Situated 35 kilometers northwest of the city of Mansehra, the scenic town of Shergarh once served as the summer capital of the Nawabs of Amb, the oldest of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s four princely states. Hidden from the millions of domestic tourists who transit through Mansehra towards the northern areas each summer, Shergarh Fort is an exciting destination for travelers wishing to go off the beaten track to discover Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa’s art, history, architecture and cultural heritage.

The Shergarh Fort was built shortly after the region was captured by Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s military commanders Diwan Bhawani Das and Mir Singh in 1819. They wanted to block the western routes used by the Afghan Durranis to access Kashmir. At Shergarh, both empires met an unlikely adversary in the form of Painda Khan Tanoli, the fiercely independent minded chief of the Hindwal Tanoli tribe that inhabited Hazara’s trans-Indus Tanawal hills. As early as 1829, at the peak of the Lahore Durbar’s might, a visitor (Shah Ismail Dehlavi) to the region found Painda Khan’s military commanders already in control of the Sikh fort at Shergarh. Situated near the town of Shergarh are several battlefields where Painda Khan Tanoli, later described by colonial commentators as “a sort of wild man at war with all around him”, spent a major part of his life fighting not only the famed Sikh general Hari Singh Nalwa and the Afghan governor Azim Khan Durrani, but also the militant commander Syed Ahmed Barelvi. In the 1870s, Painda Khan’s grandson Nawab Muhammad Akram Khan transformed the inner quarters at Shergarh Fort into a Haveli for residential living.

