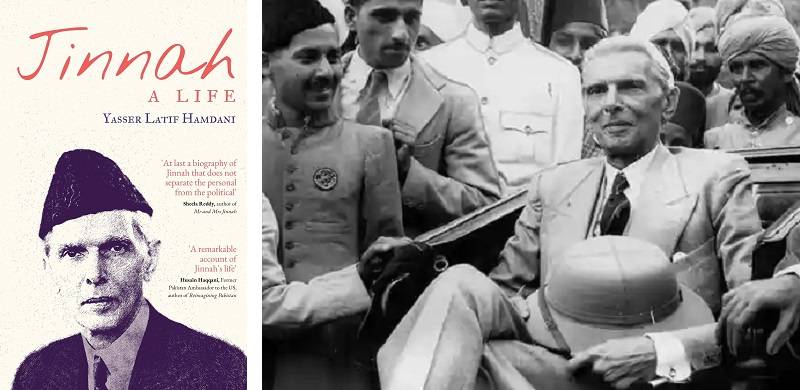

I came across Dhruv Rathee’s video that equates Jinnah with Savarkar based on communalism. Rathee is young YouTuber with a large following. In the age that is obsessed with a fan following, short media bites, and good looks, I turned to Yasser Latif Hamdani for his input. I did so because I’ve not found the passion and brilliance with which he writes on Jinnah elsewhere. He directed me to his book Jinnah: A Life and mentioned that he could not respond to every other person on the subject. I found my answer on page 189, where Hamdani writes, “Savarkar believed in one India with two nations where the Hindu nation dominated the Muslim nation. Jinnah, instead, argued parity or separate federations. Most of Muslim League supporters were of a democratic mindset and not necessarily the religious fanatics.” (p. 189). I understood Hamdani’s position, as I have been following his articles off and on for more than a decade on various platforms including Chowk, Pak Tea House, Daily Times and Naya Daur. A few years ago, I had also bought his 2012 book on Jinnah: Myth and Reality, which I left in my office for an opportune time. Through the years, Hamdani has weaved a consistent and valiant narrative on Jinnah and I for one find his dedication awe inspiring.

Many Pakistanis in various parts of the world are too consumed by livelihood matters to have much time for things that matter to our identity. Though, concerns arise from time to time, as we witness the rise of radical Islamist parties in Pakistan and the equally radical Hindutva brigade that holds the most contemptuous of Islamophobic tropes. Increasing trolling by Hindutva Indians on social media, who are seemingly obsessed with every other news pertaining to Pakistan, incentivised me to read Hamdani’s latest book. While I do not find constitutional matters and politics the least bit interesting, I laboured through his book to find a narrative on the Quaid-e-Azam that is not besmirched by the prejudiced Hindutva or the Islamist crowds – or for that matter Indian Muslim leaders who egregiously rail against Pakistan and Jinnah to prove their loyalty to India. Although Indian Muslims would know that Jinnah counselled them “in no uncertain terms, that they should be loyal to India, and that they should not seek to ride two horses.” (p. 232).

A holistic not atomistic approach

Hamdani’s orientation links with mine, as he does not adopt an atomistic approach of obsessing with contradictory texts to score cheap points. Instead, he adopts a holistic approach by collecting all the texts, placing them in a context and reconciling them to get a clearer picture of the issue. This is important to understand, as the atomistic approach mars the Islamic discourse of extremists who take verses out of their context to further their respective agendas. I also like Hamdani’s approach because he does not try to put a person in a neat box for classification. Human beings do not think in binary terms but grow organically as they are shaped by their lived experiences. Thus, Hamdani showcases that where a humbly clad Gandhi could not mesh with the Dalit leader Dr. Ambedkar (p. 188) but could gel with religious conservatives, a western dressed Mr. M.A. Jinnah could lead a coalition of minorities including Dalit leaders like Jogendra Nath Mandal, Ahmadis, and Punjabi Christians (p. 233), apart from the elite Muslims that characterised the Muslim League.

