As the Coronavirus continues to wreak havoc across the world, it makes sense, more than ever, to appreciate those who strive to make our world an easier place.

There are many from different fields of life putting themselves directly in harm’s way to protect or help heal those who need them. Amongst the many issues at hand is one of domestic violence.

An article in a Pakistani newspaper talks about how home is not a safe place for victims of domestic violence. Earlier on many of these victims found solace at work or a relative’s or friend’s house. But now they are quarantined with their ‘captor.’

Sadly these stories stretch across the globe and the aspect of such abuse has been around long before the virus struck our lives, but the present-day circumstances and threat of illness makes everything more complex. One call to a domestic violence hotline here in the U.S reported that a husband told his wife that he would throw here out into the street if she coughed.

Here in Seattle, some women of eastern origins find themselves caught between an alien culture and a sinister home environment. So what does one do without a mother’s or childhood friend’s home nearby?

And this is where Neelam Khaki comes in.

In search of inspiration in the Pacific north-west, I come across the impactful Neelam, creating a place of peace for her fellow women out here in Washington state. Neelam speaks softly but with strength. Her soulful demeanour comes coupled with a determination to improve the plight of those around her.

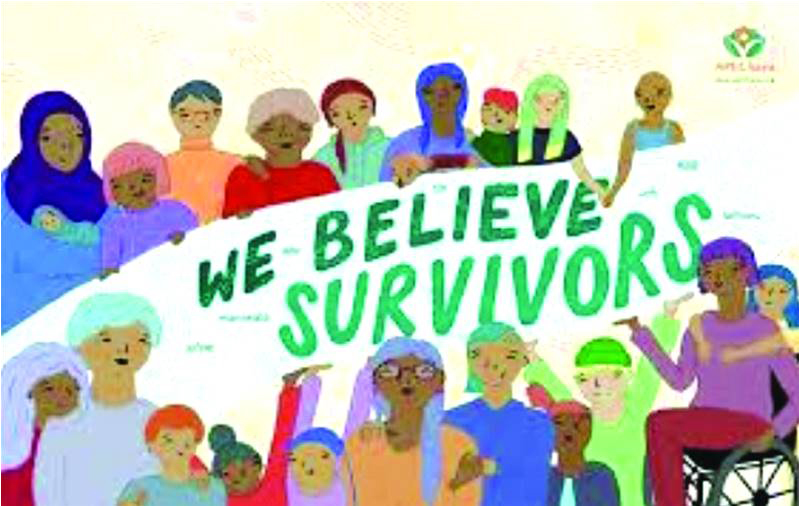

And this is how she does it: Neelam Khaki is the Peaceful Families Taskforce Coordinator at API Chaya, an organization serving South Asian, Middle Eastern and API survivors of domestic violence, sexual assault, and human trafficking.

