Ali Kazim is among Pakistan’s most dynamic visual artists. A highly talented person, Kazim is also a ‘brave’ artist because unlike many from his fold, he is willing to take risks. A number of artists after having reached a good level of success are reluctant to move beyond their known or established style. Given the competitive and limited art market, artists do not want to risk their already achieved success or clientele. But Ali Kazim is audacious enough to build on his creative prowess and continues to amaze the art world. He is neither afraid to switch themes nor mediums. This is evident from the breadth of topics addressed by him. These have ranged from miniature painting like stylized portraits from 2003 to 2012 to depicting the totally barren mounds of Harappa – depicting clouds and dust storms especially since 2013. The variation in mediums is equally telling. This includes large size Mylar architectural sheets for his latest series of works on mounds, human hair used for installations, red baked clay to cast hundreds of hearts for the first Lahore Biennale and dozens of sparrows for the second edition of the Lahore Biennale that were deliberately made in clay to be washed away by rain.

Kazim’s personality is a character straight from a fiction book - a delicate, thin, and short figure with a soft-spoken Punjabi accent. He is mostly accompanied by a pet African Parrot sitting on his shoulder, who keeps grumbling in his ears about the intruding visitors to the studio. Kazim appears like a court painter of the Mughal era. The finesse and sensitivity of his personality is seen across his oeuvre. The 2018 Lahore Biennale piece comprising hundreds of red baked clay hearts was displayed in Lahore’s Lawrence Gardens. Kazim’s clay hearts were a requiem to the innumerable overt and covert courtships occurring in Lahore’s numerous parks and to the hearts carved on trees or drawn on benches by lovebirds. Kazim’s framing of hearts in the Lawrence Gardens was also based on the venue for Bano Qudsia’s epic novel Raja Gidh. The main characters of the novel, Seemi & Aftab, meet there and have a close association with the shrine of Shah Murad situated in the Lawrence Gardens.

Whether an artist should or should not be sensitive to a sense of history or place is a continuous debate. Pakistani modern painting has gone through different phases. In its early years it was dominated by trends denying the importance of resonating with local tradition and context. But in time many grudgingly connected with the Subcontinental civilization and identity. Appropriation of traditional arts across the world is now well documented such as the influence of North African tapestries on Monet or the sprinkling of African art in Picasso’s cubism – all making for a delightful study of cultural appropriation. Kazim belongs to the generation which, despite its modernist moorings, has embraced the depth and breadth of his Pakistani roots. He is an avid reader and his work is based on his understanding of history, literature and the Pakistani context.

Kazim spends a lot of time to conceive his projects. He does extensive research and goes around looking for the right subject matter and content. For his latest passion of exploring sites associated with the Gandhara and Indus Valley civilizations, he traveled to different parts of the country and read widely. He also read Urdu novel Bahao by Mustansar Hussain Tarar. Bahao is a story of the last days of a dying civilization next to the Ghagra Valley and is an underlying inspiration for Kazim’s latest series of work. He designed title of Tarar’s latest novel Mantaq-al-Tair Jadeed - a modern-day Conference of the Birds. Both the original Conference of the Birds and Tarar’s Mantaq-al-Tair Jadeed led to Kazim’s pe-and-ink bird series for the 2019 Karachi Biennale. This multi-panel work has a range of engaging birds marching behind their leader in search of self.

