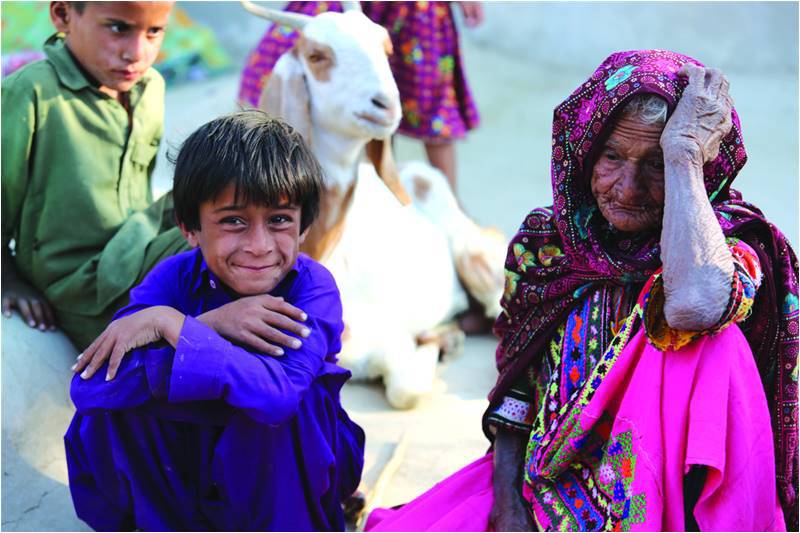

In this era of a global pandemic, when everyone seems itnent on securing their own life, who can spare time to think of the lives of deprived shelter-less nomadic tribes who have been wandering village to village and city to city in their own country and bearing the brunt of hard times for years? They have no homes, no villages and no cities as the basis for any residential identity. Any location where they build makeshift straw huts and stay for some days becomes their home.

They believe that wandering from one place to another is perhaps the very nature of life. For centuries they are en route – undertaking an unending journey. Certainly this contributed to the ease with which they have always been neglected and kept away from the fruits of development by every entity.

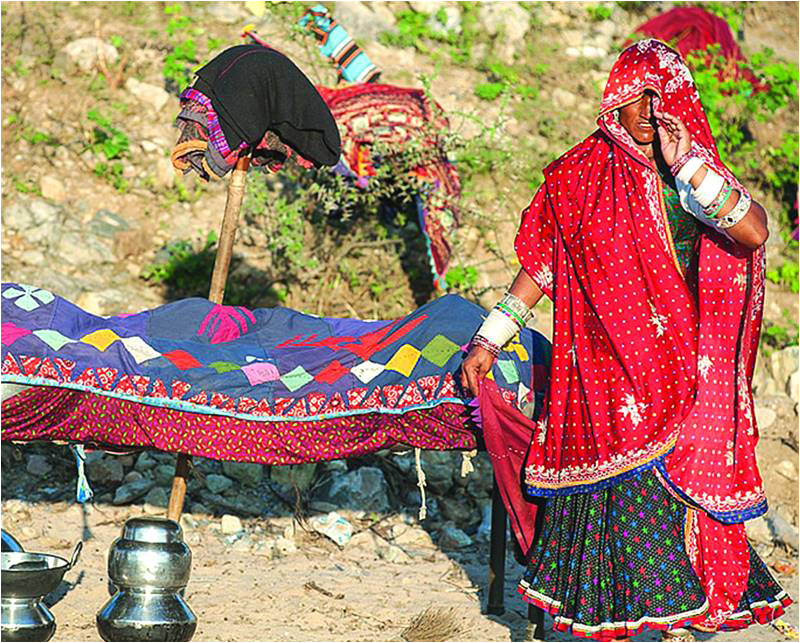

Governments provide education, healthcare, electricity, safe drinking water and other basic necessities of life to the people living in urban and rural settlements of the country but when it comes to offer the same facilities to the poor nomadic people, it is almost as if in the government’s eyes, they deserve no improvements. Their nomadic lifestyle makes it particularly difficult for them to find a space to live in megacities so that they can earn some bread and butter for their poverty stricken families. In the major urban centres, their home becomes the footpaths, ruined structures and less used corners underneath flyovers and along railway stations. The women mostly beg while men work as labourers or smalltime hawkers. Together, operating from the margins of cities, they try to fill the empty stomachs of their children. In small towns and villages they make straw huts along entry and exit points and adopt a similar mode of earning their livelihood. Most of the men and women of nomadic tribes sell handmade household items and childrens’ products in the nearby villages. When they feel that their earning has been reduced in one area, they start their journey to another place. The cycle of wandering drives their year.