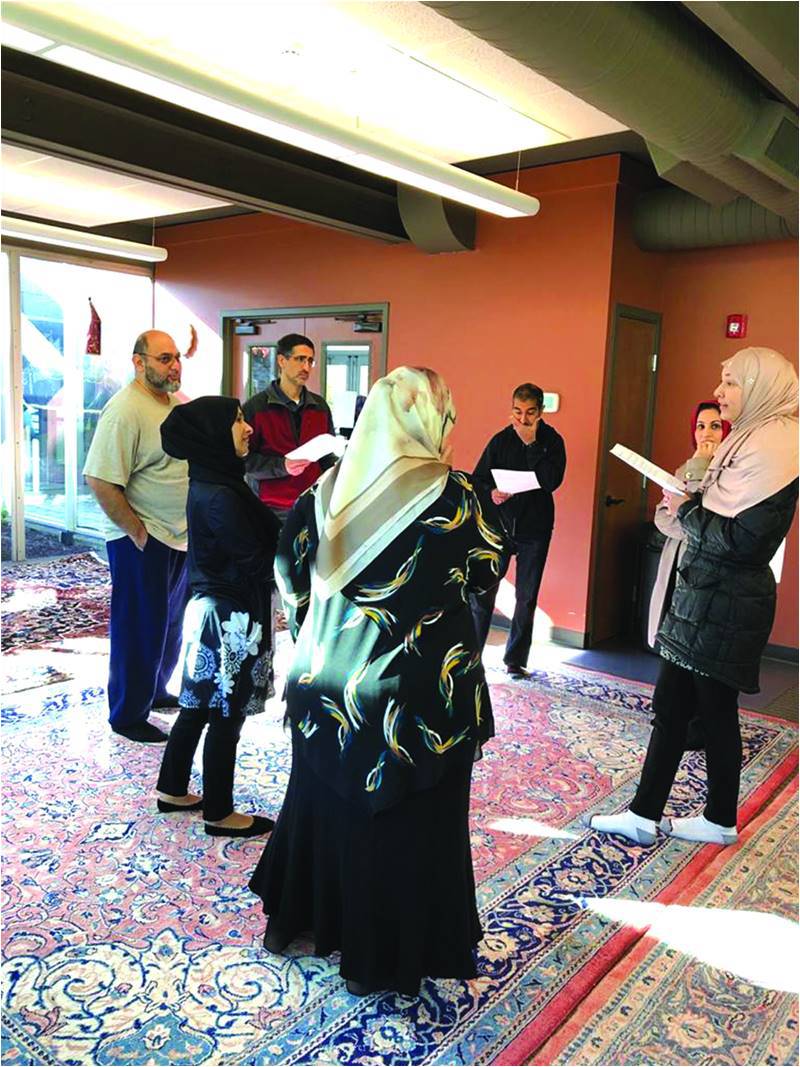

Her work within the PFT involves working with local Muslim communities to create peaceful families, by using the Qur’anic model of the family, through training, education and community engagement. Her current focus is on domestic violence prevention within faith-based communities.

Neelam is a graduate in LLB Laws from the London School of Economics, and completed the Legal Practice Course at the College of Law, London. Prior to moving to the U.S, she was employed at a London City law firm.

Zeinab Masud: How and where did your interest in social justice begin?

Neelam Khaki: My interest in social justice began in a voluntary capacity, whilst working for The Samaritans, a UK based organization supporting suicidal clients. I think I had always been interested in social justice. While we were growing up, we heard very firm views about how suicide was unforgivable in our religion.

While I accepted that, I also questioned this and found myself going into those darker areas.

Working with the Samaritans, I found how people could be bought back to a better place through active listening and empathy. It taught me to put aside judgment.

I went on to work with Lifewire as a helpline volunteer, supporting survivors in domestic violence situations, and later as a Court Appointed Special Advocate, supporting minors subject to dependency proceedings.

ZM: We live in a world stricken by judgement. Your work deals with Mosques and there is an influence of the yardstick which you experienced while you were growing up, strictly defined ideas of right and wrong. Yet you learnt to see people as individuals...

NK: I understood that their habits did not define them. That has really benefited me to this day,

to be able to see the whole person.

I grew up studying in a mainstream school in Britain with a lot of students outside my faith. I saw their struggles with drugs and alcohol.

I had had many High School friends who had gone through troubling experiences. I came to view people as needing support. I wanted to help.

ZM: What is API Chaya?

NK: There are two different organizations involved, API and Chaya. Both deal with domestic violence. Chahiya deals with the South Asian community. API deals with a parallel community, the Asian Pacific Islander Women and Family Safety Centre. Both deal with similar issues.

Some years ago, a survivor of domestic violence appeared in court in Seattle, seeking a protection order. She was accompanied by three friends. The abuser turned up with a gun and shot them all. One of the women had been pregnant. Each year API Chaya has a vigil. That’s where the idea of the Safety Centre came from.

After the merger we were able to pool our staff. I joined them in 2013. We also deal with Human Trafficking. We serve people from varied backgrounds. We don’t believe in turning anyone away.

My particular project involves the Muslim community. That’s where our faith based work takes place. We have relationships with a couple of churches and are trying to build a relationship with the Gurudwara. We believe in working towards different faiths. There are many things we have in common. We do our best to be inclusive.