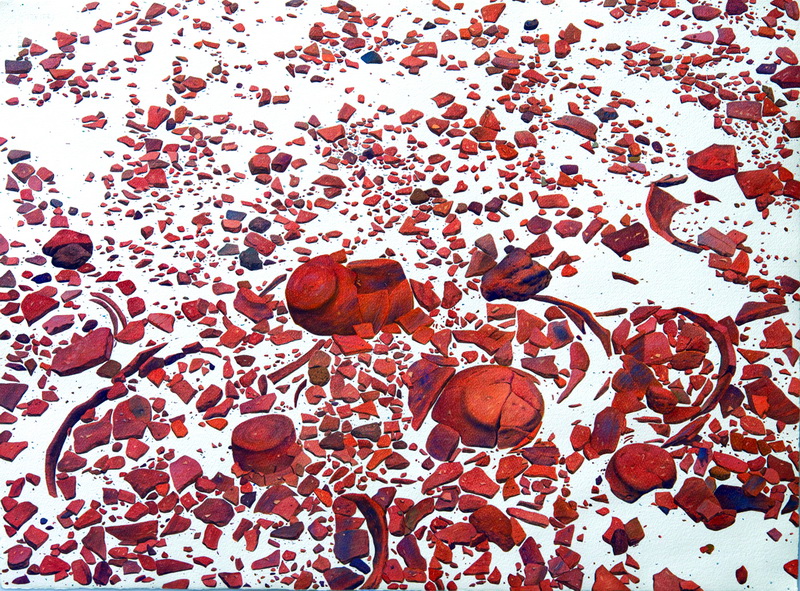

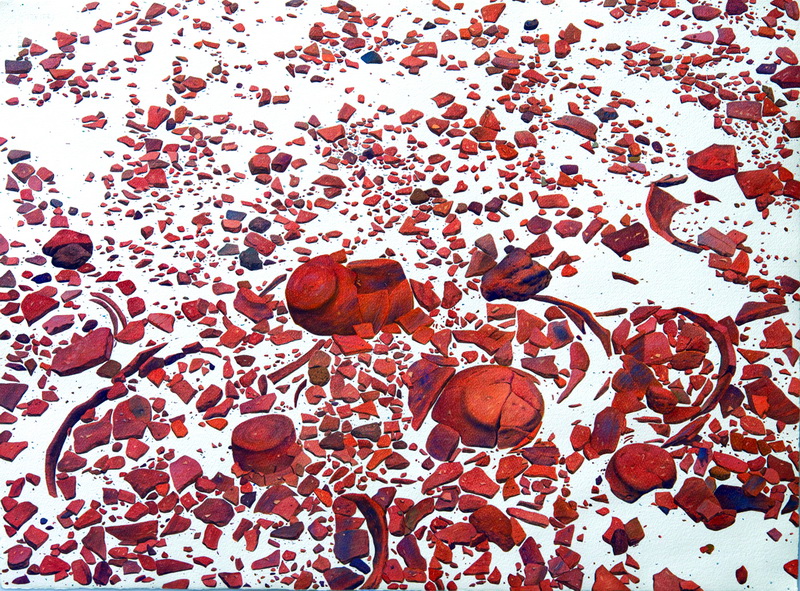

Pakistan has a rich tradition of landscape painting but illustrating monotone mounds or debris is not an easy task. It sounds like an otherwise bland topic for a visual artist to be attracted to. Visiting Harrapa or Moenjodara surroundings is a great experience but again a painting about it does not raise much curiosity. But here lies strength of a Kazim: that he presents a bland topic of study in a manner that the viewer is attracted towards it. Kazim has – with his detailed on-site study, research, and artistry – cast a spell when one looks at the Ruins series.

Kazim’s colour palette has been equally delightful but sublime as is seen in his portrait series. But for his latest works he has switched to black and white and to large scale panels – and an immersive technique. He uses pen and ink or watercolours to depict the wide stretches of grey or sepia mounds sprinkled with shards. He then casts rocks and shards and places them in front of his exhibited panels calling them “Fallen Objects.” These rocks look original but closer inspection reveals they are casted pieces in black colour. Kazim has been taken over by the romance of old civilizations and is now like a passionate archeologist. Kazim’s work for the Ninth Asia-Pacific Triennale featured his huge landscape of Harappa – probably the biggest he has done so far.

Kazim’s detail-oriented work and research on Gandhara civilizations has yielded him a residency at the Ashmolean Museum to study Oxford’s Gandhara collection. He recently spent some time there and will be visiting Oxford again. The residency will ultimately lead to a survey show in Summer of 2021.

