I grew up in Rawalpindi, a garrison town that was once merely a village by the name of Rawal. The time was the early 80’s and afterwards. I, and people who experienced that era, remember vividly a comparatively clean city which had its own heart and soul. The nearby Margalla hills were more than visible from every side, and its lush green sight was a marvel to behold. Its air was clean, even its tap water drinkable with plenty of supply, its seasons enjoyable and festive occasions of much joy. In an era when the likes of Imran, Miandad and Akram were household names, there were enough open spaces in the city where young people could fine tune their skills not just in cricket, but also in other sports like hockey and soccer. Reaching one end of the city from another was hardly a problem, either by public transport or by car. And not to mention that accessing quality fresh fruit, vegetables and dairy products was almost in everybody’s reach.

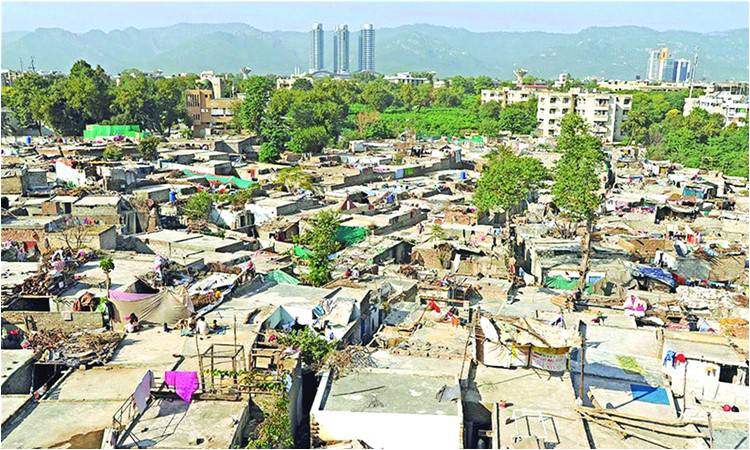

That Rawalpindi is now a distant memory. It now presents a picture of a barricaded city that is overcrowded, polluted and congested. Water availability throughout the year is a severe problem. Forget clean drinking water, taps have run dry for many years now. People have to travel to various places in search of drinking water. The city is dotted with security check posts all around, which makes vehicular movement a terrible ordeal. Many of is roads have been cordoned off and shut down by security organizations. Open areas and grounds have vanished, either occupied by different public or private groups or replaced with ugly looking cemented structures. Its roads are choked and its air polluted.

This story is not unique to Rawalpindi. Other cities like Lahore and Karachi have suffered the same fate. I used to travel to Lahore every year, especially on the occasion of Basant. On that particular day, combined with its culture, Lahore felt like the heart of the whole world and not just Pakistan. I loved every bit of it. Last year, it gained the unwanted distinction of the most polluted city in the world, with basant now a thing of memories. The lesser said about Karachi the better, which now presents the picture of giant waste dump rather than the city of lights.

I now live in Islamabad since 2012, Rawalpindi’s ‘sister’ city, in one of the relatively newer sectors. There is no running water, the roads make one feel like one is travelling on the lunar surface, the putrid smell of open sewers are an absolute nuisance, and heaps of exposed garbage lie everywhere in the four sections of the sector. To find fresh fruit and vegetable, residents usually head to the ‘sabzi mandi’ because the prices in most sectors become unbearable for even the middle class. Its ‘sasta bazars’, where subsidised and imported second-hand goods abound, are thronged by the all and sundry, from rich to the poorest, an indicator of how dear necessities have become. This is a far cry from the city where people came to find solace and quietness, and whose captivating beauty set it apart.

The story is not unique to cities only since villages have suffered the same fate. My ancestral village is in Malakand was once the most scenic places in Pakistan where vast, open agricultural lands were fed by a canal built by the English. The cool, crystal clear waters of river Swat provided much needed relief in summers, buffeted by pure, clean air and hundreds of dense, huge sheesham trees that neatly lined the canals (planted by the English in early 1900s). Now, the canal and the river are polluted beyond imagination, as everything from sewerage to waste products (chemicals, foods, plastic) are dumped into it and those beautiful sheesham trees have been chopped off long ago by timber mafia in connivance with local officials. Its air is now of a lesser quality as vehicular traffic and the use of pesticide spray has increased manifold, making its once pure water less safe to drink and use.

What is happening in Pakistan, especially its cities, is the effect of ‘unfriendly densities’ coupled with absence of any meaningful governance. Historically, the growth in per capita density has resulted in positive economic spill overs in the form of innovation, increased exchange and increased specialization, ultimately feeding into economic expansion. But economists are now questioning whether density beyond a point becomes a drag upon economic growth? They posit that as places become dense beyond a certain limit, positive spill overs of density turn the other way around. A recent study by economist Jordan Rappaport seems to confirm this theory. He collected data on population and job growth for more than 350 metropolitan areas, and found that heavy density generated diseconomies like traffic congestion or expensive housing costs, which limited growth.

Same diseconomies have engulfed Pakistan’s larger cities and its geography in general. Just look at the everyday traffic gridlocks in cities, and how much it costs in terms of time, added expenses on fuel and pollution. There are other serious repercussions of such unfriendly densities. Take also, for example, the case of noise pollution in Pakistani cities. In west, noise pollution is now being treated as a health emergency by many since there is incontrovertible proof that noise pollution leads to hearing loss, psychiatric problems, cardiovascular diseases and delayed language development. In Pakistan’s major cities, you’d be lucky to find empty roads even after mid-night, or spared the discomfort of un-civilized neighbors honking horns even at midnight. And things get worse when it comes to marriage festivities that run through the whole night. In short, a comforting sleep is out of reach of a substantial number of Pakistanis now.