ZM: Is it easier (relatively) for victims of abuse from our part of the world (Pakistan, India, etc) to be here in Washington State? Or would they have been better off in their home countries?

ZM: Is it easier (relatively) for victims of abuse from our part of the world (Pakistan, India, etc) to be here in Washington State? Or would they have been better off in their home countries?

NK: We know from research that when people move countries, that can be a trigger for abuse.

Survivors often feel that if they were back home then it would be easier to tolerate the abuse as they would have extended family nearby. Here it’s often just the nuclear family. That was one of the reasons for Chaya being formed as a support system.

As we form trust between communities, it becomes possible to rephrase some of the ideas they have around violence. The idea is to try and separate cultural beliefs from Islamic teachings.

Ironically while we live in a secular country, we are able to discover what Islam truly is.

So, while the move is a trigger, it is also a chance to have older, implemented ideas reframed. They are deprived of old support systems but have also been able to shed old stereotypical ideas.

It is important to uphold beliefs but we offer them alternatives ie they have been taught to put up with beatings but haven’t realized that Prophet (SAW) never raised his hand on a woman and he felt that the best of people were those who never raised a hand on their wives. To get a broader perspective of Islam is very important and helpful.

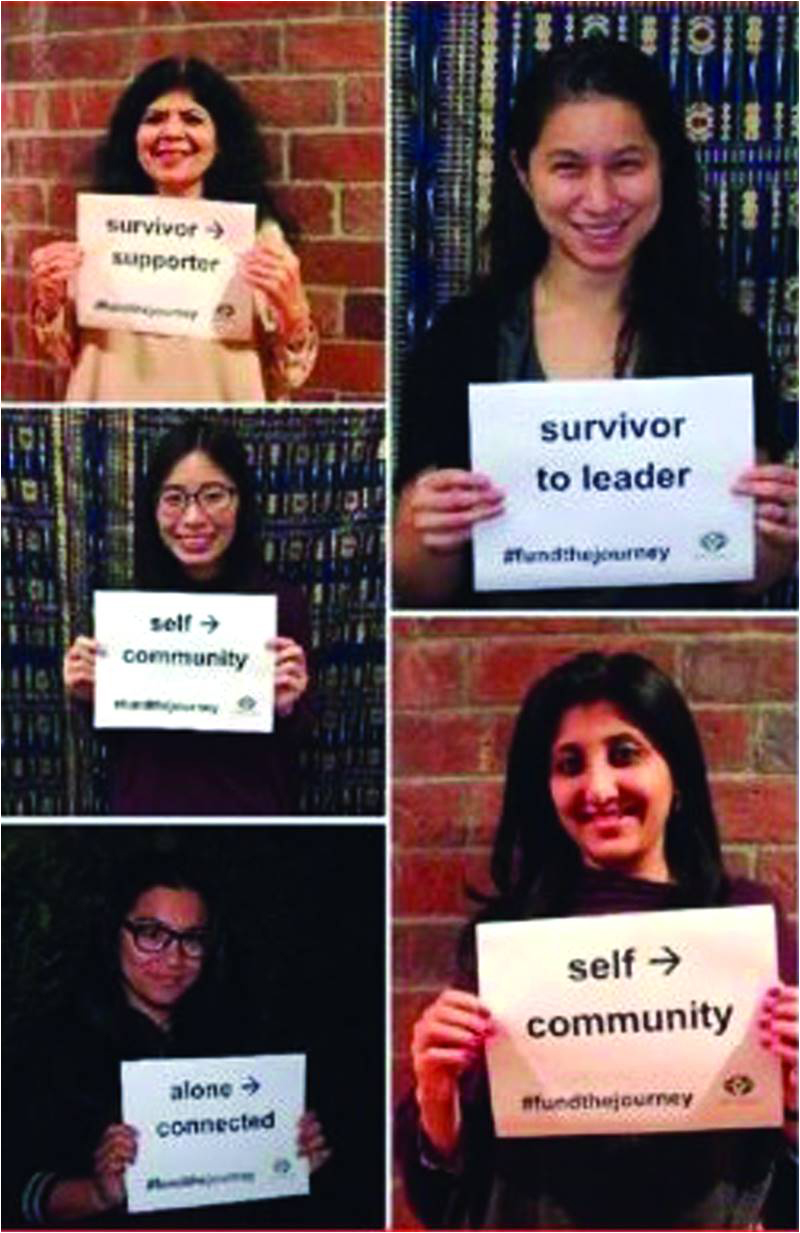

We do our best to validate the survivor’s experience, Educate them about the cycle of violence so that they understand the pattern that grips them. They shouldn’t feel that they have a duty to forgive and forget.

ZM: Has there been a change in the mindset of men out there, an influence on the male psyche, during your experience at API Chaya?

NK: When our work initially started, women would say that they had gone to the Imam and not felt supported. The fact is however that there is a lot of diversity amongst the Imams.

We then set up training sessions for the Imams. They were very receptive. I really admire them because many of them came here as immigrants without an earlier awareness regarding the support needed by community members here. However they were very receptive to the training they received. I hold them in high esteem for that.

ZM: What strong aspects of womanhood have you seen in your work?

