Muslims in the Subcontinent have generally looked to Arabia, Iran and Afghanistan for their roots. Many claim to be Syeds, Qureshis, Siddiquis, Alavis, Mughals, Khans, Mirs etc. - all associated with these countries. For many centuries, Persian was the official language, and Arabic and Urdu were taken to be the mark of an educated Muslim. Most of the Islamic revival movements and institutions in colonial times were centred in Northern India, such as Deoband, Firangi Mahal, Tablighi Jamaat (started in Mewat) and the Aligarh movement of Sir Syed. The geography of these cultural movements has had a strong imprint on Muslim identity in the Subcontinent. The regional cultures and languages, such as Sindhi, Bengali or Gujarati, were viewed with the suspicion of being contaminated by Hindu idioms and beliefs.

The political struggle for independence further tied Muslim identity with Urdu, Punjabi and the North Indian cultures. Bengali Muslims have been stereotyped as having been influenced by Hindus’ interests. These notions contributed eventually to the break-up of Pakistan in 1971.

This stereotype could not be further from the truth. A new and engrossing book by Professor Mohammad Rashiduzzaman entitled Identity of a Muslim family in colonial Bengal. Between memories and history (New York: Peter Lang, 2021), provides an eye-opening account of the social history of Muslim Bengalis in the countryside around Dhaka. Dr. Rashiduzzaman, a professor at Dhaka University in the 1960s (moved to the US in the ‘70s), is the celebrated author of many books and articles on politics and history of the independence movement, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

This book is of a different genre. It gives a bottom-up view of the social life of Muslims in rural Bengal, their feelings, relations with Hindus and long struggle to advance administratively, politically, and educationally. He has built the story of Bengali Muslims’ identity around the life history of the three generations of his own family spanning more than a century (1847-1971). Rashiduzzaman’s instincts as a social scientist led him to seek confirmatory evidence of his memories and family accounts from various literary and historical writings. All in all, he offers a very illuminating and credible narrative of the social life of Muslims in rural Bengal.

His story of Muslim Bengalis’ identity begins with his grandfather (1847-1912) who grew up in the hangover of the lost Mughal rule and fall of Muslims’ power. The striking fact is that Muslim Bengalis’ reaction to their changed circumstances was the same as in the rest of India, namely withdrawal, resistance to the modern education and losing economically and administratively in competition with Hindus.

Bengal is a densely populated land of big rivers and small land holdings. Muslims were small farmers, often indebted to Hindu money lenders and economically a depressed community. Rashiduzzaman’s grandfather sold milk, was a small moneylender and grower of rice and jute on a few Bighas of land. Most land rent collectors were Hindus, as were an overwhelming majority of public officials. In rural society, they were the Bhadralok (gentry). Among Muslims, the remnants of Mughal aristocracy, who prided in their Persian-Afghan ancestry, formed a thin layer of upper strata, but had little power. This social structure of Muslim Bengal recapitulated the Muslims’ social situation across India.

Bengali Muslims began to be aware of their political and educational handicaps in the early 20th century. Leaving aside the political history, the book brings out early stirrings of Muslims’ pursuit of modern education, a share in administrative positions and political representation.

Rashiduzzaman’s father obtained a B.A degree after becoming a schoolteacher . The author rose to be a professor at Dacca University. Muslims advanced both educationally and occupationally in the modern idioms with the colonial government’s small incentives. Introduction of jute brought cash for Muslim peasants and small farmers, which contributed to their economic advancement. These broader social changes gradually built the base for Muslims’ progress and nationalist aspirations.

Muslim-Hindu relations in Bengal had all the patterns of closeness and distance between the two communities living side by side for centuries. The folk cultures of the two communities had many common elements: shared local legends, affinity for spiritualism, folk beliefs about ghosts, jinn, spirits, and music. Their religious paths were different but the search for experiential connection with the Higher Being were parallel. Rashiduzzaman writes about Bauls, Faqirs and Sadhus, who found shelter in their outer house in their wanderings and indulged in singing under his grandfather’s and latter father’s hospitality. They recited Sunban Panthis, Saiful Mulluk and Manjis’ (boatmen) songs with equal fervour. Yet his virtuous grandmother, though catering to her husband’ s proclivities, often admonished him to call a maulvi and ask for forgiveness. His father also was drawn to Sufi thoughts and had continuous discussions on the fine points of Sharia and Marafat with a friend called Rezu Chacha, a frequent visitor in their home.

The organized religion of both communities tends to be pietistic and moralizing, emphasizing differences of beliefs, strictness of observances and influenced by puritanical movements of varying intensity, like Ahl-Hadith and Deobandis among Muslims. Rashiduzzaman particularly points out that the Hindu custom of Choi-na-Choi (touch and not touch) was a source of Muslims resentment. There was periodic violence even in villages of good neighbourly relations, arising from such customs.