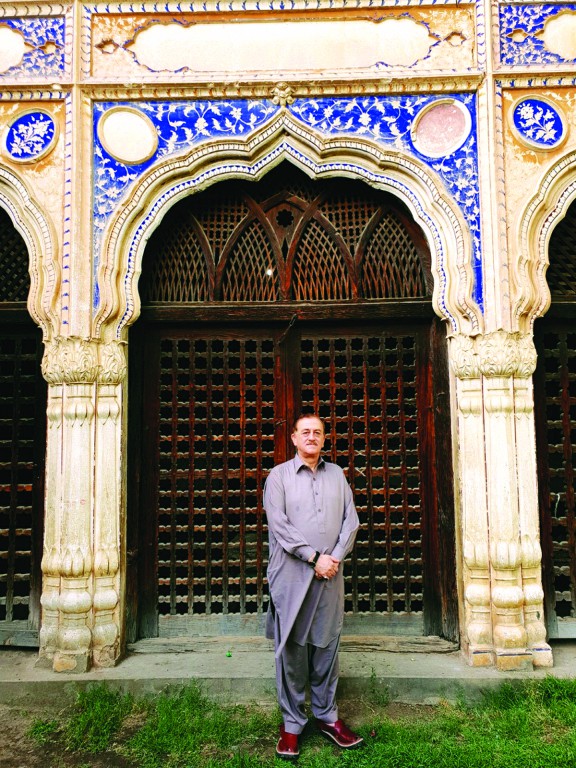

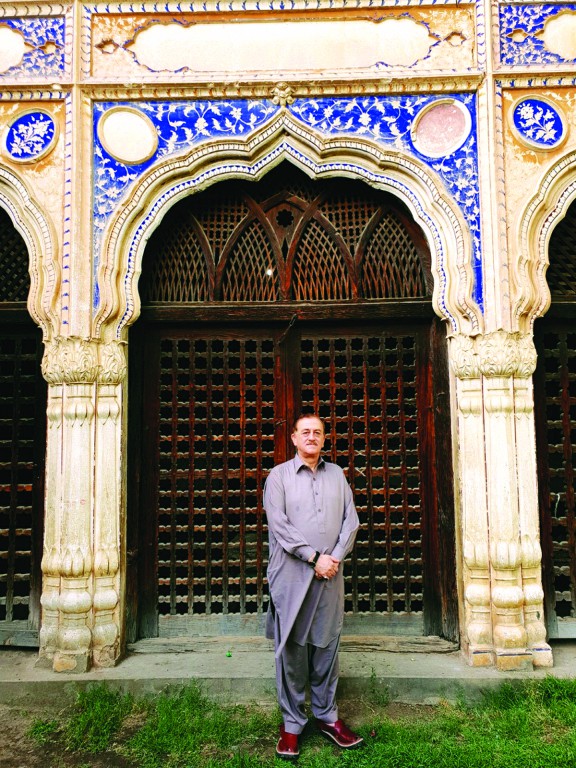

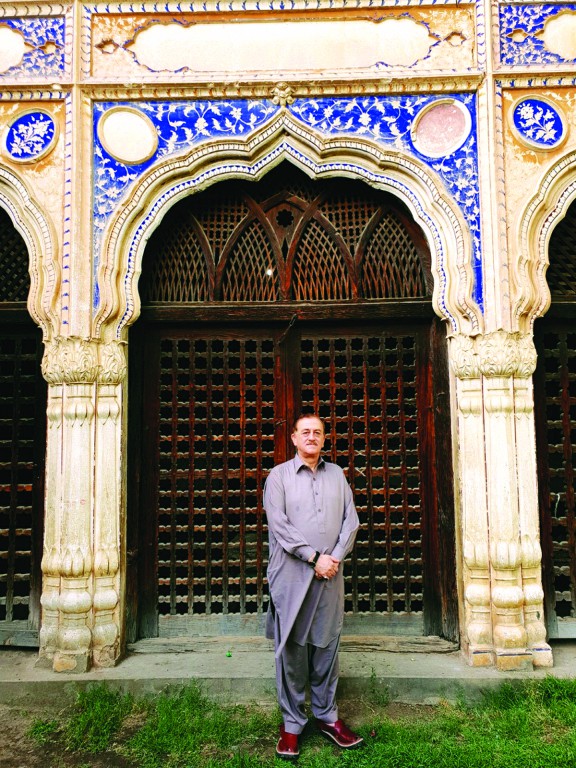

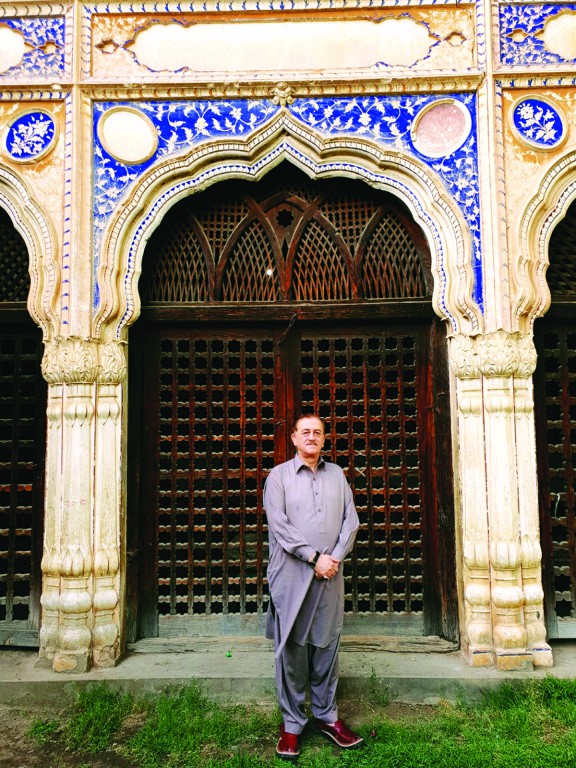

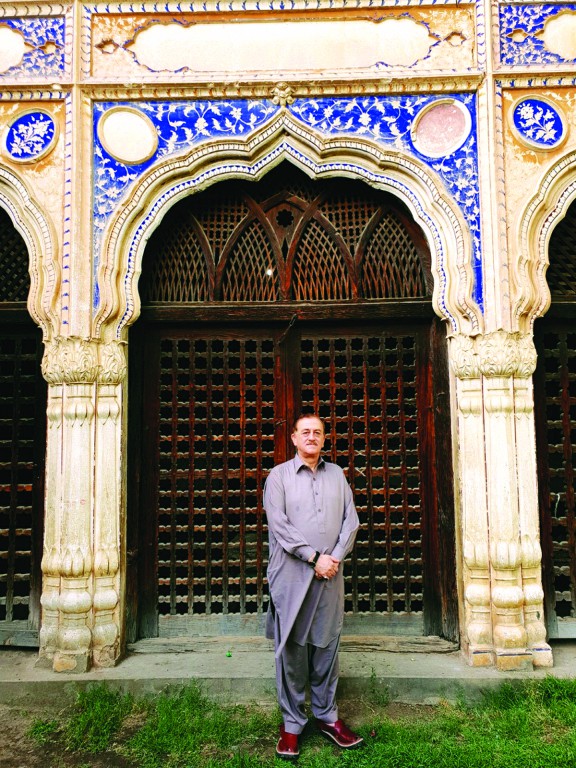

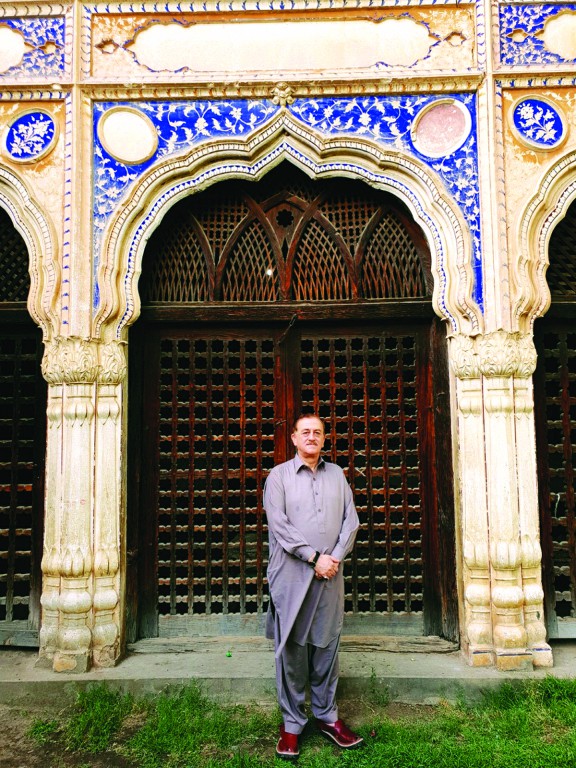

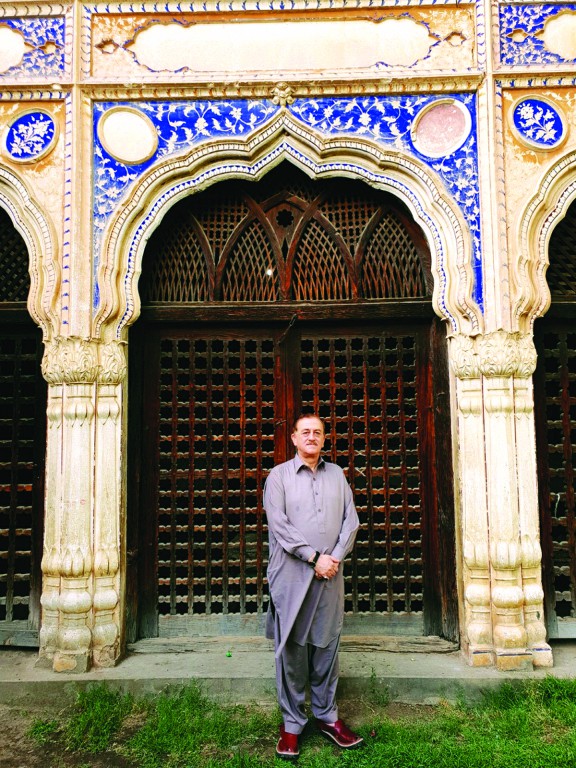

The northern face of the Haveli’s inner courtyard is richly decorated with fresco art and features fine examples of Himalayan architecture and woodwork. As it is used as a residence by the Nawab of Amb’s family, access to this inner courtyard is only granted to visitors on request. Other than floral motifs, the fresco art depicts fruits, crockery and items of day to day use. A tea set painted over an arching doorway could be evidence that the fresco artwork was made in the colonial period.

Art and woodwork in two richly decorated rooms in the Haveli can be compared in quality to adornments in Lahore’s popular Haveli Naunihal Singh and Peshawar’s Sethi House. According to Amb family’s oral traditions the lime plaster on the haveli’s walls was strengthened using unique ingredients like eggs and horsehair.

