It’s the end of the school year and at work almost the end of the fiscal year. Most of my colleagues and I agree that we feel as if we are in the last leg of a marathon, where every step drags with weariness and the finishing line is within reach.

What makes it harder is that everything happens at the same time – work pressure, end of school meetings and farewells before the summer begins. How can one do it all and at the same time? The simple answer is that we can’t. It is still important to prioritize – choose what is important and what utility it has in our lives.

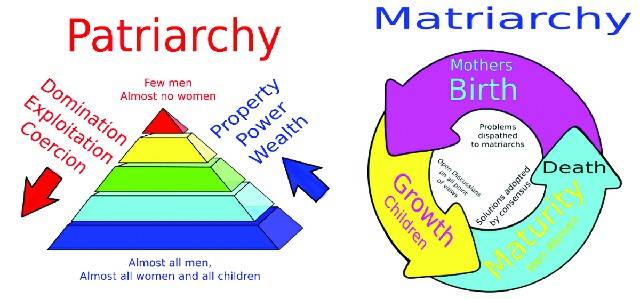

My day job is to do with productive labour. It is invisible work yet has a value to the world. What I do at home is equally important, perhaps more crucial, for I am a mother, daughter and wife and friend. We survive in a capitalist system – where the construct of value is paid on renumerated activities. “Work,” for instance, is linked to growth and Gross Domestic Product (GDP). That has a transactional value. The capitalist system, therefore, imposes a system in which non-primary producers do not have worth for society at large. Anything domestic does not count as ‘work’ or ‘labour’. Even worse, it is classified as ‘leisure time.’ All the time you spend cleaning and tidying and decluttering; or doing homework with your children; or spending time with elderly relatives, is actually leisure time – though it may not feel like it! As it cannot be measured, it cannot be counted and does not have extrinsic worth or value. Having a baby or looking after one? Sorry - unproductive. No points for any of this invisible work.

Time aftertime, country after country, research indicates that this unpaid sector is as large as the formal sector of paid work, whether earned through financial services, manufacturing or retailing goods. These values of ‘worth’ seem ridiculously archaic for the 21st century. They are heavily, unfairly geared towards men’s notions of productivity. Women are disproportionately affected, particularly during the COVID lockdown. In fact, women are encouraged to lean in to the system but not change the way the system works – even though, clearly, this distorted system does not work for half of the world.

There are obvious limitations to such an approach. Take how capitalism considers forests and trees. Forests have a monetary value to the extent that trees are chopped into timber and then sold. How does one value growing trees that contribute to better air, control the climate, improve the quality of human life?

As a trained economist and a working mother, it should be easier for me to reconcile the day and night aspects of my daily life. But to the way worth is calculated nowadays, it is difficult to reconcile! After all, one has to accept that things which are – to me – important aspects of my personal life, simply do no hold worth outside my home-relationships. The advent of a gig economy – think Facebook, Airbnb and other more flexible professions – has not fundamentally changed public policy, even as they outpace it.

For that reason alone, Bhutan is a model working eco-system. My first exposure to Bhutan was before I visited it. A Japanese colleague had traded in lucrative job at McKinsey in Tokyo to work with the Bhutanese authorities, helping them design and implement the Gross Happiness Index (GHI).

The idea was to develop measurable indicators as to the value of life. Each time the population is asked questions, their life style and habits are taken into consideration: how often they participate in community activities, visit family, commune and pray in temples, engage in spiritual retreat?

In this concept, GDP counts, but it is only one factor taken into consideration. Happiness arises not just from workers’ productivity but from their sense of community and the quality of their lives. The fact that these indicators can be quantified, measured as ‘worth,’ means that people think about them differently. Just making people aware of how to think of issues is important to start the debate.

