazir Bhutto in 1988, when she nominated Farooq Leghari for the Punjab chief-ministership. Further, Nawaz Sharif’s chief ministerial innings provided a springboard for an unprecedented three prime ministerial tenures. Therefore, Nawaz Sharif dexterously leveraged the office of Punjab chief minister to achieve the feat that Mumtaz Daultana failed to accomplish!

The moral of the story is that whenever a politician with an independent power-base occupies the chief ministerial residence in GOR 1 Lahore, the prime minister is haunted by the spirit of Mumtaz Daultana. With Usman Buzdar in the saddle, Imran Khan has laid this spectre to rest.

Of course, in the process he may have jeopardised, if not jettisoned, his party’s electoral prospects in the Punjab. But apparently, he is quite willing to take that risk rather than to run the gauntlet of the Daultana syndrome!

Undoubtedly Imran Khan would be chuffed at this result, considering it a ringing vindication of his decision to install the then unknown man from Taunsa Sharif as Punjab chief minister and to retain him in office, notwithstanding a fair degree of pressure to the contrary from “influential” quarters.

The rationale given by Imran Khan for Buzdar’s appointment went like this: since the latter hailed from an acutely backward area, therefore he was best placed to understand the pain and suffering of the poor and downtrodden, and to change their lot for the better. Three-and-a-half years later, this quaint logic has continued to hold water for the prime minister, even though several impartial observers believe that the performance of the Punjab government has been generally lackluster and on Sardar Buzdar’s watch there is little evidence of an upswing in the fortunes of Punjab’s marginalised and toiling masses.

Notwithstanding the prime minister’s reasoning, there is a counter-theory to explain the selection of the Buzdar chieftain as Punjab chief minister. It simply amounts to the “Daultana syndrome”. The term describes the situation of unease, nervousness and anxiety plaguing the mind of a prime minister if s/he is confronted with a powerful Punjab chief executive. Therefore, for a prime minister to counter the menace of the Daultana syndrome, it is pivotal that the Punjab chief-ministership is occupied by a person cut from a different cloth than that of the late Mian Mumtaz Mohammed Khan Daultana of Luddan, District Vehari.

Using the considerable authority, patronage and pelf afforded by the chief ministerial position, in five years Nawaz Sharif built an independent power base which has stood the test of time in the succeeding three decades

A bit of perspective is necessary. In the 1951 provincial assembly elections, Mumtaz Daultana, one of the premier landowners of the province, led the Punjab Muslim League to victory and became chief minister. Arguably the brightest and most intelligent politician of his generation, Daultana had an overweening ambition and reckless impatience for achieving the prime-ministership. In a dangerous move, he soon gave free rein to the growing anti-Qadiani movement in the province, considering it as a convenient means to destabilise the prime minister, East Pakistan’s Khawaja Nazimuddin.

Sadly for Daultana, his thirst for the premiership was to remain unquenched forever, since the ferocity of the unleashed religious passions in Punjab actually led to his own dismissal from office and the imposition of Pakistan’s first Martial Law in March 1953 (albeit localised to Punjab). In the words of Shakespeare, Daultana was felled by his “vaulting ambition which o’erleaps itself and falls on the other.”

But the grave misadventure of Mumtaz Daultana also further lowered the stock of Khawaja Nazimuddin, who was dismissed from office a month later by Governor-General Ghulam Mohammed. The whole episode made it clear to future prime ministers that their authority would rest on shifting sands, as long as the chief minister of the Punjab was not their loyal ally – if not a vassal.

Therefore, successive federal governments have sought to neutralise the sting of the Daultana syndrome by seeking, wherever possible, to secure the selection of a loyal Punjab chief minister.

And so, Daultana’s successors as chief ministers of the Punjab have broadly fallen into two categories.

The first comprises persons without any distinct power base, strong political credentials or prime-ministerial ambitions. These include men like Sardar Abdul Hameed Dasti, Malik Mairaj Khalid, Hanif Ramay, Sadiq Qureshi, Ghulam Hyder Wyne and Sardar Arif Nakai.

Each of these men diligently served the federal government. Except for Hanif Ramay, who showed a slightly independent streak and promptly lost office on that count, the rest never posed the slightest challenge to the prime minister of the day. Clearly, they were the complete antithesis of Mumtaz Daultana!

The second category of chief ministers comprises men who wielded executive authority and had a power base of their own but their relations with Islamabad ranged from active hostility to an uneasy cold war, punctuated with spurts of a mutually beneficial working relationship. Ghulam Mustafa Khar, Nawaz Sharif, Manzoor Wattoo and Shehbaz Sharif fall in this group.

A cursory look at the chief ministerial career of Nawaz Sharif, the most prominent member of this band, highlights the potency of the Daultana syndrome.

In 1985, Punjab Governor Lt General Ghulam Jillani Khan wished to break the stranglehold of the landed class on the chief-ministership, so he nominated an urbanite industrialist for this office. Using the considerable authority, patronage and pelf afforded by the chief ministerial position, in five years Nawaz Sharif built an independent power base which has stood the test of time in the succeeding three decades. This allowed him to stave off the challenge by Pir Pagara and prime minister Mohammed Khan Junejo in 1986 – they had sought to replace him with Chaudhry Pervaiz Ellahi – as well as by Benazir Bhutto in 1988, when she nominated Farooq Leghari for the Punjab chief-ministership. Further, Nawaz Sharif’s chief ministerial innings provided a springboard for an unprecedented three prime ministerial tenures. Therefore, Nawaz Sharif dexterously leveraged the office of Punjab chief minister to achieve the feat that Mumtaz Daultana failed to accomplish!

The moral of the story is that whenever a politician with an independent power-base occupies the chief ministerial residence in GOR 1 Lahore, the prime minister is haunted by the spirit of Mumtaz Daultana. With Usman Buzdar in the saddle, Imran Khan has laid this spectre to rest.

Of course, in the process he may have jeopardised, if not jettisoned, his party’s electoral prospects in the Punjab. But apparently, he is quite willing to take that risk rather than to run the gauntlet of the Daultana syndrome!