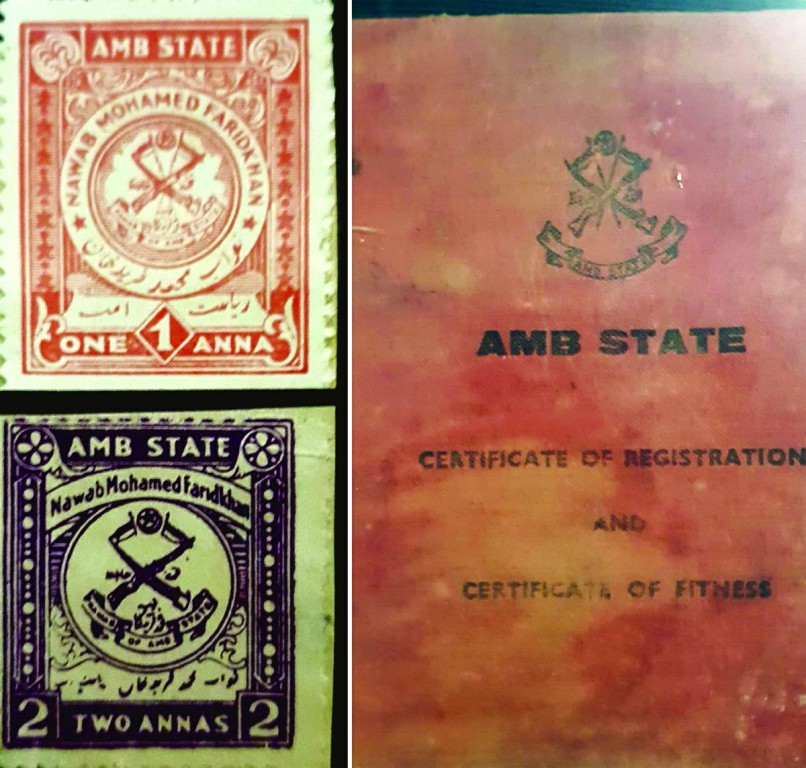

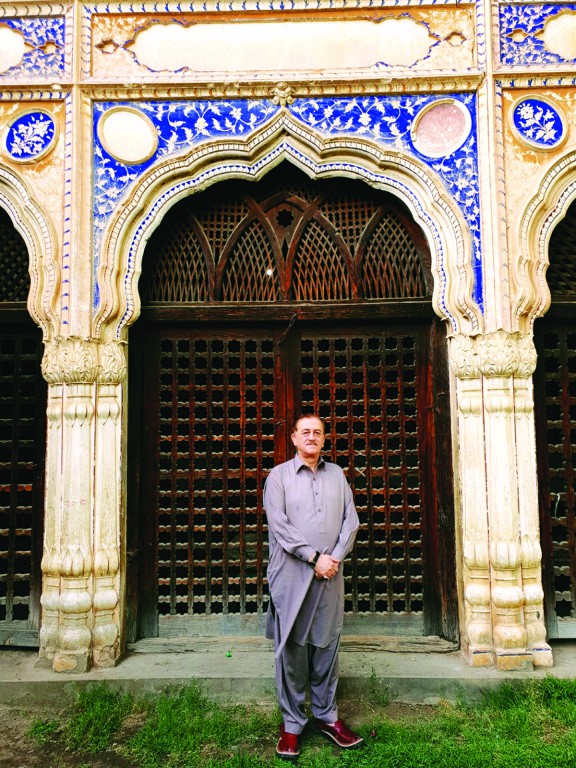

A room in the fort contains sacks full of administrative documents dating to the time when Amb State functioned as a semi-independent principality under British India and later Pakistan with an army comprising 6-8,000 active-duty servicemen and 15-20,000 tribal volunteers. Items of interest include Amb State’s car registration booklets, postal stamps, court archives, armoury information, revenue records and correspondences with colonial as well as Pakistani authorities including Mr. Jinnah. The records were haphazardly shifted to Shergarh when Amb was submerged by the building of the Tarbela Dam in the 1970s.