In the second edition of the Lahore Biennale, Kazim did two projects. The first was with Aisha Khalid: a collateral project of about 2,500 clay sparrows in different poses and sizes placed around a brick kiln. The second was part of the Biennale display of Kazim’s figurative works at Punjab University. Both reflect the diversity in Kazim’s work that has been discussed earlier.

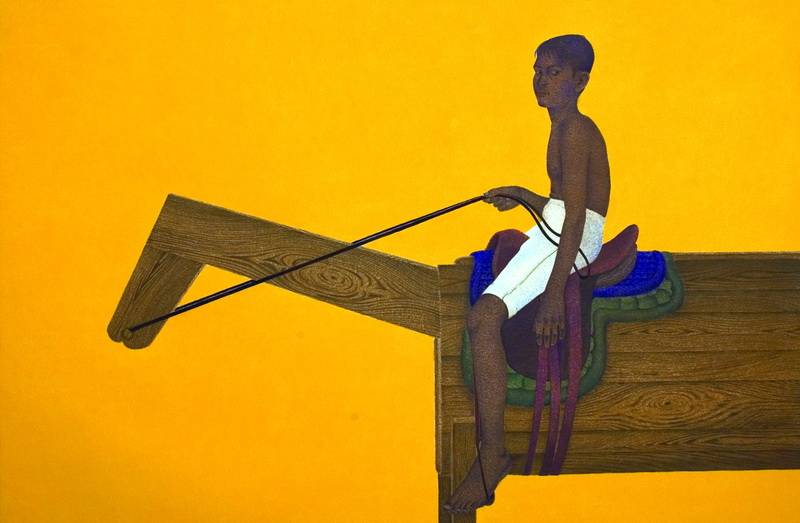

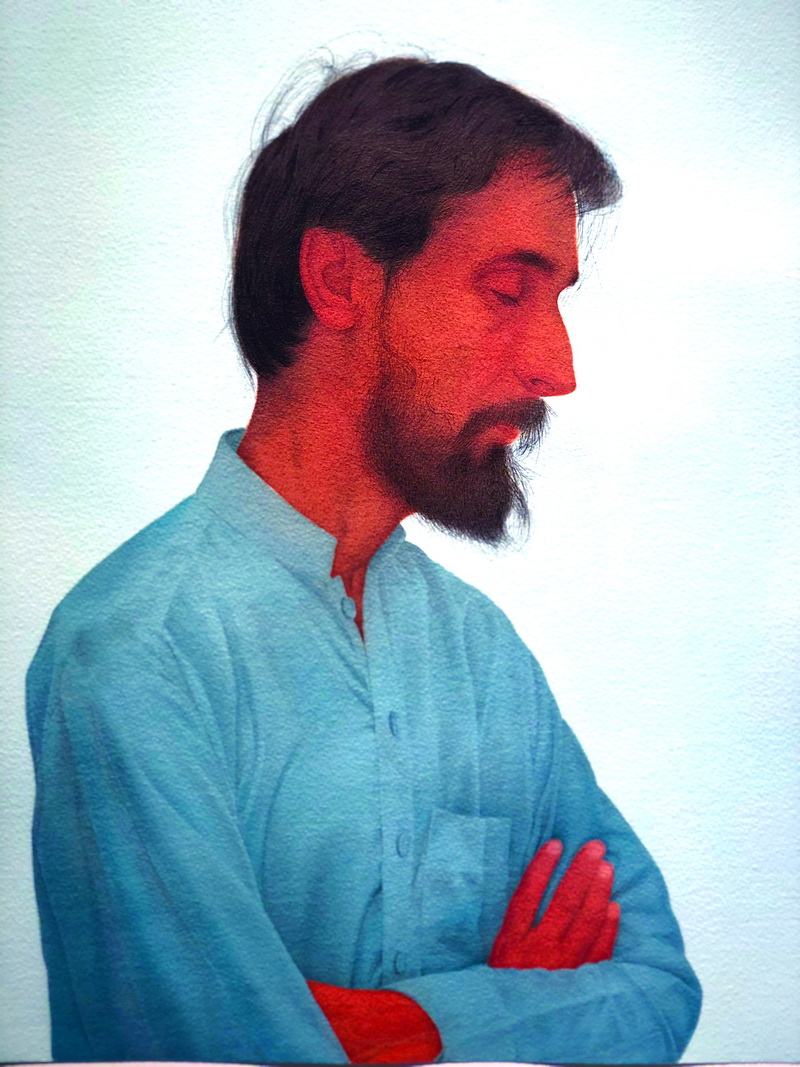

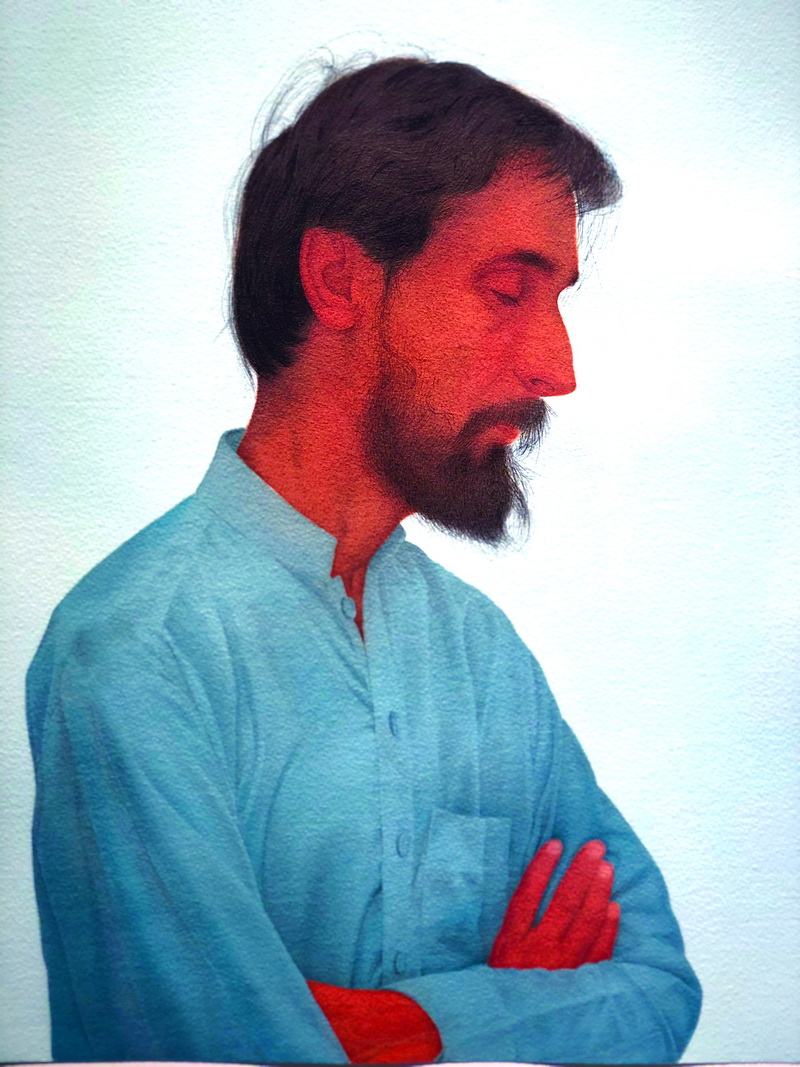

Kazim’s fascination for history is not new. His portrait series was influenced by the head of the Grand Priest of Moenjodaro from the Indus Civilization. He says, “Once I found that key, I was able to connect the posture and expressions of my different characters.” Kazim has studied portraits in a unique manner where a character’s gender and religious affiliations are pronounced through different symbols like a bald figure, tattoos on the neckline and even the placement of portraiture in the composition. Interestingly Kazim’s portraits do not look the viewer in the eyes like typical portraits but capture the subject in a certain posture. The viewer is struck by the posture and placement. Kazim’s colourful palette done in different washes of the Bengal School tradition on Wasli or paper gives the composition a design element e.g. ‘Peacock Boy’ or ‘Shah-Savar’ have a yellow background or ‘Man with Red Flower’ has a blue background. ‘Man with Firefly’ has a night-blue background. However, the subject is in monochrome - with brownish dark skins. Another of his series of self-portraits from 2010-11 has Kazim in different postures against a white background. The subjects in brown shades in Kazim’s work point towards the monochrome direction that he has taken.