Long before the 1947 Partition, even in the 19th century, when the British started taking over the Indian Subcontinent, the majority of the population in the Indo-Pak region used to live in rural areas. The rural settlements of that time were different from today, because there used to be jungles/forests and wilderness everywhere. A cluster of a few households within a jungle were called a village. The nomadic tribes used to live in the most thick jungles and they used to spend a prosperous and relaxed life with their families – at least by comparison to the existence that they eke out under contemporary conditions.

As British rule solidified over the Indian Subcontinent, the various nomadic tribes suffered more than other communities and tribes living in India, as they were considered “born criminals” by the colonial authorities. In 1871, the British government passed the Criminal Tribes Act with the intension to restrict all the activities of nomadic tribes and unfortunately it proved to be the last nail in the coffin of their prosperity.

As part of the implementation of the Criminal Tribes Act, vast tracts of forests were set on fire where these hapless tribes used to live. Thousands of them were hanged. Thousands were jailed for the rest of their lives. And those who became successful in escaping the fire and steel of the Empire had become absconders forever. Force into becoming fugitives by force of law, the never-ending wandering of nomadic tribes kicked off in the Subcontinent. It is a process which is still going on today.

Why were the British colonial authoties so hostile to the nomads? We are told that some among the nomadic tribes used to raid the caravans and camps of the British Army and rob their possessions. When such incidents increased in the India, the government decided to take revenge. The retribution of the colonial state was ruthless. In passing the Criminal Tribes Act, they declared around 300 tribes as habitual criminals. It was collective punishment on a mass scale, all across South Asia.

In their forced wanderings, some of these populations arrived in Pakistan around the time of the 1947 Partition. Soon after, the new borders of post-colonial South Asia kicked in.

In Sindh, wandering tribes are living for a long time and are often seen as indigenous people of this land. The iron fist of the colonial state and the prejudiced attitude of the local population forced them to live on the margins of society. The British themselves have left the Indian Subcontinent a long ago but the attitudes that they instilled in state and society remain prevalent – to the detriment of these tribes.