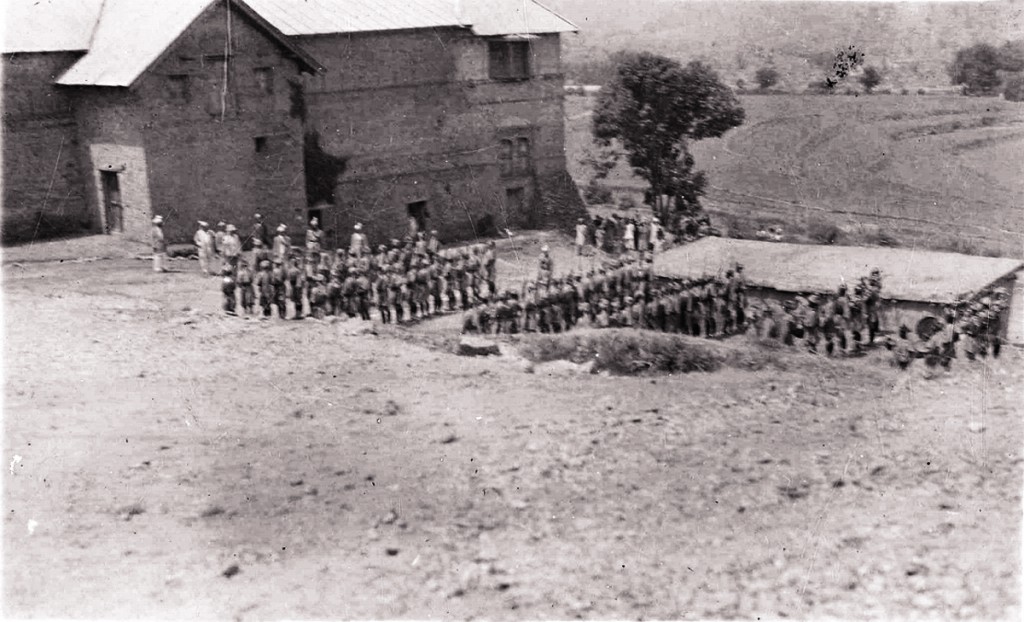

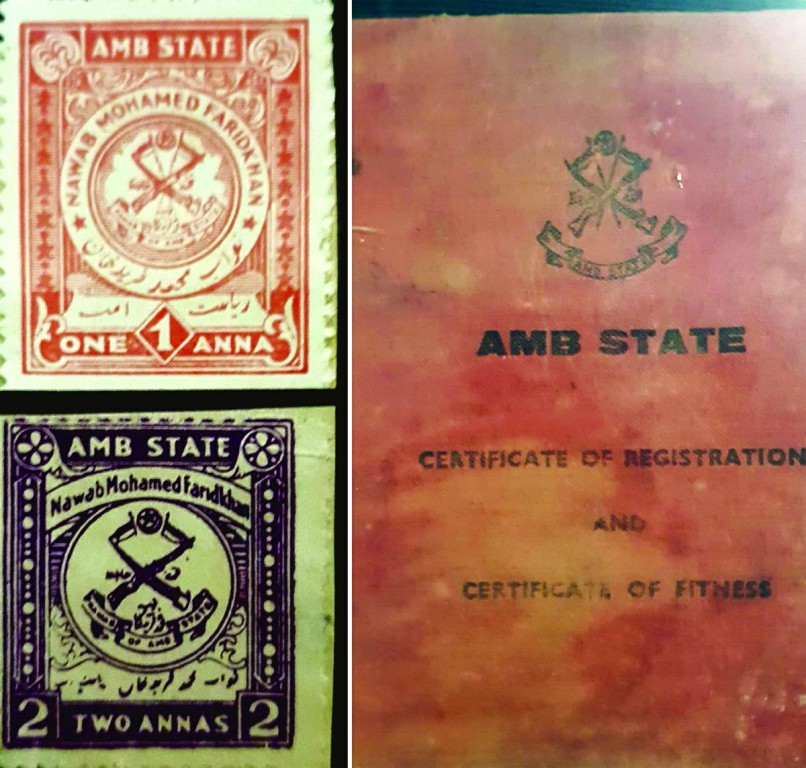

According to Nawabzada Jahangir Saeed, younger brother of the current titular Nawab of Amb, back in the day, the fort employed 300 full-time staff including those for cultural roles that are now obsolete. These included ‘Dedhibaans’ who guarded the fort’s private quarters, ‘Virsadaars’ in charge of hospitality and ‘Naghaarchis’ who played kettledrums to signal important occasions such as the announcement of Eid, welcoming guests and to announce the birth of a child. According to the Nawabzada, since the advent of the Soviet-Afghan war, the region’s time-honoured tradition of playing kettledrums has been replaced by aerial firing that puts lives at risk.