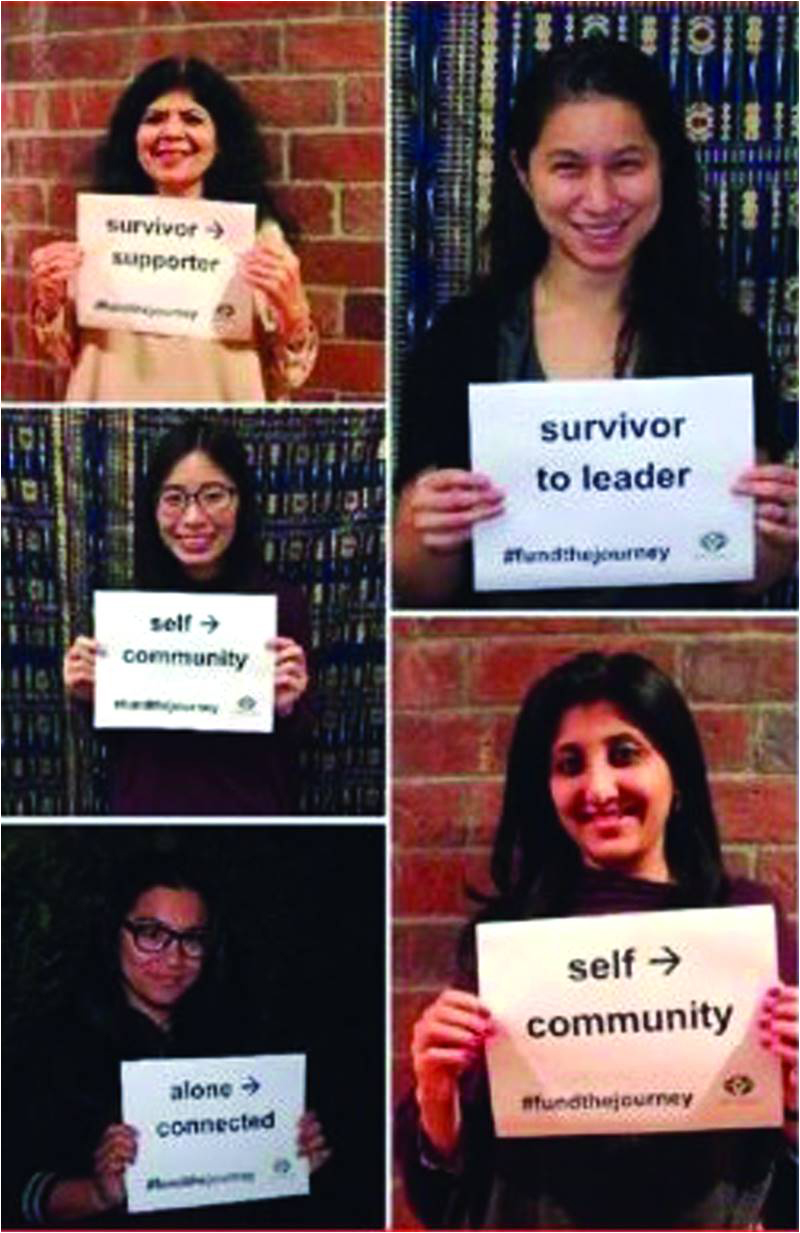

NK: I’ve seen a lot of growth. There are women who came here as immigrants completely dependent on their husbands. I have seen them reach a point when they are ready to move on from abusive relationships in a relatively short period of time.

Someone who couldn’t drive, had never worked was now living away from her abuser, still managing to be a good mother, still retaining that gentleness and dignity.

We are there to validate their experience.

ZM: What makes you a strong woman?

NK: (without hesitation) My mother. She raised me as a single mother in the 1980’s when in our community that was still considered a stigma.

She always held her head up high and stood behind her decisions.

She has been my greatest confidante and supporter. My mother empowered me.

I would like to say that one of the reasons my work is so dear to my heart is because it provides me the opportunity to live my faith. Whilst ritual and doctrine are deeply rooted within me, what excites and inspires me is to apply religious teaching to one’s life and work in a way that is dynamic and meaningful.

There are many from different fields of life putting themselves directly in harm’s way to protect or help heal those who need them. Amongst the many issues at hand is one of domestic violence.

An article in a Pakistani newspaper talks about how home is not a safe place for victims of domestic violence. Earlier on many of these victims found solace at work or a relative’s or friend’s house. But now they are quarantined with their ‘captor.’

Sadly these stories stretch across the globe and the aspect of such abuse has been around long before the virus struck our lives, but the present-day circumstances and threat of illness makes everything more complex. One call to a domestic violence hotline here in the U.S reported that a husband told his wife that he would throw here out into the street if she coughed.

Here in Seattle, some women of eastern origins find themselves caught between an alien culture and a sinister home environment. So what does one do without a mother’s or childhood friend’s home nearby?

And this is where Neelam Khaki comes in.