Parity not Partition

Hamdani’s book affirms Ayesha Jalal’s assessment that ‘It was Congress that insisted on partition. It was Jinnah who was against partition,’ (p. 217). Jinnah’s main goal did not lie in partition but in securing safeguards for Muslims based on parity, as the word “minority” could not be applied to a population in millions (p. 213). Hamdani uses the word consociationalism to argue that what Jinnah wanted was an entity like Canada where a federal government exists with autonomous provinces, as opposed to a powerful central government that would be dictated by majoritarian interests. This much becomes clear even after Partition, when Jinnah forgoes power imbued by Section 93, whereas Nehru behaves as a centrist dictator dismissing legislatures in Kerala and elsewhere (p. 267-268). Indeed, when one reads the 14 points including “residuary powers vested in the provinces” or that “the Muslim representation shall not be less than one third,” it becomes quite clear that Jinnah was not necessarily pursuing a partition but safeguards for the Muslims of India (p. 31), as “it would allow Muslims to block any legislation that they would deem inimical to their legitimate interests.” (p. 113)

Jinnah’s understanding of Islam

Additionally, like Dr. Taimur Rahman who views Jinnah’s references to “Islam” or personal “shariat law” through the modernist lens of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, Hamdani weaves a consistent narrative on Jinnah’s vision for a secular democracy and views his references to “Islam” as compatible with the ideas of equality, justice and fair play (p. 244). Hamdani draws upon Faisal Devji, who argued that such an Islam was “ontologically emptied, a secularised husk, which provided the broad contours of identity and not really the substance and basis for things like legislation and polity.” (p. 174) It is also important to underscore that Jinnah resented Gandhi’s use of religious symbols and ideas in politics, as they would eventually flare up communal identities instead of diminishing them (p. 81). Moreover, he was alarmed at “Gandhi’s championing of the orthodox religious demands of narrow-Muslims in wake of the Khilafat Movement” (p. 81). In contrast, “Jinnah would remark that Ataturk was not just the greatest Mussalman of the age but one of the greatest men to ever live” (p. 127). In essence, upholding a secular approach, “Jinnah had become a subject of ridicule for his western clothes, constitutional ideas and his resistance to the idea of mixing religion with politics” (p. 90). Indeed, he didn’t think much of the “undesirable element of Maulvis and Maulanas” (pp. 165-166), had little patience for outward displays of religiosity (p. 243) and for him, “pan-Islamism was a bogey that had exploded.” (p. 214)

Jinnah defies labels

The narrative Hamdani weaves includes the ideas that Jinnah’s ambition was to become the Muslim Gokhale (p. 17) and that he started the tradition of speaking truth to power (p. 23), as he found himself against the British, the Congress, and the Muslim elite and religious Muslims alike. Such stiff opposition across the board had to eventually take a toll on his body and helps explain his icy cold exterior. It reminds me of the Amin Ahsan Islahi’s motto, “Abide by the truth even if your shadow deserts you.” All of this indicates that this is not a person who craves power for he willingly ceded it, that he was not out there for knighthood and titles that were granted to the pro British Muslim elite (p. 99), and that he could not be labelled in a box, as he was too proper for the Labour party and too liberal for the Conservative party (p. 124) and that where he offered the defense of Ilam Din, he had also done the same for Bal Gangadhar Tilak, the leader of the so-called extremist group within the Congress. (p. 39).

Additionally, his secular orientation is noted not so much so through personal choices of consuming alcohol and ham sandwiches or his defense of the scandalous low-cut dresses of his spouse Ruttie (p. 66-67) but through his vocal support for inter-communal marriages (p. 24). His words are important to note especially today, as Muslims grapple with the issues of inter-faith and same-sex marriages.

“[…] if there is a fairly large class of enlightened, educated, advanced Indians, be they Hindus, Mohammedans, or Parsis, and if they wish to adopt a system of marriage, which is in accord with the modern civilisation and ideas of modern times, more in accord with modern sentiments, why should that class be denied justice?’ (p. 25).