Plenty of elements in Shergarh Fort’s architecture can remind visitors of its origins as a military structure developed during Sikh rule two hundred years ago. The exterior walls are adorned by hundreds of embrasures that allowed guards stationed inside to fire on attackers in proximity. The fort’s massive wooden gates are reinforced through heavy bolts.

Two cannons built in Amb State during the earlier quarter of the nineteenth century adorn the front entrance of Shergarh Fort. Twenty-two cannons in use by the Amb State Army were handed over to the government of Pakistan when the state was merged with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in 1969. These are currently stationed outside various state guesthouses, messes and offices in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. In 2014, two of the cannons were returned to the original owners by the Government as recognition of their relevance to local heritage.

Other unique items of historical interest at Shergarh Fort include camel mounted swivel guns known locally as “zamburay.” The oldest of these Zamburay were used by Zabardast Khan, leader of the Tanoli tribe, alongside Ahmad Shah Abdali at the battle of Mathura in 1757.

The Shergarh Fort’s ‘Dera’ or visitors’ section was built in the 1920s during the reign of Nawab Khan e Zaman Khan. The Dera continues to serve a social function, as the Member of the Provincial Assembly (the current Nawab’s eldest son Nawabzada Farid Salahuddin) from the PK-33 constituency regularly convenes public meetings there. Unlike other princely states, most of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan’s former princely states have their roots in tribal chiefdoms that emerged during the downfall of the Mughal Empire. During the colonial era, the courts of these chiefdoms often paled in comparison to the opulence and grandeur of the wealthier princely states. However, they were relatively more egalitarian in nature, as the rulers often belonged to the same tribes as their subjects.

The Dera’s main meeting room features dozens of old photographs from the Amb family collection. Items of interest from the photo collection include a pre-partition photo of traditional flag bearers leading a tribal delegation that was visiting Shergarh. Known as “Nishaans”, the highly decorated flags that were used as markers of tribal and geographic identity have altogether vanished from public life in Hazara in the last few decades.

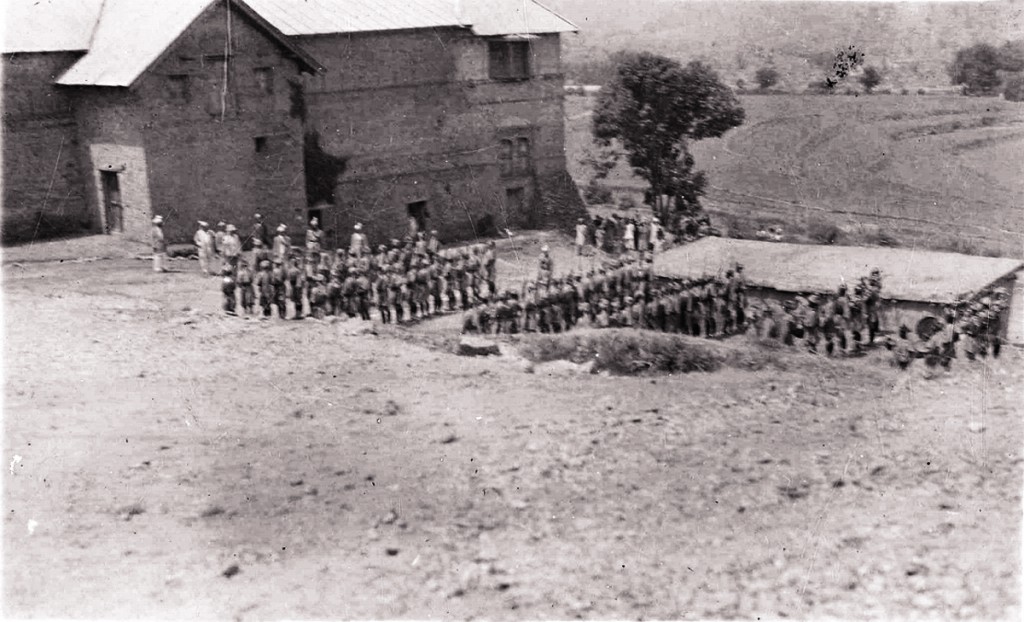

With princely states formally abolished in 1971, the Nawab’s family no longer has access to the revenues that financed the fort’s upkeep over the last two centuries. The catastrophic earthquake that struck Mansehra in October 2005 caused significant structural damage to the fort’s western walls that remains untreated to date. A discussion with Nawab Salahuddin Saeed, the current titular Nawab of Amb who was elected MNA from Mansehra five times between 1985 and 1999, reveals the interesting schisms between modernity and tradition that play out at Shergarh.