Going from painting human beings to depicting vast desolate landscapes is quite a transition, though Kazim says that these landscapes are still about humans of the past, despite the absence of them in his works. For Kazim “a portrait is a work about one person and who they are or were. The landscapes are a collective portrait about a people.”

Kazim has a strange link with materials. Hair, clay or dust has a certain ephemeral character. Kazim says that for him arriving at the right material to express his theme has to be an organic link. Thus the use of black and white for depicting ruins, clouds or dust storms not only gives a textural quality to Kazim’s work but also an organic way of depiction. Kazim’s work appears simple and minimalist. Yet the process to arrive at the affect is taxing and tedious. Also, his multi-panel mounds with shards scattered along the panels seem to have a minimalist approach but drawing each and every shard and three to four panels of 3x7 feet are not only laborious tasks but a true labour of love.

No matter what subject or material Kazim turns to, his practice depicts a certain void - humanity’s isolation within the cosmos. His work is also full of a sense of timelessness, the landscape either in the beginning of time or the morning after the end of history. Kazim’s zest for exploration as an artist continues to grow and so does his stature as a visual artist.

The author can be reached smt2104@caa.columbia.edu

Kazim’s personality is a character straight from a fiction book - a delicate, thin, and short figure with a soft-spoken Punjabi accent. He is mostly accompanied by a pet African Parrot sitting on his shoulder, who keeps grumbling in his ears about the intruding visitors to the studio. Kazim appears like a court painter of the Mughal era. The finesse and sensitivity of his personality is seen across his oeuvre. The 2018 Lahore Biennale piece comprising hundreds of red baked clay hearts was displayed in Lahore’s Lawrence Gardens. Kazim’s clay hearts were a requiem to the innumerable overt and covert courtships occurring in Lahore’s numerous parks and to the hearts carved on trees or drawn on benches by lovebirds. Kazim’s framing of hearts in the Lawrence Gardens was also based on the venue for Bano Qudsia’s epic novel Raja Gidh. The main characters of the novel, Seemi & Aftab, meet there and have a close association with the shrine of Shah Murad situated in the Lawrence Gardens.

For Kazim “a portrait is a work about one person and who they are or were. The landscapes are a collective portrait about a people”

Whether an artist should or should not be sensitive to a sense of history or place is a continuous debate. Pakistani modern painting has gone through different phases. In its early years it was dominated by trends denying the importance of resonating with local tradition and context. But in time many grudgingly connected with the Subcontinental civilization and identity. Appropriation of traditional arts across the world is now well documented such as the influence of North African tapestries on Monet or the sprinkling of African art in Picasso’s cubism – all making for a delightful study of cultural appropriation. Kazim belongs to the generation which, despite its modernist moorings, has embraced the depth and breadth of his Pakistani roots. He is an avid reader and his work is based on his understanding of history, literature and the Pakistani context.

Kazim spends a lot of time to conceive his projects. He does extensive research and goes around looking for the right subject matter and content. For his latest passion of exploring sites associated with the Gandhara and Indus Valley civilizations, he traveled to different parts of the country and read widely. He also read Urdu novel Bahao by Mustansar Hussain Tarar. Bahao is a story of the last days of a dying civilization next to the Ghagra Valley and is an underlying inspiration for Kazim’s latest series of work. He designed title of Tarar’s latest novel Mantaq-al-Tair Jadeed - a modern-day Conference of the Birds. Both the original Conference of the Birds and Tarar’s Mantaq-al-Tair Jadeed led to Kazim’s pe-and-ink bird series for the 2019 Karachi Biennale. This multi-panel work has a range of engaging birds marching behind their leader in search of self.