The fact that Jinnah defies boxes and labels needs to be appreciated. This means that one must reject the simplistic caricatures from a Pakistani Islamist or an Indian Hindutva angle. And Hamdani does excellent work in dispelling those caricatures, not so much by apologetics but by letting the facts speak for themselves. For instance, it must be appreciated that “Jinnah’s work in the legislature laid the foundations not just of a military academy but also the Supreme Court” (p. 111). Indeed, such contributions should never be sidelined to nurse prejudiced narratives that rest on unsubstantiated falsehoods and slander like “we shall have India divided or destroyed” (p. 206).

Two Nation Theory?

Hamdani also sets the record straight that “At no point did the much-maligned Two Nation Theory ever say that Hindus and Muslims could not live together in one state.” (p. 158). Moreover, he argues that “the demand for separatism was always more of a paper tiger, raised to scare the Congress and its leadership into behaving better and coming to a settlement with the Muslims at an all India level.” (p. 162). Continuing with this line of thought, Hamdani references H. V. Hodson, the Reforms Commissioner in India in 1941, who “believed that ‘Pakistan’ was a ‘revolt against minority status’ and a call for power sharing” (p. 175). Additionally, Hamdani argues that Jinnah’s arguing against the partition of Punjab and Bengal “was as clear a negation of the Two Nation Theory as could be.” (p. 216). Furthermore, “it was Congress that deployed the Two Nation Theory to partition both Punjab and Bengal and the Muslim League that voted to keep Punjab and Bengal united.” (p. 221) Hamdani also mentions that, as late as 21 May 1947, Jinnah said in his interview that, “This idea of partition is not only thoughtless and reckless, but […] it will be a grave error and will prove dangerous immediately and far more so in the future.” (p. 218)

What If?

Hamdani also writes that that “in the 1940s at least, [the two nations theory] was forwarded by two men – Ambedkar and Jinnah – who were perhaps the most secular-minded politicians in South Asia.” (pp. 176-177) He adds that that Jinnah was highly regarded by many Indians including “Sir Cattamanchi Ramalinga Reddy, the great Indian educationist, [who] called him ‘the pride of India and not the exclusive possession of the Muslims’ [and] […] Mylai Chinna Thambi Pillai Rajah, the Tamil politician and scheduled caste leader, who [said]: ‘All religions hold the belief that God sends suitable men into the world to work out his plans from time to time, and at critical junctures. I regard Mr Jinnah as the man who has been called upon to correct the wrong ways into which the people of India have been led by the Congress [...] [H]e is championing the claims of all classes who stand the danger of being crushed under the steam roller of a caste Hindu majority.’” (p. 179-180)

This is why Hamdani wonders if instead of an All India Muslim League, Jinnah should have banded with such leaders to work on an All India Minorities League (p. 180) along with the support of the Communist Party of India (p. 189). However, anyone who has worked for a just cause knows that getting people together is like herding stray cats and at times can be a thankless job. Time and energy are limited and one cannot expect someone whose body was afflicted with disease and who was working round the clock to fulfill multiple musings of “what ifs.”

The crystallization of Yasser Latif Hamdani’s ideas

Through meticulous research informed by years of sustained dialogue and debates, Hamdani seems to have crystallised his thoughts in his book. He makes a strong case that it wasn’t partition that Jinnah wanted but rather safeguard of Muslim interests based on parity and he rejected the idea of a minority dictated by majoritarian interests. The fact that Jinnah planned to retire in Bombay (p. 234), viewed “India above Hindustan and Pakistan”, as a secular multicultural federal state (pp. 207-208), spoke of a relationship like US and Canada between the future states in India (p. 212), and emphasised standing together against any aggressive outsider (p. 219), and suggested that the new constituent assemblies of Pakistan and Hindustan meet in New Delhi. (pp. 223-224), all substantiate the thesis against partition and towards a federation where the minority interests are of paramount significance. Hamdani is clear that Jinnah rejected a theocracy for he omitted the words ‘so help me God’ and insisted on changing the word ‘swear’ to ‘affirm’ in the oath taking ceremony (p. 236). Additionally, Jinnah’s commitment to a secular state was noted in the Indian Constituent Assembly by M. Ananthasayanam Ayyangar on 27 August 1947, when he quoted Jinnah: “My idea is to have a secular State here.” (p. 241-242) Indeed, Jinnah reinforced the idea that, “In any case Pakistan is not going to be a theocratic State – to be ruled by priests with a divine mission.” (p. 248)

Where do we go from here?