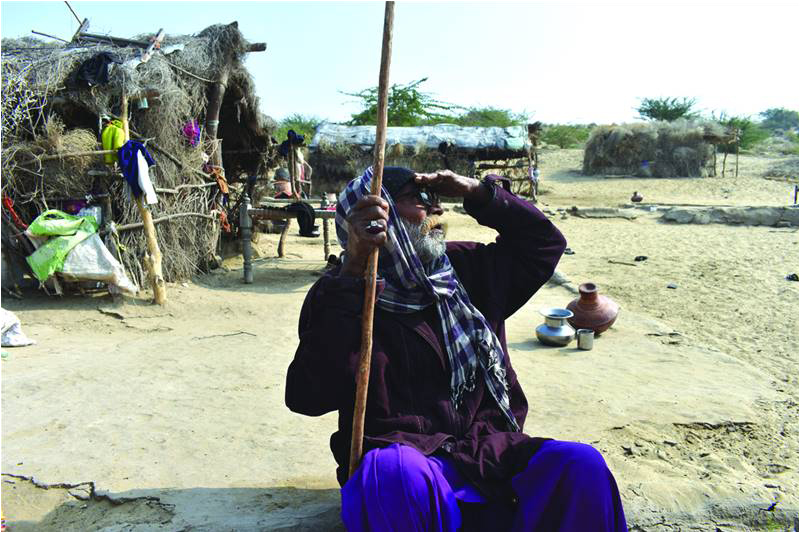

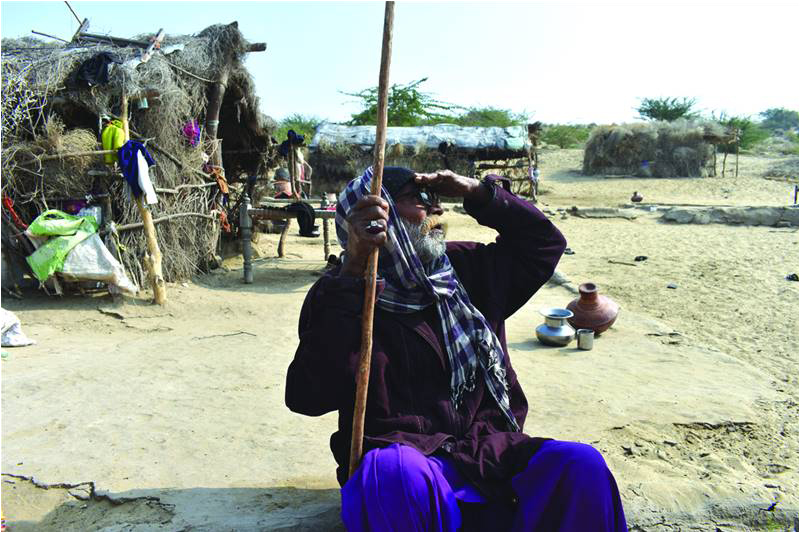

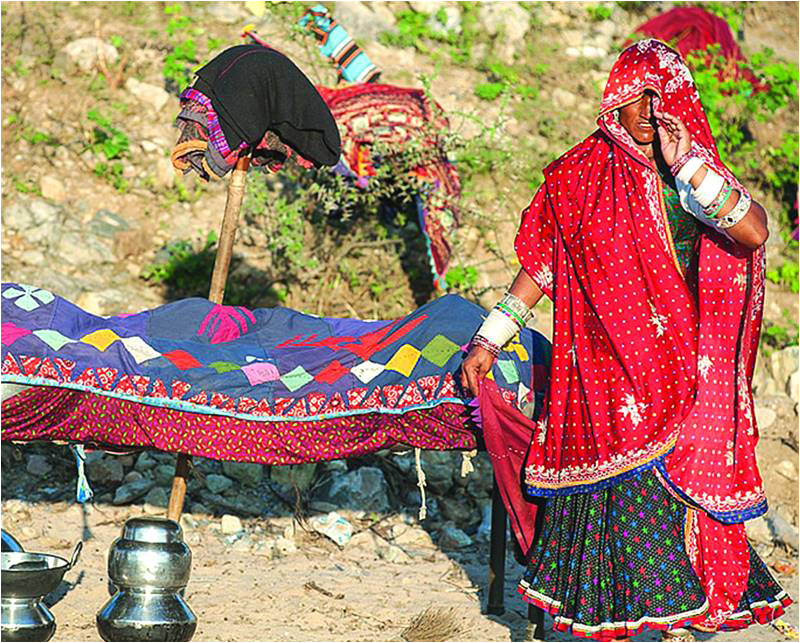

In the way of material posessions, many of these people have but one pair of clothes to wear on their bodies, one or two charpoys, some kitchenware items, a few quilts and a pet dog as their entire universe. Regardless of seasons and weathers they can be found along the roadside, in remote empty fields and somewhere on the road, traveling by donkey carts – wandering from one village to another.

Saansi, Koochra, Kobootra, Bharha and Shikari are the names of some nomadic tribes which have existed in Sindh for a long time. There are no permanent residential colonies where they can be settled and provided with some basic services. For them, it would be a great leap of progress if they simply get to live like millions of other Pakistani people – who, at least, have two meals a day to eat and a roof on their heads to feel secure.

The solution to bringing them out of the conditions imposed on them by the colonial state can only begin when the government begins to offer them housing colonies in every district of the country. Moreover a separate quota for the people belonging to such tribes in government jobs and educational institutions should also be fixed. The process of healing wounds of decades and uplifting them has to begin soon.

The writer is a freelance contributor and he can be reached at abbaskhaskheli110@gmail.com

They believe that wandering from one place to another is perhaps the very nature of life. For centuries they are en route – undertaking an unending journey. Certainly this contributed to the ease with which they have always been neglected and kept away from the fruits of development by every entity.