Pakistan has a rich tradition of landscape painting but illustrating monotone mounds or debris is not an easy task. It sounds like an otherwise bland topic for a visual artist to be attracted to. Visiting Harrapa or Moenjodara surroundings is a great experience but again a painting about it does not raise much curiosity. But here lies strength of a Kazim: that he presents a bland topic of study in a manner that the viewer is attracted towards it. Kazim has – with his detailed on-site study, research, and artistry – cast a spell when one looks at the Ruins series.

Kazim’s colour palette has been equally delightful but sublime as is seen in his portrait series. But for his latest works he has switched to black and white and to large scale panels – and an immersive technique. He uses pen and ink or watercolours to depict the wide stretches of grey or sepia mounds sprinkled with shards. He then casts rocks and shards and places them in front of his exhibited panels calling them “Fallen Objects.” These rocks look original but closer inspection reveals they are casted pieces in black colour. Kazim has been taken over by the romance of old civilizations and is now like a passionate archeologist. Kazim’s work for the Ninth Asia-Pacific Triennale featured his huge landscape of Harappa – probably the biggest he has done so far.

No matter what subject or material Kazim turns to, his practice depicts a certain void - humanity’s isolation within the cosmos

Kazim’s detail-oriented work and research on Gandhara civilizations has yielded him a residency at the Ashmolean Museum to study Oxford’s Gandhara collection. He recently spent some time there and will be visiting Oxford again. The residency will ultimately lead to a survey show in Summer of 2021.

In the second edition of the Lahore Biennale, Kazim did two projects. The first was with Aisha Khalid: a collateral project of about 2,500 clay sparrows in different poses and sizes placed around a brick kiln. The second was part of the Biennale display of Kazim’s figurative works at Punjab University. Both reflect the diversity in Kazim’s work that has been discussed earlier.

Kazim’s fascination for history is not new. His portrait series was influenced by the head of the Grand Priest of Moenjodaro from the Indus Civilization. He says, “Once I found that key, I was able to connect the posture and expressions of my different characters.” Kazim has studied portraits in a unique manner where a character’s gender and religious affiliations are pronounced through different symbols like a bald figure, tattoos on the neckline and even the placement of portraiture in the composition. Interestingly Kazim’s portraits do not look the viewer in the eyes like typical portraits but capture the subject in a certain posture. The viewer is struck by the posture and placement. Kazim’s colourful palette done in different washes of the Bengal School tradition on Wasli or paper gives the composition a design element e.g. ‘Peacock Boy’ or ‘Shah-Savar’ have a yellow background or ‘Man with Red Flower’ has a blue background. ‘Man with Firefly’ has a night-blue background. However, the subject is in monochrome - with brownish dark skins. Another of his series of self-portraits from 2010-11 has Kazim in different postures against a white background. The subjects in brown shades in Kazim’s work point towards the monochrome direction that he has taken.

Going from painting human beings to depicting vast desolate landscapes is quite a transition, though Kazim says that these landscapes are still about humans of the past, despite the absence of them in his works. For Kazim “a portrait is a work about one person and who they are or were. The landscapes are a collective portrait about a people.”

Kazim has a strange link with materials. Hair, clay or dust has a certain ephemeral character. Kazim says that for him arriving at the right material to express his theme has to be an organic link. Thus the use of black and white for depicting ruins, clouds or dust storms not only gives a textural quality to Kazim’s work but also an organic way of depiction. Kazim’s work appears simple and minimalist. Yet the process to arrive at the affect is taxing and tedious. Also, his multi-panel mounds with shards scattered along the panels seem to have a minimalist approach but drawing each and every shard and three to four panels of 3x7 feet are not only laborious tasks but a true labour of love.

No matter what subject or material Kazim turns to, his practice depicts a certain void - humanity’s isolation within the cosmos. His work is also full of a sense of timelessness, the landscape either in the beginning of time or the morning after the end of history. Kazim’s zest for exploration as an artist continues to grow and so does his stature as a visual artist.

The author can be reached smt2104@caa.columbia.edu