What l want to emphasize is that it reflected fully the dialectics of relations between the two communities all over India. At a personal and folk level, there was much intermingling. Yet formalized religious discourse had deep differences and competing political interests. As a child of some awareness, I experienced similar human closeness and communal distance from Hindus in our inner Lahore neighbourhoods. Muslim Bengalis’ experiences seem to be no different from what was happening in Punjab or UP. These differences were woven into Muslim Bengalis’ identity.

Bengali Muslims’ identity found expression in dress also. Rashiduzzaman’s father took up wearing the Sherwani and Fez cap in line with the custom of the rising middle-class Muslims, influenced by the Khalifat movement. Among the farmers and peasants, the Hindu-Muslim difference was symbolized by the Muslim Lungi, ‘a piece of cloth sewn in a circle like a Sarong’ and Dhoti that Hindus wore by tucking one end in the back. Women of both faiths mostly wore saris. Of course, both communities shared the love of the Bengali language, though there was a dialect that was called Muslim Bangla. Yet the Devanagari script of Bengali was viewed in Pakistan as a mark of Hindu influence.

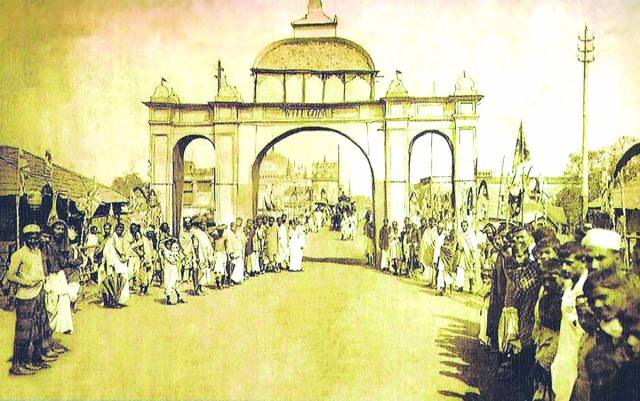

Bengali Muslims had a foretaste of the later partition in 1905, when Bengal was divided into Muslim east Bengal with Dhaka as the capital and Hindu west Bengal centred on Calcutta. They rejoiced in the new political power, expecting “their boys to get jobs”. Dhaka university was a product of this partition. The split lasted six years and had to be undone on the demands of Calcutta capitalists. It is not an accident that A.K Fazalul Haq, Bengal’s first premier in 1937, was a sponsor of the Pakistan Resolution. He subscribed to the notion “never apologize to be a Muslim”.

This book clears the stereotypes about Bengali Muslims forged in Pakistan to neutralize their demographic majority. Though distinct from Punjabis and Upites. they were equally affected by India’s political and religious movements and sentiments. In this sense, Bengali Muslims, now Bangladeshis, were in the mainstream of Muslim identity. Yet they were alienated by the political maneuverings of the undivided Pakistan. Prof.Rashiduzzaman has done a great service in writing from the ground a social history of Bengali’s Muslims. It is very difficult from the usual upper-atmospheric account of the politics of independence.

The political struggle for independence further tied Muslim identity with Urdu, Punjabi and the North Indian cultures. Bengali Muslims have been stereotyped as having been influenced by Hindus’ interests. These notions contributed eventually to the break-up of Pakistan in 1971.

This stereotype could not be further from the truth. A new and engrossing book by Professor Mohammad Rashiduzzaman entitled Identity of a Muslim family in colonial Bengal. Between memories and history (New York: Peter Lang, 2021), provides an eye-opening account of the social history of Muslim Bengalis in the countryside around Dhaka. Dr. Rashiduzzaman, a professor at Dhaka University in the 1960s (moved to the US in the ‘70s), is the celebrated author of many books and articles on politics and history of the independence movement, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

This book is of a different genre. It gives a bottom-up view of the social life of Muslims in rural Bengal, their feelings, relations with Hindus and long struggle to advance administratively, politically, and educationally. He has built the story of Bengali Muslims’ identity around the life history of the three generations of his own family spanning more than a century (1847-1971). Rashiduzzaman’s instincts as a social scientist led him to seek confirmatory evidence of his memories and family accounts from various literary and historical writings. All in all, he offers a very illuminating and credible narrative of the social life of Muslims in rural Bengal.

His story of Muslim Bengalis’ identity begins with his grandfather (1847-1912) who grew up in the hangover of the lost Mughal rule and fall of Muslims’ power. The striking fact is that Muslim Bengalis’ reaction to their changed circumstances was the same as in the rest of India, namely withdrawal, resistance to the modern education and losing economically and administratively in competition with Hindus.