Finally, Hamdani writes that while we have Jinnah’s picture on every wall and currency note, his ideas have been forgotten and remain irrelevant to contemporary Pakistan. This much is true in India as well where Gandhi is increasingly being replaced by the likes of Savarkar. But whatever India decides is their concern. Pakistanis in Pakistan and across the globe in the Diaspora will have to focus on their own hero, the Quaid-e-Azam. If he is to be honoured, then we will have to revive a secular democracy, reinstate the right of Ahmadis to profess their beliefs as equal citizens, end the systemic discrimination and persecution of minorities, mercilessly end the nightmare of fanaticism and extremism, and make Pakistan into one of the strongest nations of the world.

Many Pakistanis in various parts of the world are too consumed by livelihood matters to have much time for things that matter to our identity. Though, concerns arise from time to time, as we witness the rise of radical Islamist parties in Pakistan and the equally radical Hindutva brigade that holds the most contemptuous of Islamophobic tropes. Increasing trolling by Hindutva Indians on social media, who are seemingly obsessed with every other news pertaining to Pakistan, incentivised me to read Hamdani’s latest book. While I do not find constitutional matters and politics the least bit interesting, I laboured through his book to find a narrative on the Quaid-e-Azam that is not besmirched by the prejudiced Hindutva or the Islamist crowds – or for that matter Indian Muslim leaders who egregiously rail against Pakistan and Jinnah to prove their loyalty to India. Although Indian Muslims would know that Jinnah counselled them “in no uncertain terms, that they should be loyal to India, and that they should not seek to ride two horses.” (p. 232).

A holistic not atomistic approach

Hamdani’s orientation links with mine, as he does not adopt an atomistic approach of obsessing with contradictory texts to score cheap points. Instead, he adopts a holistic approach by collecting all the texts, placing them in a context and reconciling them to get a clearer picture of the issue. This is important to understand, as the atomistic approach mars the Islamic discourse of extremists who take verses out of their context to further their respective agendas. I also like Hamdani’s approach because he does not try to put a person in a neat box for classification. Human beings do not think in binary terms but grow organically as they are shaped by their lived experiences. Thus, Hamdani showcases that where a humbly clad Gandhi could not mesh with the Dalit leader Dr. Ambedkar (p. 188) but could gel with religious conservatives, a western dressed Mr. M.A. Jinnah could lead a coalition of minorities including Dalit leaders like Jogendra Nath Mandal, Ahmadis, and Punjabi Christians (p. 233), apart from the elite Muslims that characterised the Muslim League.

Parity not Partition

Hamdani’s book affirms Ayesha Jalal’s assessment that ‘It was Congress that insisted on partition. It was Jinnah who was against partition,’ (p. 217). Jinnah’s main goal did not lie in partition but in securing safeguards for Muslims based on parity, as the word “minority” could not be applied to a population in millions (p. 213). Hamdani uses the word consociationalism to argue that what Jinnah wanted was an entity like Canada where a federal government exists with autonomous provinces, as opposed to a powerful central government that would be dictated by majoritarian interests. This much becomes clear even after Partition, when Jinnah forgoes power imbued by Section 93, whereas Nehru behaves as a centrist dictator dismissing legislatures in Kerala and elsewhere (p. 267-268). Indeed, when one reads the 14 points including “residuary powers vested in the provinces” or that “the Muslim representation shall not be less than one third,” it becomes quite clear that Jinnah was not necessarily pursuing a partition but safeguards for the Muslims of India (p. 31), as “it would allow Muslims to block any legislation that they would deem inimical to their legitimate interests.” (p. 113)

