Take away a person’s language and you not only snatch away their identity, but you leave them lost and confused.

It is common knowledge that Punjabis are most populous ethno-linguistic group in Pakistan, and inevitably, the most visible and represented in the echelons of power, be it politics, military or the bureaucracy. However, unlike other communities, we Punjabis are perhaps the only ones in Pakistan who do not speak their own regional language. Before going further: let it be clarified that the issue being addressed here is focused solely on the urban educated, middle class and onwards segment of society.

Simply ask yourself, if you are a Punjabi millennial and you live in an urban city like Lahore, when was the last time you conversed in Punjabi with your parents, your O/A-levels teachers or your boss? While there are definitely exceptions where the parents make it a point to encourage Punjabi, but the fact remains that majority of our urban dwellers communicate in either Urdu or English. The sad reality is that the only occasion when we speak Punjabi is to communicate with a shopkeeper or domestic help. At most, Punjabi may be employed as an effective tool to curse someone or cracking a joke at another.

The root cause for this reluctance to speak Punjabi can be traced to our history. One of the unifying factors in South Asian Muslims’ struggle for independence was the Urdu language, which set them apart from Hindus and other communities. In Punjab, Muslims and Sikhs spoke a common language, Punjabi. The Muslims of Punjab decided to distinguish themselves from the Sikh community, and adopted Urdu in order to align with the Pakistan movement. This singular act would sow the seeds of division within Punjabi society, as the elites began embracing Urdu to set themselves apart from the common people. In this way, the Punjabi language was relegated to the rural and illiterate folk, and a linguistically classist society emerged, where speaking Urdu became a sign of sophistication and being ‘educated’.

Today, Punjabi is not taught either in Urdu- or English-medium schools. As a result, the present generation is completely ignorant of the culture and traditions of the land, so much so that any person speaking Punjabi is referred to by the derogatory slang, “paindu”. There are in fact universities that annually celebrate a “Paindu Day”, where students dress up as what they imagine are rural Punjabi-speaking people – and in doing so, cheerfully mock and ridicule their own culture.

By way of comparison to the urban Punjabi’s attitude to their mother tongue, consider, for instance, that a Pashtun – whether he/she is a judge, banker, medical student, business tycoon or gardener – will always converse with fellow Pashtuns in Pashto. Urdu will only be used where necessary.

Similarly, our Punjabi counterparts across the border, especially the Sikhs, take pride in speaking Punjabi, irrespective of their social standing. Even the Sikhs born and raised in Canada or England know and converse proudly in perfect Punjabi. This creates a sense of unity within the community, and reduces classism.

