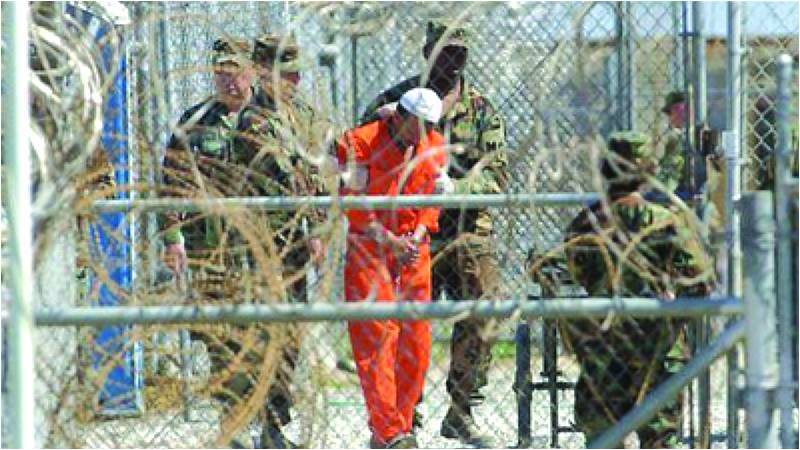

The detention facility in Parwan, otherwise known as the Bagram prison, is no longer operational. But the scars it has left on the minds and bodies of those imprisoned are unlikely to fade for a long time. In 2014, 43 Pakistanis returned to their homeland after spending several years in extrajudicial detainment. Torture remained rampant while the world stuffed quality cotton wool in its ears.

In the words of Hannah Arendt, evil is perhaps just banal to some.

Last year I spent listening to these stories up close and worked with lawyers and human rights champions who fought for repatriation of these destitute men day in and day out. Their battle wasn’t an easy one.

Naysayers termed the war against terror in Afghanistan ‘a non-international armed conflict,’ depriving the detainees in custody of their liberties. No international humanitarian law (IHL) safeguarded their basic rights. Even the notorious Geneva Convention failed them, providing little ground to challenge the legality of their detention. In the case of NIAC, neither does the Geneva Convention deal with reasons for detainment, nor does it establish procedures to challenge the legality of the act.

A group of overly clever personnel sitting in the Pentagon figured out ways to circumvent essentially every legal barrier and military tradition that stood in the way of unfettered display of power. They stripped vulnerable men off their habeas corpus rights, propelling them into a legal black hole.

There mustn’t be any two opinions that the international law needs to catch up. What brought these men relief, however, was the moral and legal liability of Pakistan. While the world made peace with the possibility of these disadvantaged men never returning home – despite being innocent in most cases – the Pakistani legal system reigned victorious.

Article 4 of the Constitution of Pakistan places a duty on the government to protect the rights of Pakistani citizens to be dealt with in accordance with the law, ‘wherever they may be.’ From 2010 to 2014, the Lahore High Court held hearings on the matter nearly every week until the Pakistani government acted. After almost four years of painstaking litigation and public awareness campaigns, 43 Pakistanis were finally repatriated – released without charge, but with years shaved off their lives.

Without the strong constitutional framework of this land, the repatriation of these men would have remained a dream. But the fight does not end here. Five years after this win, we must ask our collective conscience if the needle is moving in the right direction.

Today, if we fight the same case, will the constitution of Pakistan win again? Probably not.

The order of chaos, once an exception created by USA, the most powerful nation in the world, is now becoming an acceptable norm. Our own government’s moral authority is compromised today – stubbornness weighs heavier than fundamental rights.

Ever the playground for proxy wars, Pakistan is now officially seeing the erosion of its domestic legal order. From military courts and incommunicado detentions to internment camps and enforced disappearances, the country is deep into the abyss of embracing the same practices it stood against. It is now busy in disenfranchising the already disenfranchised. The recent detention of peaceful protestors is another demonstration of the same.

Domestic constitutional framework must be strengthened. A repetition of anything even remotely close to the Bagram ordeal, whether inside or outside, would be nothing short of a grave embarrassment. A uniform consular protection policy must also be implemented to safeguard rights of our citizens facing detention abroad. A well-established legal system within must look out for those who are left helpless by the international law outside.

The epidemic of systemic abuse that plagues us today has proven to be profoundly counterproductive – let us make sure it does not become a part of our permanent vocabulary.

The writer is a communications and policy professional working in the field of development and human rights

In the words of Hannah Arendt, evil is perhaps just banal to some.

Last year I spent listening to these stories up close and worked with lawyers and human rights champions who fought for repatriation of these destitute men day in and day out. Their battle wasn’t an easy one.

Naysayers termed the war against terror in Afghanistan ‘a non-international armed conflict,’ depriving the detainees in custody of their liberties. No international humanitarian law (IHL) safeguarded their basic rights. Even the notorious Geneva Convention failed them, providing little ground to challenge the legality of their detention. In the case of NIAC, neither does the Geneva Convention deal with reasons for detainment, nor does it establish procedures to challenge the legality of the act.

A group of overly clever personnel sitting in the Pentagon figured out ways to circumvent essentially every legal barrier and military tradition that stood in the way of unfettered display of power. They stripped vulnerable men off their habeas corpus rights, propelling them into a legal black hole.

There mustn’t be any two opinions that the international law needs to catch up. What brought these men relief, however, was the moral and legal liability of Pakistan. While the world made peace with the possibility of these disadvantaged men never returning home – despite being innocent in most cases – the Pakistani legal system reigned victorious.

Article 4 of the Constitution of Pakistan places a duty on the government to protect the rights of Pakistani citizens to be dealt with in accordance with the law, ‘wherever they may be.’ From 2010 to 2014, the Lahore High Court held hearings on the matter nearly every week until the Pakistani government acted. After almost four years of painstaking litigation and public awareness campaigns, 43 Pakistanis were finally repatriated – released without charge, but with years shaved off their lives.

Without the strong constitutional framework of this land, the repatriation of these men would have remained a dream. But the fight does not end here. Five years after this win, we must ask our collective conscience if the needle is moving in the right direction.

Today, if we fight the same case, will the constitution of Pakistan win again? Probably not.

The order of chaos, once an exception created by USA, the most powerful nation in the world, is now becoming an acceptable norm. Our own government’s moral authority is compromised today – stubbornness weighs heavier than fundamental rights.

Ever the playground for proxy wars, Pakistan is now officially seeing the erosion of its domestic legal order. From military courts and incommunicado detentions to internment camps and enforced disappearances, the country is deep into the abyss of embracing the same practices it stood against. It is now busy in disenfranchising the already disenfranchised. The recent detention of peaceful protestors is another demonstration of the same.

Domestic constitutional framework must be strengthened. A repetition of anything even remotely close to the Bagram ordeal, whether inside or outside, would be nothing short of a grave embarrassment. A uniform consular protection policy must also be implemented to safeguard rights of our citizens facing detention abroad. A well-established legal system within must look out for those who are left helpless by the international law outside.

The epidemic of systemic abuse that plagues us today has proven to be profoundly counterproductive – let us make sure it does not become a part of our permanent vocabulary.

The writer is a communications and policy professional working in the field of development and human rights