And frankly it’s time for that. I work in a multicultural environment in the US where people routinely complain about South Asian and Middle Eastern men taking longer to catch up on political correctness and how to treat women colleagues. I bristle at the thought of my compatriots being culturally deficient until I remember my own experiences at work over two decades. It was always the desi male middle-age colleagues who would ask me whether I was taking a half-day when I would log off to feed a three month-old baby One particular repeat offender would also give five minute breaks to female assistants for bathroom breaks and then wonder why they had been away for longer. The European and American colleagues were actually supportive and encouraging –particularly as they had wives or mothers who were in the same situation. My anecdotes are unfortunately not unique – ask any women you know who works and you shall hear similar narratives.That kind of chauvinistic behavior is outdated and unacceptable, regardless of the cultural context. We may laugh it off as eccentricity but when the person holds a position of power, then this kind of behaviour sets the worst kind of example of toxic masculinity.

Now, I am older and more tempered. I have ready responses on now how to deal with behaviour like that. Early on in my career, I was constantly trying to prove myself (like most working mothers). It was hard enough performing, managing and juggling it all without being micromanaged as to your use of time. Conversely, it was often the lives of these colleagues who would wonder why their husbands kept very late hours, unaware that their better halves spent half the day playing squash, having long ‘business’ lunches and reading online newspapers at work. I smiled when they complained about their husband’s working hours, when I would witness how much “leisure” time their husbands spent at work.

Being in the office was considered “work”; leisure such as childcare and home responsibilities were relegated to the women a home. Men “baby sit” their kids, mothers parent them. We give kudos to men for being involved or hands-on with their children but take the same for granted when done by a mother. Even the language one uses can demean the woman’s contribution to the family partly as its considered invisible work which has no monetary value – though clearly the societal value is priceless. It is critical to leave our children with caring givers, important for us to have teachers who support our children in learning as it is important for them to see positivity in doing household work. To keep things going, it’s often the woman who plays the Chief Admin Officer of a family – whether remembering doctors’ appointments, planning school play dates or whether to go out or not. Some go as far to receive “pocket money” from their husbands, if they are not financially independent.

When taught about game theory and the sense of public good, it is very clear that we need to do better as a society about things that have value and use language and practice to support that belief. Many of the 21st-century issues – whether gender, climate, race, technology – will require a fundamental rethink of what the impact is for both men and women. It will mean recalibrating our assumptions. Our values matter only if they also embrace equity, fairness and a sense of empathy. Demeaning women, whether in the home or as a sitting Prime Minister, will not lead to a better outcome for society as a whole.

Leadership, use of appropriate language and behaviour – all of these matter. And that has been proved over centuries by a middle-aged man who did understand both value and worth very well indeed: Adam Smith!

What makes it harder is that everything happens at the same time – work pressure, end of school meetings and farewells before the summer begins. How can one do it all and at the same time? The simple answer is that we can’t. It is still important to prioritize – choose what is important and what utility it has in our lives.

My day job is to do with productive labour. It is invisible work yet has a value to the world. What I do at home is equally important, perhaps more crucial, for I am a mother, daughter and wife and friend. We survive in a capitalist system – where the construct of value is paid on renumerated activities. “Work,” for instance, is linked to growth and Gross Domestic Product (GDP). That has a transactional value. The capitalist system, therefore, imposes a system in which non-primary producers do not have worth for society at large. Anything domestic does not count as ‘work’ or ‘labour’. Even worse, it is classified as ‘leisure time.’ All the time you spend cleaning and tidying and decluttering; or doing homework with your children; or spending time with elderly relatives, is actually leisure time – though it may not feel like it! As it cannot be measured, it cannot be counted and does not have extrinsic worth or value. Having a baby or looking after one? Sorry - unproductive. No points for any of this invisible work.

Time aftertime, country after country, research indicates that this unpaid sector is as large as the formal sector of paid work, whether earned through financial services, manufacturing or retailing goods. These values of ‘worth’ seem ridiculously archaic for the 21st century. They are heavily, unfairly geared towards men’s notions of productivity. Women are disproportionately affected, particularly during the COVID lockdown. In fact, women are encouraged to lean in to the system but not change the way the system works – even though, clearly, this distorted system does not work for half of the world.