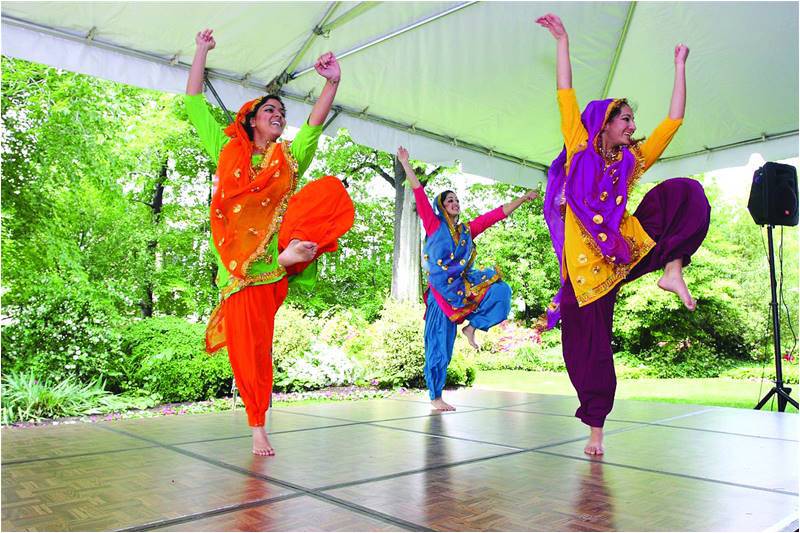

But this is not simply about the mode of communication; there is a pervasive ignorance amongst the young population of the overall culture of Punjab. Take traditional dance for example. On every festive occasion, you will see our Pashtun brethren performing beautiful synchronized attan, which is a traditional celebratory dance of Pakhtunkhwa. However, in Punjab, one hardly ever witnesses boys and girls properly performing the luddi dance, which is apparently too embarrassing. Instead, we see people jumping around on Bollywood movie songs. Similarly, apparel is another way of exhibiting one’s culture; each region in Pakistan has its own distinctive cap. While the people of other provinces display their caps with pride – whether in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Sindh or Gilgit-Baltistan – it would appear that Punjabis are sadly the only ones to have consigned the traditional pagri (turban) to marriage ceremonies alone. Pre-Partition pictures of students at different educational institutions, such as Government College Lahore or MAO College Lahore, show that wearing the pagri was a must on every formal event or gathering. Today, however, apart from Lahore’s Aitchison College, no other school or college (public or private) promotes the pagri, which has been ‘relegated’ to gate-keepers and court staff.

In the same vein, every year, Sindh celebrates its culture through the Sindhi Cultural Day, when politicians, students and people from all walks of life across the province wear traditional apparel such as the ajrak with great fervour. Seminars and events are held where Sindhi history and culture are discussed. Unfortunately, no such day is celebrated in Punjab.

For such abysmal state of affairs, one has to put some blame on our parents’ generation. In the rat race for good grades and jobs, they encouraged their children to become fluent in Urdu and English, but, sadly, did not teach them to love their Punjabi roots and traditions. This is why at any social gathering in Lahore, one can witness parents and elderly talking in Punjabi, while the children may be seen conversing amongst themselves in English.

The media also shoulders some responsibility in this regard. Punjabi cinema, instead of depicting the true richness and elegance of Punjab, promoted a culture of violence and lewdness, thereby further distancing the educated classes from the language. Moreover, in television dramas and theatre, the role of the Punjabi speaker is to usually to evoke laughter, as they are portrayed as unsophisticated and reckless. Additionally, social media

influencers, who have a massive fan following, usually present Punjabi-speaking characters in their skits as silly and illiterate. This promotes the narrative that educated and well-to-do people only converse in Urdu/English, whereas Punjabi is only spoken by the lower classes.

In order to support Punjabi speaking amongst the youth, all segments of society – the provincial government, educational institutions, media houses and most importantly, parents – have to start promoting and conversing in the language. This means ensuring that a child is taught Punjabi with the same zeal as Urdu and English. At schools (both private and public), teaching Punjabi as a regional language should be made compulsory. Furthermore, the depiction of Punjabi language on film and television needs to be corrected, so that the youth can see their role models proudly speaking Punjabi on public forums.

Hence, it is only when Punjabi re-appears in our drawing rooms, offices and classrooms, that will we be able to rid our younger generation of the stigmas presently attached to this rich and beautiful language.

It is common knowledge that Punjabis are most populous ethno-linguistic group in Pakistan, and inevitably, the most visible and represented in the echelons of power, be it politics, military or the bureaucracy. However, unlike other communities, we Punjabis are perhaps the only ones in Pakistan who do not speak their own regional language. Before going further: let it be clarified that the issue being addressed here is focused solely on the urban educated, middle class and onwards segment of society.

Simply ask yourself, if you are a Punjabi millennial and you live in an urban city like Lahore, when was the last time you conversed in Punjabi with your parents, your O/A-levels teachers or your boss? While there are definitely exceptions where the parents make it a point to encourage Punjabi, but the fact remains that majority of our urban dwellers communicate in either Urdu or English. The sad reality is that the only occasion when we speak Punjabi is to communicate with a shopkeeper or domestic help. At most, Punjabi may be employed as an effective tool to curse someone or cracking a joke at another.

The root cause for this reluctance to speak Punjabi can be traced to our history. One of the unifying factors in South Asian Muslims’ struggle for independence was the Urdu language, which set them apart from Hindus and other communities. In Punjab, Muslims and Sikhs spoke a common language, Punjabi. The Muslims of Punjab decided to distinguish themselves from the Sikh community, and adopted Urdu in order to align with the Pakistan movement. This singular act would sow the seeds of division within Punjabi society, as the elites began embracing Urdu to set themselves apart from the common people. In this way, the Punjabi language was relegated to the rural and illiterate folk, and a linguistically classist society emerged, where speaking Urdu became a sign of sophistication and being ‘educated’.