According to Nawab Salahuddin, “Though Shergarh’s doors are open to all visitors, building a hotel at Shergarh will not be viable as charging guests to stay at our home goes against our values. Shergarh needs to be respected as the last heritage landmark of the Tanoli tribe, which sacrificed ninety per cent of its heritage, wealth and property to the Tarbela Dam that submerged Amb State in the 1970s. Instead of a hotel, with the support of the government or international donors we would be happy to accommodate a museum in a section of the fort to introduce locals and tourists to Hazara’s rich culture and history.”

Recognizing Shergarh Fort’s relevance and shared importance to Sikh military history, in 2019 the Nawab of Amb’s family celebrated the fort’s two hundredth birthday with twenty Sikh friends from the USA and Singapore.

Famed across the world, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s rich military history spanning from Alexander the Great’s invasions to the local uprisings against colonial rule, can make it a fascinating destination for cultural tourism. However, most of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s historical forts continue to be off limits to tourists as they are in use by the military. The historic forts in possession of the royal families of the former Princely states of Chitral, Dir, Swat and Amb are alternate sites that are more accessible to the public and could be promising avenues for developing cultural tourism in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

The Shergarh Fort was built shortly after the region was captured by Maharaja Ranjit Singh’s military commanders Diwan Bhawani Das and Mir Singh in 1819. They wanted to block the western routes used by the Afghan Durranis to access Kashmir. At Shergarh, both empires met an unlikely adversary in the form of Painda Khan Tanoli, the fiercely independent minded chief of the Hindwal Tanoli tribe that inhabited Hazara’s trans-Indus Tanawal hills. As early as 1829, at the peak of the Lahore Durbar’s might, a visitor (Shah Ismail Dehlavi) to the region found Painda Khan’s military commanders already in control of the Sikh fort at Shergarh. Situated near the town of Shergarh are several battlefields where Painda Khan Tanoli, later described by colonial commentators as “a sort of wild man at war with all around him”, spent a major part of his life fighting not only the famed Sikh general Hari Singh Nalwa and the Afghan governor Azim Khan Durrani, but also the militant commander Syed Ahmed Barelvi. In the 1870s, Painda Khan’s grandson Nawab Muhammad Akram Khan transformed the inner quarters at Shergarh Fort into a Haveli for residential living.

The northern face of the Haveli’s inner courtyard is richly decorated with fresco art and features fine examples of Himalayan architecture and woodwork. As it is used as a residence by the Nawab of Amb’s family, access to this inner courtyard is only granted to visitors on request. Other than floral motifs, the fresco art depicts fruits, crockery and items of day to day use. A tea set painted over an arching doorway could be evidence that the fresco artwork was made in the colonial period.

Art and woodwork in two richly decorated rooms in the Haveli can be compared in quality to adornments in Lahore’s popular Haveli Naunihal Singh and Peshawar’s Sethi House. According to Amb family’s oral traditions the lime plaster on the haveli’s walls was strengthened using unique ingredients like eggs and horsehair.

A room in the fort contains sacks full of administrative documents dating to the time when Amb State functioned as a semi-independent principality under British India and later Pakistan with an army comprising 6-8,000 active-duty servicemen and 15-20,000 tribal volunteers. Items of interest include Amb State’s car registration booklets, postal stamps, court archives, armoury information, revenue records and correspondences with colonial as well as Pakistani authorities including Mr. Jinnah. The records were haphazardly shifted to Shergarh when Amb was submerged by the building of the Tarbela Dam in the 1970s.