One has to accept that things which are – to me – important aspects of my personal life, simply do no hold worth outside my home-relationships

There are obvious limitations to such an approach. Take how capitalism considers forests and trees. Forests have a monetary value to the extent that trees are chopped into timber and then sold. How does one value growing trees that contribute to better air, control the climate, improve the quality of human life?

As a trained economist and a working mother, it should be easier for me to reconcile the day and night aspects of my daily life. But to the way worth is calculated nowadays, it is difficult to reconcile! After all, one has to accept that things which are – to me – important aspects of my personal life, simply do no hold worth outside my home-relationships. The advent of a gig economy – think Facebook, Airbnb and other more flexible professions – has not fundamentally changed public policy, even as they outpace it.

For that reason alone, Bhutan is a model working eco-system. My first exposure to Bhutan was before I visited it. A Japanese colleague had traded in lucrative job at McKinsey in Tokyo to work with the Bhutanese authorities, helping them design and implement the Gross Happiness Index (GHI).

The idea was to develop measurable indicators as to the value of life. Each time the population is asked questions, their life style and habits are taken into consideration: how often they participate in community activities, visit family, commune and pray in temples, engage in spiritual retreat?

In this concept, GDP counts, but it is only one factor taken into consideration. Happiness arises not just from workers’ productivity but from their sense of community and the quality of their lives. The fact that these indicators can be quantified, measured as ‘worth,’ means that people think about them differently. Just making people aware of how to think of issues is important to start the debate.

And frankly it’s time for that. I work in a multicultural environment in the US where people routinely complain about South Asian and Middle Eastern men taking longer to catch up on political correctness and how to treat women colleagues. I bristle at the thought of my compatriots being culturally deficient until I remember my own experiences at work over two decades. It was always the desi male middle-age colleagues who would ask me whether I was taking a half-day when I would log off to feed a three month-old baby One particular repeat offender would also give five minute breaks to female assistants for bathroom breaks and then wonder why they had been away for longer. The European and American colleagues were actually supportive and encouraging –particularly as they had wives or mothers who were in the same situation. My anecdotes are unfortunately not unique – ask any women you know who works and you shall hear similar narratives.That kind of chauvinistic behavior is outdated and unacceptable, regardless of the cultural context. We may laugh it off as eccentricity but when the person holds a position of power, then this kind of behaviour sets the worst kind of example of toxic masculinity.

Now, I am older and more tempered. I have ready responses on now how to deal with behaviour like that. Early on in my career, I was constantly trying to prove myself (like most working mothers). It was hard enough performing, managing and juggling it all without being micromanaged as to your use of time. Conversely, it was often the lives of these colleagues who would wonder why their husbands kept very late hours, unaware that their better halves spent half the day playing squash, having long ‘business’ lunches and reading online newspapers at work. I smiled when they complained about their husband’s working hours, when I would witness how much “leisure” time their husbands spent at work.

Being in the office was considered “work”; leisure such as childcare and home responsibilities were relegated to the women a home. Men “baby sit” their kids, mothers parent them. We give kudos to men for being involved or hands-on with their children but take the same for granted when done by a mother. Even the language one uses can demean the woman’s contribution to the family partly as its considered invisible work which has no monetary value – though clearly the societal value is priceless. It is critical to leave our children with caring givers, important for us to have teachers who support our children in learning as it is important for them to see positivity in doing household work. To keep things going, it’s often the woman who plays the Chief Admin Officer of a family – whether remembering doctors’ appointments, planning school play dates or whether to go out or not. Some go as far to receive “pocket money” from their husbands, if they are not financially independent.

When taught about game theory and the sense of public good, it is very clear that we need to do better as a society about things that have value and use language and practice to support that belief. Many of the 21st-century issues – whether gender, climate, race, technology – will require a fundamental rethink of what the impact is for both men and women. It will mean recalibrating our assumptions. Our values matter only if they also embrace equity, fairness and a sense of empathy. Demeaning women, whether in the home or as a sitting Prime Minister, will not lead to a better outcome for society as a whole.

Leadership, use of appropriate language and behaviour – all of these matter. And that has been proved over centuries by a middle-aged man who did understand both value and worth very well indeed: Adam Smith!