The mathematical roundness of a new decade is a momentous thing. It takes the refreshing energy of a regular New Year’s Eve and boosts it upwards – high enough to let you survey your last and next decade. Like in life, the (two thousand) teens were awkward and full of pimples. Despite avoiding insipid Facebook posts about self reflection, I have also been sucked into the melodrama of using the new decade to judge myself. All week I’ve been shuffling in trailing shawls, staring out of windows, holding steaming mugs of coffee while asking the big questions: Am I where I want to be? Am I who I wanted to be? Have I been following a plan or is life just us trying to duck out of the way of speeding objects and hoping you look good in pictures when you do? Is liposuction worth it?

A decade ago I was fresh-faced and newly returned to Pakistan. There was no electricity, no gas and the threat of terrorism had just begun to transform the urban landscape of Pakistan irrevocably. I came back deliberately, I told myself. In the way that a child runs into the night screaming to get over his fear of monsters, I came back to Pakistan to defeat the nagging idea that I couldn’t make a life here.

I was still getting over jet lag when a family friend suggested that I try teaching somewhere as a way to broaden my experience of both students and institutions. She taught second-year undergraduates at a government university and offered to let me accompany her to her class the next week as a guest-lecturer-cum-stalker. My short stint as a graduate T.A had long ago confirmed I lacked the patience necessary to treat noisy students kindly. But she insisted, and the next week I waited with her in a cold classroom as twenty coeds shuffled inside to hear her lecture about art history.

Eventually I was asked to speak to the group. Having so recently graduated myself, I told them I didn’t know much more than they did, and so we had a freewheeling talk about some images from Pakistani art history that I thought were cool. I had been warned to choose my images carefully and I had taken the advice seriously, sticking to landscapes and abstactions. But one of the images had a nude figure leaning over a patch of grass, and at the end of the slideshow, one student raised his hand. He was dressed, I still remember, in blue jeans and black hoodie with the word “Supreme” written across the chest.

“Thats un-Islamic” he said simply.

“What is?”

“The picture of the woman. Its ‘behooda’ [indecent].”

The air went out of the room. Before I could reply, one of the other students put her hand up and asked me whether I had ever had an office job or had always been self employed. Grateful for the non-sequitur, I told them about the time I was working at a human rights organization, and then sort of ever off on my own tangent about how even the most non-traditional desk job is still a desk job – when the debate was take over by another voice at the back of the room.

This one said that he didn’t trust the nature of human rights NGOs, that they were covers for foreign spy agencies in Pakistan. Thankfully the bell rang and class ended.

“It’s all fine,” my friend said as we walked back to her car, “as long as you don’t ruffle too many feathers. You never know who you’ll have in your class.” It reminded me of how my O-levels biology teacher had to teach us about evolution in code, in case the Islamist department head overheard us next door.

That was the last time I considered teaching in Pakistan because I realized early on that no matter where you are or what you teach, you are always at risk. In a country as regressively confused as ours, even the mildest statement of fact can be twisted through the prism of Bronze Age morality into a weapon sharp enough to kill you. It is a lesson that still holds true.

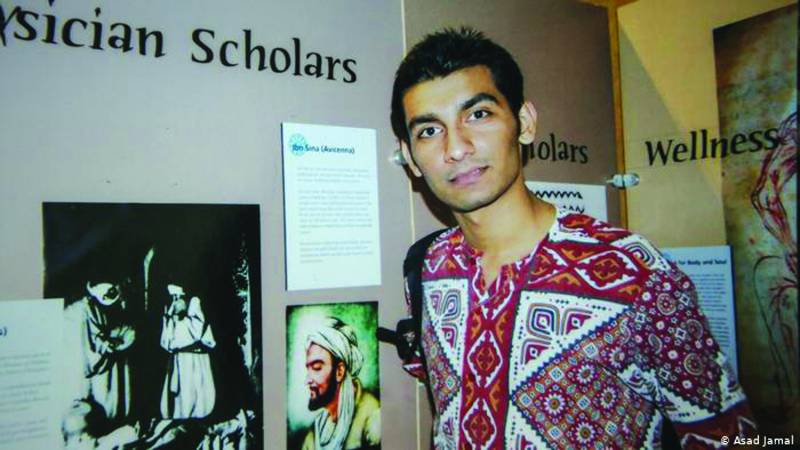

Junaid Hafeez also returned to Pakistan after graduate school in the US nearly a decade ago. He had studied American literature and photography there before coming back to teach in Multan, where he was arrested on blasphemy charges and accused by students over a Facebook post. His first lawyer was killed for defending him. He was subsequently held in solitary confinement for the next several years because other prisoners were attacking him. He has now been sentenced to death.