Governments provide education, healthcare, electricity, safe drinking water and other basic necessities of life to the people living in urban and rural settlements of the country but when it comes to offer the same facilities to the poor nomadic people, it is almost as if in the government’s eyes, they deserve no improvements. Their nomadic lifestyle makes it particularly difficult for them to find a space to live in megacities so that they can earn some bread and butter for their poverty stricken families. In the major urban centres, their home becomes the footpaths, ruined structures and less used corners underneath flyovers and along railway stations. The women mostly beg while men work as labourers or smalltime hawkers. Together, operating from the margins of cities, they try to fill the empty stomachs of their children. In small towns and villages they make straw huts along entry and exit points and adopt a similar mode of earning their livelihood. Most of the men and women of nomadic tribes sell handmade household items and childrens’ products in the nearby villages. When they feel that their earning has been reduced in one area, they start their journey to another place. The cycle of wandering drives their year.

Long before the 1947 Partition, even in the 19th century, when the British started taking over the Indian Subcontinent, the majority of the population in the Indo-Pak region used to live in rural areas. The rural settlements of that time were different from today, because there used to be jungles/forests and wilderness everywhere. A cluster of a few households within a jungle were called a village. The nomadic tribes used to live in the most thick jungles and they used to spend a prosperous and relaxed life with their families – at least by comparison to the existence that they eke out under contemporary conditions.

As British rule solidified over the Indian Subcontinent, the various nomadic tribes suffered more than other communities and tribes living in India, as they were considered “born criminals” by the colonial authorities. In 1871, the British government passed the Criminal Tribes Act with the intension to restrict all the activities of nomadic tribes and unfortunately it proved to be the last nail in the coffin of their prosperity.

In the major urban centres, their home becomes the footpaths, ruined structures and less used corners underneath flyovers and along railway stations

As part of the implementation of the Criminal Tribes Act, vast tracts of forests were set on fire where these hapless tribes used to live. Thousands of them were hanged. Thousands were jailed for the rest of their lives. And those who became successful in escaping the fire and steel of the Empire had become absconders forever. Force into becoming fugitives by force of law, the never-ending wandering of nomadic tribes kicked off in the Subcontinent. It is a process which is still going on today.

Why were the British colonial authoties so hostile to the nomads? We are told that some among the nomadic tribes used to raid the caravans and camps of the British Army and rob their possessions. When such incidents increased in the India, the government decided to take revenge. The retribution of the colonial state was ruthless. In passing the Criminal Tribes Act, they declared around 300 tribes as habitual criminals. It was collective punishment on a mass scale, all across South Asia.

In their forced wanderings, some of these populations arrived in Pakistan around the time of the 1947 Partition. Soon after, the new borders of post-colonial South Asia kicked in.

The retribution of the colonial state was ruthless. In passing the Criminal Tribes Act, they declared around 300 tribes as habitual criminals. It was collective punishment on a mass scale

In Sindh, wandering tribes are living for a long time and are often seen as indigenous people of this land. The iron fist of the colonial state and the prejudiced attitude of the local population forced them to live on the margins of society. The British themselves have left the Indian Subcontinent a long ago but the attitudes that they instilled in state and society remain prevalent – to the detriment of these tribes.

In the way of material posessions, many of these people have but one pair of clothes to wear on their bodies, one or two charpoys, some kitchenware items, a few quilts and a pet dog as their entire universe. Regardless of seasons and weathers they can be found along the roadside, in remote empty fields and somewhere on the road, traveling by donkey carts – wandering from one village to another.

Saansi, Koochra, Kobootra, Bharha and Shikari are the names of some nomadic tribes which have existed in Sindh for a long time. There are no permanent residential colonies where they can be settled and provided with some basic services. For them, it would be a great leap of progress if they simply get to live like millions of other Pakistani people – who, at least, have two meals a day to eat and a roof on their heads to feel secure.

The solution to bringing them out of the conditions imposed on them by the colonial state can only begin when the government begins to offer them housing colonies in every district of the country. Moreover a separate quota for the people belonging to such tribes in government jobs and educational institutions should also be fixed. The process of healing wounds of decades and uplifting them has to begin soon.

The writer is a freelance contributor and he can be reached at abbaskhaskheli110@gmail.com