Jinnah’s understanding of Islam

Additionally, like Dr. Taimur Rahman who views Jinnah’s references to “Islam” or personal “shariat law” through the modernist lens of Sir Syed Ahmad Khan, Hamdani weaves a consistent narrative on Jinnah’s vision for a secular democracy and views his references to “Islam” as compatible with the ideas of equality, justice and fair play (p. 244). Hamdani draws upon Faisal Devji, who argued that such an Islam was “ontologically emptied, a secularised husk, which provided the broad contours of identity and not really the substance and basis for things like legislation and polity.” (p. 174) It is also important to underscore that Jinnah resented Gandhi’s use of religious symbols and ideas in politics, as they would eventually flare up communal identities instead of diminishing them (p. 81). Moreover, he was alarmed at “Gandhi’s championing of the orthodox religious demands of narrow-Muslims in wake of the Khilafat Movement” (p. 81). In contrast, “Jinnah would remark that Ataturk was not just the greatest Mussalman of the age but one of the greatest men to ever live” (p. 127). In essence, upholding a secular approach, “Jinnah had become a subject of ridicule for his western clothes, constitutional ideas and his resistance to the idea of mixing religion with politics” (p. 90). Indeed, he didn’t think much of the “undesirable element of Maulvis and Maulanas” (pp. 165-166), had little patience for outward displays of religiosity (p. 243) and for him, “pan-Islamism was a bogey that had exploded.” (p. 214)

Jinnah defies labels

The narrative Hamdani weaves includes the ideas that Jinnah’s ambition was to become the Muslim Gokhale (p. 17) and that he started the tradition of speaking truth to power (p. 23), as he found himself against the British, the Congress, and the Muslim elite and religious Muslims alike. Such stiff opposition across the board had to eventually take a toll on his body and helps explain his icy cold exterior. It reminds me of the Amin Ahsan Islahi’s motto, “Abide by the truth even if your shadow deserts you.” All of this indicates that this is not a person who craves power for he willingly ceded it, that he was not out there for knighthood and titles that were granted to the pro British Muslim elite (p. 99), and that he could not be labelled in a box, as he was too proper for the Labour party and too liberal for the Conservative party (p. 124) and that where he offered the defense of Ilam Din, he had also done the same for Bal Gangadhar Tilak, the leader of the so-called extremist group within the Congress. (p. 39).

Additionally, his secular orientation is noted not so much so through personal choices of consuming alcohol and ham sandwiches or his defense of the scandalous low-cut dresses of his spouse Ruttie (p. 66-67) but through his vocal support for inter-communal marriages (p. 24). His words are important to note especially today, as Muslims grapple with the issues of inter-faith and same-sex marriages.

“[…] if there is a fairly large class of enlightened, educated, advanced Indians, be they Hindus, Mohammedans, or Parsis, and if they wish to adopt a system of marriage, which is in accord with the modern civilisation and ideas of modern times, more in accord with modern sentiments, why should that class be denied justice?’ (p. 25).

The fact that Jinnah defies boxes and labels needs to be appreciated. This means that one must reject the simplistic caricatures from a Pakistani Islamist or an Indian Hindutva angle. And Hamdani does excellent work in dispelling those caricatures, not so much by apologetics but by letting the facts speak for themselves. For instance, it must be appreciated that “Jinnah’s work in the legislature laid the foundations not just of a military academy but also the Supreme Court” (p. 111). Indeed, such contributions should never be sidelined to nurse prejudiced narratives that rest on unsubstantiated falsehoods and slander like “we shall have India divided or destroyed” (p. 206).

Two Nation Theory?