The physical development of our children is at a distinct disadvantage because there are no grounds and open spaces to speak of. In the sector where I live, grounds exist on maps only, and whatever little space there is, it is contested by groups who don’t let others use the space. Where children do find a bit of space to play, usually on the streets, they are strictly told to limit the range of shots they can play, limiting the development of their locomotive skills and physical abilities. Walking spaces are absent, especially for women who find it difficult to walk and exercise freely away from the prying eyes of male folks. Just imagine these problems as a whole, to make an estimate of how much damage is being done to our people.

In conclusion, the quality of life in Pakistan has suffered a gradual decline, especially in major cities. The growth in GDP or per capita income should not blind us to this downward trajectory. This is one reason that many economists view GDP as a lousy indicator of the quality of life. More on this aspect in a future column. For the moment, we should worry about the overall challenging environment that engulfs us in Pakistan. Does anybody know of any ‘PC-I’ or any manifesto of political party that addresses these challenges? I have yet to come across one!

The writer is an economist

That Rawalpindi is now a distant memory. It now presents a picture of a barricaded city that is overcrowded, polluted and congested. Water availability throughout the year is a severe problem. Forget clean drinking water, taps have run dry for many years now. People have to travel to various places in search of drinking water. The city is dotted with security check posts all around, which makes vehicular movement a terrible ordeal. Many of is roads have been cordoned off and shut down by security organizations. Open areas and grounds have vanished, either occupied by different public or private groups or replaced with ugly looking cemented structures. Its roads are choked and its air polluted.

This story is not unique to Rawalpindi. Other cities like Lahore and Karachi have suffered the same fate. I used to travel to Lahore every year, especially on the occasion of Basant. On that particular day, combined with its culture, Lahore felt like the heart of the whole world and not just Pakistan. I loved every bit of it. Last year, it gained the unwanted distinction of the most polluted city in the world, with basant now a thing of memories. The lesser said about Karachi the better, which now presents the picture of giant waste dump rather than the city of lights.

I now live in Islamabad since 2012, Rawalpindi’s ‘sister’ city, in one of the relatively newer sectors. There is no running water, the roads make one feel like one is travelling on the lunar surface, the putrid smell of open sewers are an absolute nuisance, and heaps of exposed garbage lie everywhere in the four sections of the sector. To find fresh fruit and vegetable, residents usually head to the ‘sabzi mandi’ because the prices in most sectors become unbearable for even the middle class. Its ‘sasta bazars’, where subsidised and imported second-hand goods abound, are thronged by the all and sundry, from rich to the poorest, an indicator of how dear necessities have become. This is a far cry from the city where people came to find solace and quietness, and whose captivating beauty set it apart.

The story is not unique to cities only since villages have suffered the same fate. My ancestral village is in Malakand was once the most scenic places in Pakistan where vast, open agricultural lands were fed by a canal built by the English. The cool, crystal clear waters of river Swat provided much needed relief in summers, buffeted by pure, clean air and hundreds of dense, huge sheesham trees that neatly lined the canals (planted by the English in early 1900s). Now, the canal and the river are polluted beyond imagination, as everything from sewerage to waste products (chemicals, foods, plastic) are dumped into it and those beautiful sheesham trees have been chopped off long ago by timber mafia in connivance with local officials. Its air is now of a lesser quality as vehicular traffic and the use of pesticide spray has increased manifold, making its once pure water less safe to drink and use.

What is happening in Pakistan, especially its cities, is the effect of ‘unfriendly densities’ coupled with absence of any meaningful governance. Historically, the growth in per capita density has resulted in positive economic spill overs in the form of innovation, increased exchange and increased specialization, ultimately feeding into economic expansion. But economists are now questioning whether density beyond a point becomes a drag upon economic growth? They posit that as places become dense beyond a certain limit, positive spill overs of density turn the other way around. A recent study by economist Jordan Rappaport seems to confirm this theory. He collected data on population and job growth for more than 350 metropolitan areas, and found that heavy density generated diseconomies like traffic congestion or expensive housing costs, which limited growth.

Same diseconomies have engulfed Pakistan’s larger cities and its geography in general. Just look at the everyday traffic gridlocks in cities, and how much it costs in terms of time, added expenses on fuel and pollution. There are other serious repercussions of such unfriendly densities. Take also, for example, the case of noise pollution in Pakistani cities. In west, noise pollution is now being treated as a health emergency by many since there is incontrovertible proof that noise pollution leads to hearing loss, psychiatric problems, cardiovascular diseases and delayed language development. In Pakistan’s major cities, you’d be lucky to find empty roads even after mid-night, or spared the discomfort of un-civilized neighbors honking horns even at midnight. And things get worse when it comes to marriage festivities that run through the whole night. In short, a comforting sleep is out of reach of a substantial number of Pakistanis now.

The physical development of our children is at a distinct disadvantage because there are no grounds and open spaces to speak of. In the sector where I live, grounds exist on maps only, and whatever little space there is, it is contested by groups who don’t let others use the space. Where children do find a bit of space to play, usually on the streets, they are strictly told to limit the range of shots they can play, limiting the development of their locomotive skills and physical abilities. Walking spaces are absent, especially for women who find it difficult to walk and exercise freely away from the prying eyes of male folks. Just imagine these problems as a whole, to make an estimate of how much damage is being done to our people.

In conclusion, the quality of life in Pakistan has suffered a gradual decline, especially in major cities. The growth in GDP or per capita income should not blind us to this downward trajectory. This is one reason that many economists view GDP as a lousy indicator of the quality of life. More on this aspect in a future column. For the moment, we should worry about the overall challenging environment that engulfs us in Pakistan. Does anybody know of any ‘PC-I’ or any manifesto of political party that addresses these challenges? I have yet to come across one!

The writer is an economist