“The idea is to try and separate cultural beliefs from Islamic teachings. Ironically while we live in a secular country, we are able to discover what Islam truly is”

In search of inspiration in the Pacific north-west, I come across the impactful Neelam, creating a place of peace for her fellow women out here in Washington state. Neelam speaks softly but with strength. Her soulful demeanour comes coupled with a determination to improve the plight of those around her.

And this is how she does it: Neelam Khaki is the Peaceful Families Taskforce Coordinator at API Chaya, an organization serving South Asian, Middle Eastern and API survivors of domestic violence, sexual assault, and human trafficking.

Her work within the PFT involves working with local Muslim communities to create peaceful families, by using the Qur’anic model of the family, through training, education and community engagement. Her current focus is on domestic violence prevention within faith-based communities.

Neelam is a graduate in LLB Laws from the London School of Economics, and completed the Legal Practice Course at the College of Law, London. Prior to moving to the U.S, she was employed at a London City law firm.

Zeinab Masud: How and where did your interest in social justice begin?

Neelam Khaki: My interest in social justice began in a voluntary capacity, whilst working for The Samaritans, a UK based organization supporting suicidal clients. I think I had always been interested in social justice. While we were growing up, we heard very firm views about how suicide was unforgivable in our religion.

While I accepted that, I also questioned this and found myself going into those darker areas.

Working with the Samaritans, I found how people could be bought back to a better place through active listening and empathy. It taught me to put aside judgment.

I went on to work with Lifewire as a helpline volunteer, supporting survivors in domestic violence situations, and later as a Court Appointed Special Advocate, supporting minors subject to dependency proceedings.

ZM: We live in a world stricken by judgement. Your work deals with Mosques and there is an influence of the yardstick which you experienced while you were growing up, strictly defined ideas of right and wrong. Yet you learnt to see people as individuals...