Bengal is a densely populated land of big rivers and small land holdings. Muslims were small farmers, often indebted to Hindu money lenders and economically a depressed community. Rashiduzzaman’s grandfather sold milk, was a small moneylender and grower of rice and jute on a few Bighas of land. Most land rent collectors were Hindus, as were an overwhelming majority of public officials. In rural society, they were the Bhadralok (gentry). Among Muslims, the remnants of Mughal aristocracy, who prided in their Persian-Afghan ancestry, formed a thin layer of upper strata, but had little power. This social structure of Muslim Bengal recapitulated the Muslims’ social situation across India.

At a personal and folk level, there was much intermingling. Yet formalized religious discourse had deep differences and competing political interests

Bengali Muslims began to be aware of their political and educational handicaps in the early 20th century. Leaving aside the political history, the book brings out early stirrings of Muslims’ pursuit of modern education, a share in administrative positions and political representation.

Rashiduzzaman’s father obtained a B.A degree after becoming a schoolteacher . The author rose to be a professor at Dacca University. Muslims advanced both educationally and occupationally in the modern idioms with the colonial government’s small incentives. Introduction of jute brought cash for Muslim peasants and small farmers, which contributed to their economic advancement. These broader social changes gradually built the base for Muslims’ progress and nationalist aspirations.

Muslim-Hindu relations in Bengal had all the patterns of closeness and distance between the two communities living side by side for centuries. The folk cultures of the two communities had many common elements: shared local legends, affinity for spiritualism, folk beliefs about ghosts, jinn, spirits, and music. Their religious paths were different but the search for experiential connection with the Higher Being were parallel. Rashiduzzaman writes about Bauls, Faqirs and Sadhus, who found shelter in their outer house in their wanderings and indulged in singing under his grandfather’s and latter father’s hospitality. They recited Sunban Panthis, Saiful Mulluk and Manjis’ (boatmen) songs with equal fervour. Yet his virtuous grandmother, though catering to her husband’ s proclivities, often admonished him to call a maulvi and ask for forgiveness. His father also was drawn to Sufi thoughts and had continuous discussions on the fine points of Sharia and Marafat with a friend called Rezu Chacha, a frequent visitor in their home.

The organized religion of both communities tends to be pietistic and moralizing, emphasizing differences of beliefs, strictness of observances and influenced by puritanical movements of varying intensity, like Ahl-Hadith and Deobandis among Muslims. Rashiduzzaman particularly points out that the Hindu custom of Choi-na-Choi (touch and not touch) was a source of Muslims resentment. There was periodic violence even in villages of good neighbourly relations, arising from such customs.

What l want to emphasize is that it reflected fully the dialectics of relations between the two communities all over India. At a personal and folk level, there was much intermingling. Yet formalized religious discourse had deep differences and competing political interests. As a child of some awareness, I experienced similar human closeness and communal distance from Hindus in our inner Lahore neighbourhoods. Muslim Bengalis’ experiences seem to be no different from what was happening in Punjab or UP. These differences were woven into Muslim Bengalis’ identity.

Bengali Muslims’ identity found expression in dress also. Rashiduzzaman’s father took up wearing the Sherwani and Fez cap in line with the custom of the rising middle-class Muslims, influenced by the Khalifat movement. Among the farmers and peasants, the Hindu-Muslim difference was symbolized by the Muslim Lungi, ‘a piece of cloth sewn in a circle like a Sarong’ and Dhoti that Hindus wore by tucking one end in the back. Women of both faiths mostly wore saris. Of course, both communities shared the love of the Bengali language, though there was a dialect that was called Muslim Bangla. Yet the Devanagari script of Bengali was viewed in Pakistan as a mark of Hindu influence.

Bengali Muslims had a foretaste of the later partition in 1905, when Bengal was divided into Muslim east Bengal with Dhaka as the capital and Hindu west Bengal centred on Calcutta. They rejoiced in the new political power, expecting “their boys to get jobs”. Dhaka university was a product of this partition. The split lasted six years and had to be undone on the demands of Calcutta capitalists. It is not an accident that A.K Fazalul Haq, Bengal’s first premier in 1937, was a sponsor of the Pakistan Resolution. He subscribed to the notion “never apologize to be a Muslim”.

This book clears the stereotypes about Bengali Muslims forged in Pakistan to neutralize their demographic majority. Though distinct from Punjabis and Upites. they were equally affected by India’s political and religious movements and sentiments. In this sense, Bengali Muslims, now Bangladeshis, were in the mainstream of Muslim identity. Yet they were alienated by the political maneuverings of the undivided Pakistan. Prof.Rashiduzzaman has done a great service in writing from the ground a social history of Bengali’s Muslims. It is very difficult from the usual upper-atmospheric account of the politics of independence.