Hamdani also sets the record straight that “At no point did the much-maligned Two Nation Theory ever say that Hindus and Muslims could not live together in one state.” (p. 158). Moreover, he argues that “the demand for separatism was always more of a paper tiger, raised to scare the Congress and its leadership into behaving better and coming to a settlement with the Muslims at an all India level.” (p. 162). Continuing with this line of thought, Hamdani references H. V. Hodson, the Reforms Commissioner in India in 1941, who “believed that ‘Pakistan’ was a ‘revolt against minority status’ and a call for power sharing” (p. 175). Additionally, Hamdani argues that Jinnah’s arguing against the partition of Punjab and Bengal “was as clear a negation of the Two Nation Theory as could be.” (p. 216). Furthermore, “it was Congress that deployed the Two Nation Theory to partition both Punjab and Bengal and the Muslim League that voted to keep Punjab and Bengal united.” (p. 221) Hamdani also mentions that, as late as 21 May 1947, Jinnah said in his interview that, “This idea of partition is not only thoughtless and reckless, but […] it will be a grave error and will prove dangerous immediately and far more so in the future.” (p. 218)

What If?

Hamdani also writes that that “in the 1940s at least, [the two nations theory] was forwarded by two men – Ambedkar and Jinnah – who were perhaps the most secular-minded politicians in South Asia.” (pp. 176-177) He adds that that Jinnah was highly regarded by many Indians including “Sir Cattamanchi Ramalinga Reddy, the great Indian educationist, [who] called him ‘the pride of India and not the exclusive possession of the Muslims’ [and] […] Mylai Chinna Thambi Pillai Rajah, the Tamil politician and scheduled caste leader, who [said]: ‘All religions hold the belief that God sends suitable men into the world to work out his plans from time to time, and at critical junctures. I regard Mr Jinnah as the man who has been called upon to correct the wrong ways into which the people of India have been led by the Congress [...] [H]e is championing the claims of all classes who stand the danger of being crushed under the steam roller of a caste Hindu majority.’” (p. 179-180)

This is why Hamdani wonders if instead of an All India Muslim League, Jinnah should have banded with such leaders to work on an All India Minorities League (p. 180) along with the support of the Communist Party of India (p. 189). However, anyone who has worked for a just cause knows that getting people together is like herding stray cats and at times can be a thankless job. Time and energy are limited and one cannot expect someone whose body was afflicted with disease and who was working round the clock to fulfill multiple musings of “what ifs.”

The crystallization of Yasser Latif Hamdani’s ideas

Through meticulous research informed by years of sustained dialogue and debates, Hamdani seems to have crystallised his thoughts in his book. He makes a strong case that it wasn’t partition that Jinnah wanted but rather safeguard of Muslim interests based on parity and he rejected the idea of a minority dictated by majoritarian interests. The fact that Jinnah planned to retire in Bombay (p. 234), viewed “India above Hindustan and Pakistan”, as a secular multicultural federal state (pp. 207-208), spoke of a relationship like US and Canada between the future states in India (p. 212), and emphasised standing together against any aggressive outsider (p. 219), and suggested that the new constituent assemblies of Pakistan and Hindustan meet in New Delhi. (pp. 223-224), all substantiate the thesis against partition and towards a federation where the minority interests are of paramount significance. Hamdani is clear that Jinnah rejected a theocracy for he omitted the words ‘so help me God’ and insisted on changing the word ‘swear’ to ‘affirm’ in the oath taking ceremony (p. 236). Additionally, Jinnah’s commitment to a secular state was noted in the Indian Constituent Assembly by M. Ananthasayanam Ayyangar on 27 August 1947, when he quoted Jinnah: “My idea is to have a secular State here.” (p. 241-242) Indeed, Jinnah reinforced the idea that, “In any case Pakistan is not going to be a theocratic State – to be ruled by priests with a divine mission.” (p. 248)

Where do we go from here?

Finally, Hamdani writes that while we have Jinnah’s picture on every wall and currency note, his ideas have been forgotten and remain irrelevant to contemporary Pakistan. This much is true in India as well where Gandhi is increasingly being replaced by the likes of Savarkar. But whatever India decides is their concern. Pakistanis in Pakistan and across the globe in the Diaspora will have to focus on their own hero, the Quaid-e-Azam. If he is to be honoured, then we will have to revive a secular democracy, reinstate the right of Ahmadis to profess their beliefs as equal citizens, end the systemic discrimination and persecution of minorities, mercilessly end the nightmare of fanaticism and extremism, and make Pakistan into one of the strongest nations of the world.