Today, Punjabi is not taught either in Urdu- or English-medium schools. As a result, the present generation is completely ignorant of the culture and traditions of the land, so much so that any person speaking Punjabi is referred to by the derogatory slang, “paindu”. There are in fact universities that annually celebrate a “Paindu Day”, where students dress up as what they imagine are rural Punjabi-speaking people – and in doing so, cheerfully mock and ridicule their own culture.

By way of comparison to the urban Punjabi’s attitude to their mother tongue, consider, for instance, that a Pashtun – whether he/she is a judge, banker, medical student, business tycoon or gardener – will always converse with fellow Pashtuns in Pashto. Urdu will only be used where necessary.

Similarly, our Punjabi counterparts across the border, especially the Sikhs, take pride in speaking Punjabi, irrespective of their social standing. Even the Sikhs born and raised in Canada or England know and converse proudly in perfect Punjabi. This creates a sense of unity within the community, and reduces classism.

But this is not simply about the mode of communication; there is a pervasive ignorance amongst the young population of the overall culture of Punjab. Take traditional dance for example. On every festive occasion, you will see our Pashtun brethren performing beautiful synchronized attan, which is a traditional celebratory dance of Pakhtunkhwa. However, in Punjab, one hardly ever witnesses boys and girls properly performing the luddi dance, which is apparently too embarrassing. Instead, we see people jumping around on Bollywood movie songs. Similarly, apparel is another way of exhibiting one’s culture; each region in Pakistan has its own distinctive cap. While the people of other provinces display their caps with pride – whether in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Sindh or Gilgit-Baltistan – it would appear that Punjabis are sadly the only ones to have consigned the traditional pagri (turban) to marriage ceremonies alone. Pre-Partition pictures of students at different educational institutions, such as Government College Lahore or MAO College Lahore, show that wearing the pagri was a must on every formal event or gathering. Today, however, apart from Lahore’s Aitchison College, no other school or college (public or private) promotes the pagri, which has been ‘relegated’ to gate-keepers and court staff.

In the same vein, every year, Sindh celebrates its culture through the Sindhi Cultural Day, when politicians, students and people from all walks of life across the province wear traditional apparel such as the ajrak with great fervour. Seminars and events are held where Sindhi history and culture are discussed. Unfortunately, no such day is celebrated in Punjab.

For such abysmal state of affairs, one has to put some blame on our parents’ generation. In the rat race for good grades and jobs, they encouraged their children to become fluent in Urdu and English, but, sadly, did not teach them to love their Punjabi roots and traditions. This is why at any social gathering in Lahore, one can witness parents and elderly talking in Punjabi, while the children may be seen conversing amongst themselves in English.

The media also shoulders some responsibility in this regard. Punjabi cinema, instead of depicting the true richness and elegance of Punjab, promoted a culture of violence and lewdness, thereby further distancing the educated classes from the language. Moreover, in television dramas and theatre, the role of the Punjabi speaker is to usually to evoke laughter, as they are portrayed as unsophisticated and reckless. Additionally, social media

influencers, who have a massive fan following, usually present Punjabi-speaking characters in their skits as silly and illiterate. This promotes the narrative that educated and well-to-do people only converse in Urdu/English, whereas Punjabi is only spoken by the lower classes.

In order to support Punjabi speaking amongst the youth, all segments of society – the provincial government, educational institutions, media houses and most importantly, parents – have to start promoting and conversing in the language. This means ensuring that a child is taught Punjabi with the same zeal as Urdu and English. At schools (both private and public), teaching Punjabi as a regional language should be made compulsory. Furthermore, the depiction of Punjabi language on film and television needs to be corrected, so that the youth can see their role models proudly speaking Punjabi on public forums.

Hence, it is only when Punjabi re-appears in our drawing rooms, offices and classrooms, that will we be able to rid our younger generation of the stigmas presently attached to this rich and beautiful language.