NK: I understood that their habits did not define them. That has really benefited me to this day,

to be able to see the whole person.

I grew up studying in a mainstream school in Britain with a lot of students outside my faith. I saw their struggles with drugs and alcohol.

I had had many High School friends who had gone through troubling experiences. I came to view people as needing support. I wanted to help.

ZM: What is API Chaya?

NK: There are two different organizations involved, API and Chaya. Both deal with domestic violence. Chahiya deals with the South Asian community. API deals with a parallel community, the Asian Pacific Islander Women and Family Safety Centre. Both deal with similar issues.

Some years ago, a survivor of domestic violence appeared in court in Seattle, seeking a protection order. She was accompanied by three friends. The abuser turned up with a gun and shot them all. One of the women had been pregnant. Each year API Chaya has a vigil. That’s where the idea of the Safety Centre came from.

After the merger we were able to pool our staff. I joined them in 2013. We also deal with Human Trafficking. We serve people from varied backgrounds. We don’t believe in turning anyone away.

My particular project involves the Muslim community. That’s where our faith based work takes place. We have relationships with a couple of churches and are trying to build a relationship with the Gurudwara. We believe in working towards different faiths. There are many things we have in common. We do our best to be inclusive.

ZM: Is it easier (relatively) for victims of abuse from our part of the world (Pakistan, India, etc) to be here in Washington State? Or would they have been better off in their home countries?

ZM: Is it easier (relatively) for victims of abuse from our part of the world (Pakistan, India, etc) to be here in Washington State? Or would they have been better off in their home countries?NK: We know from research that when people move countries, that can be a trigger for abuse.

Survivors often feel that if they were back home then it would be easier to tolerate the abuse as they would have extended family nearby. Here it’s often just the nuclear family. That was one of the reasons for Chaya being formed as a support system.

As we form trust between communities, it becomes possible to rephrase some of the ideas they have around violence. The idea is to try and separate cultural beliefs from Islamic teachings.

Ironically while we live in a secular country, we are able to discover what Islam truly is.

So, while the move is a trigger, it is also a chance to have older, implemented ideas reframed. They are deprived of old support systems but have also been able to shed old stereotypical ideas.

It is important to uphold beliefs but we offer them alternatives ie they have been taught to put up with beatings but haven’t realized that Prophet (SAW) never raised his hand on a woman and he felt that the best of people were those who never raised a hand on their wives. To get a broader perspective of Islam is very important and helpful.

We do our best to validate the survivor’s experience, Educate them about the cycle of violence so that they understand the pattern that grips them. They shouldn’t feel that they have a duty to forgive and forget.

ZM: Has there been a change in the mindset of men out there, an influence on the male psyche, during your experience at API Chaya?

NK: When our work initially started, women would say that they had gone to the Imam and not felt supported. The fact is however that there is a lot of diversity amongst the Imams.

We then set up training sessions for the Imams. They were very receptive. I really admire them because many of them came here as immigrants without an earlier awareness regarding the support needed by community members here. However they were very receptive to the training they received. I hold them in high esteem for that.

ZM: What strong aspects of womanhood have you seen in your work?

NK: I’ve seen a lot of growth. There are women who came here as immigrants completely dependent on their husbands. I have seen them reach a point when they are ready to move on from abusive relationships in a relatively short period of time.

Someone who couldn’t drive, had never worked was now living away from her abuser, still managing to be a good mother, still retaining that gentleness and dignity.

We are there to validate their experience.

ZM: What makes you a strong woman?

NK: (without hesitation) My mother. She raised me as a single mother in the 1980’s when in our community that was still considered a stigma.

She always held her head up high and stood behind her decisions.

She has been my greatest confidante and supporter. My mother empowered me.

I would like to say that one of the reasons my work is so dear to my heart is because it provides me the opportunity to live my faith. Whilst ritual and doctrine are deeply rooted within me, what excites and inspires me is to apply religious teaching to one’s life and work in a way that is dynamic and meaningful.