According to Nawabzada Jahangir Saeed, younger brother of the current titular Nawab of Amb, back in the day, the fort employed 300 full-time staff including those for cultural roles that are now obsolete. These included ‘Dedhibaans’ who guarded the fort’s private quarters, ‘Virsadaars’ in charge of hospitality and ‘Naghaarchis’ who played kettledrums to signal important occasions such as the announcement of Eid, welcoming guests and to announce the birth of a child. According to the Nawabzada, since the advent of the Soviet-Afghan war, the region’s time-honoured tradition of playing kettledrums has been replaced by aerial firing that puts lives at risk.

Plenty of elements in Shergarh Fort’s architecture can remind visitors of its origins as a military structure developed during Sikh rule two hundred years ago. The exterior walls are adorned by hundreds of embrasures that allowed guards stationed inside to fire on attackers in proximity. The fort’s massive wooden gates are reinforced through heavy bolts.

According to the Nawabzada, since the advent of the Soviet-Afghan war, the region’s time-honoured tradition of playing kettledrums has been replaced by aerial firing that puts lives at risk

Two cannons built in Amb State during the earlier quarter of the nineteenth century adorn the front entrance of Shergarh Fort. Twenty-two cannons in use by the Amb State Army were handed over to the government of Pakistan when the state was merged with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in 1969. These are currently stationed outside various state guesthouses, messes and offices in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. In 2014, two of the cannons were returned to the original owners by the Government as recognition of their relevance to local heritage.

Other unique items of historical interest at Shergarh Fort include camel mounted swivel guns known locally as “zamburay.” The oldest of these Zamburay were used by Zabardast Khan, leader of the Tanoli tribe, alongside Ahmad Shah Abdali at the battle of Mathura in 1757.

The Shergarh Fort’s ‘Dera’ or visitors’ section was built in the 1920s during the reign of Nawab Khan e Zaman Khan. The Dera continues to serve a social function, as the Member of the Provincial Assembly (the current Nawab’s eldest son Nawabzada Farid Salahuddin) from the PK-33 constituency regularly convenes public meetings there. Unlike other princely states, most of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan’s former princely states have their roots in tribal chiefdoms that emerged during the downfall of the Mughal Empire. During the colonial era, the courts of these chiefdoms often paled in comparison to the opulence and grandeur of the wealthier princely states. However, they were relatively more egalitarian in nature, as the rulers often belonged to the same tribes as their subjects.

The Dera’s main meeting room features dozens of old photographs from the Amb family collection. Items of interest from the photo collection include a pre-partition photo of traditional flag bearers leading a tribal delegation that was visiting Shergarh. Known as “Nishaans”, the highly decorated flags that were used as markers of tribal and geographic identity have altogether vanished from public life in Hazara in the last few decades.

With princely states formally abolished in 1971, the Nawab’s family no longer has access to the revenues that financed the fort’s upkeep over the last two centuries. The catastrophic earthquake that struck Mansehra in October 2005 caused significant structural damage to the fort’s western walls that remains untreated to date. A discussion with Nawab Salahuddin Saeed, the current titular Nawab of Amb who was elected MNA from Mansehra five times between 1985 and 1999, reveals the interesting schisms between modernity and tradition that play out at Shergarh.

According to Nawab Salahuddin, “Though Shergarh’s doors are open to all visitors, building a hotel at Shergarh will not be viable as charging guests to stay at our home goes against our values. Shergarh needs to be respected as the last heritage landmark of the Tanoli tribe, which sacrificed ninety per cent of its heritage, wealth and property to the Tarbela Dam that submerged Amb State in the 1970s. Instead of a hotel, with the support of the government or international donors we would be happy to accommodate a museum in a section of the fort to introduce locals and tourists to Hazara’s rich culture and history.”

Recognizing Shergarh Fort’s relevance and shared importance to Sikh military history, in 2019 the Nawab of Amb’s family celebrated the fort’s two hundredth birthday with twenty Sikh friends from the USA and Singapore.

Famed across the world, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s rich military history spanning from Alexander the Great’s invasions to the local uprisings against colonial rule, can make it a fascinating destination for cultural tourism. However, most of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s historical forts continue to be off limits to tourists as they are in use by the military. The historic forts in possession of the royal families of the former Princely states of Chitral, Dir, Swat and Amb are alternate sites that are more accessible to the public and could be promising avenues for developing cultural tourism in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.