The endemic problems that allow for this abuse of justice are the same ones that made people defend Governor Taseer’s murderer and Malala’s shooters. They are not going to be assuaged by people like me teaching art history. To live here as a secular humanist is to know that you are outnumbered my a mob mentality that believes that you – not what you believe, but your very person – is wrong and should not exist. The exhausting daily battle against erasure is one of reasons I chose to make a life outside of Pakistan. It is also, paradoxically, why I keep coming back.

The last decade showed me that no one is ever really safe here. It is my New Year’s wish that the next one prove me wrong.

Write to thekantawala@gmail.com

A decade ago I was fresh-faced and newly returned to Pakistan. There was no electricity, no gas and the threat of terrorism had just begun to transform the urban landscape of Pakistan irrevocably. I came back deliberately, I told myself. In the way that a child runs into the night screaming to get over his fear of monsters, I came back to Pakistan to defeat the nagging idea that I couldn’t make a life here.

I was still getting over jet lag when a family friend suggested that I try teaching somewhere as a way to broaden my experience of both students and institutions. She taught second-year undergraduates at a government university and offered to let me accompany her to her class the next week as a guest-lecturer-cum-stalker. My short stint as a graduate T.A had long ago confirmed I lacked the patience necessary to treat noisy students kindly. But she insisted, and the next week I waited with her in a cold classroom as twenty coeds shuffled inside to hear her lecture about art history.

To live here as a secular humanist is to know that you are outnumbered my a mob mentality that believes that you – not what you believe, but your very person – is wrong and should not exist

Eventually I was asked to speak to the group. Having so recently graduated myself, I told them I didn’t know much more than they did, and so we had a freewheeling talk about some images from Pakistani art history that I thought were cool. I had been warned to choose my images carefully and I had taken the advice seriously, sticking to landscapes and abstactions. But one of the images had a nude figure leaning over a patch of grass, and at the end of the slideshow, one student raised his hand. He was dressed, I still remember, in blue jeans and black hoodie with the word “Supreme” written across the chest.

“Thats un-Islamic” he said simply.

“What is?”

“The picture of the woman. Its ‘behooda’ [indecent].”

The air went out of the room. Before I could reply, one of the other students put her hand up and asked me whether I had ever had an office job or had always been self employed. Grateful for the non-sequitur, I told them about the time I was working at a human rights organization, and then sort of ever off on my own tangent about how even the most non-traditional desk job is still a desk job – when the debate was take over by another voice at the back of the room.

This one said that he didn’t trust the nature of human rights NGOs, that they were covers for foreign spy agencies in Pakistan. Thankfully the bell rang and class ended.

“It’s all fine,” my friend said as we walked back to her car, “as long as you don’t ruffle too many feathers. You never know who you’ll have in your class.” It reminded me of how my O-levels biology teacher had to teach us about evolution in code, in case the Islamist department head overheard us next door.

That was the last time I considered teaching in Pakistan because I realized early on that no matter where you are or what you teach, you are always at risk. In a country as regressively confused as ours, even the mildest statement of fact can be twisted through the prism of Bronze Age morality into a weapon sharp enough to kill you. It is a lesson that still holds true.

Junaid Hafeez also returned to Pakistan after graduate school in the US nearly a decade ago. He had studied American literature and photography there before coming back to teach in Multan, where he was arrested on blasphemy charges and accused by students over a Facebook post. His first lawyer was killed for defending him. He was subsequently held in solitary confinement for the next several years because other prisoners were attacking him. He has now been sentenced to death.

The endemic problems that allow for this abuse of justice are the same ones that made people defend Governor Taseer’s murderer and Malala’s shooters. They are not going to be assuaged by people like me teaching art history. To live here as a secular humanist is to know that you are outnumbered my a mob mentality that believes that you – not what you believe, but your very person – is wrong and should not exist. The exhausting daily battle against erasure is one of reasons I chose to make a life outside of Pakistan. It is also, paradoxically, why I keep coming back.

The last decade showed me that no one is ever really safe here. It is my New Year’s wish that the next one prove me wrong.

Write to thekantawala@gmail.com