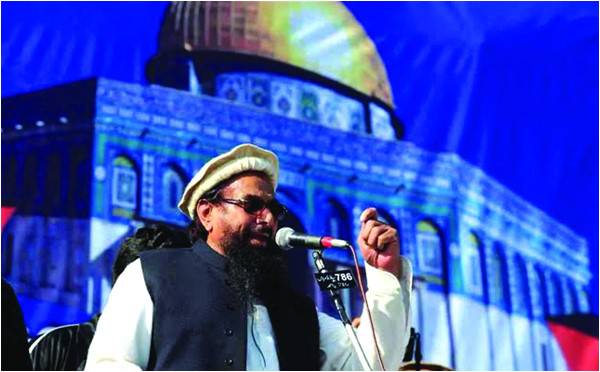

It appears that a course correction is in the works on the issue of militant organisations and cross-border militancy, or at least it seems so. The main centre of Jamaatud Dawah (JuD) in Muridke has been taken over by the Punjab government and Hafiz Saeed’s activities have been restricted. Hundreds of madrassas and seminaries run by banned outfits have been sealed by provincial governments. Hopefully the perils of a selective approach towards militant groups have dawned more clearly, though it is not the first time that a crackdown has been launched.

A similar crackdown was first announced by General Musharraf in January 2002, within a month of the attack on the Indian parliament on December 13, 2001. Soon it transpired that the crackdown was not real and the ban was re-imposed in November 2003. A decade later, in March 2013, the parliament passed a law banning the resurrection of proscribed outfits in any form. Two years later, it was reiterated in the National Action Plan. However, the policy of “running with the hare and hunting with the hound” - as Benazir Bhutto had called it - continued.

It is too early to say whether the current clampdown is cosmetic or inspired by a genuine realisation of the need for course correction. The national and international environment at the end of the second decade of the 21st century, however, is different from the one at its beginning. It raises one’s hopes.

During the last two decades, the perception that Pakistan-based militants backed by elements within state institutions have exported militancy across borders strengthened both nationally and internationally. Attacks have been carried out, not only inside Kashmir, but also in mainland India, as the November 2008 attack in Mumbai. Debates in the parliament also exposed structural weaknesses in the promised curbing of militants.

The reaction to Pulwama has dangerously lowered the threshold of mutual provocations, and by corollary the nuclear threshold, between the two countries.

Mumbai, as an attack on mainland India by Pakistan-based non-state actors, was far more serious but it was not met with strong military retaliation by India. The Pathankot incident on the New Year eve in 2016 drew a warning from India of surgical strikes. After the Uri incident towards the end of that year, India claimed to have actually carried out a surgical strike in Pakistani part of Kashmir. The international border, however, was not crossed. Pakistan rejected the Indian claim and warned that any such misadventure would draw an immediate response.

Pulwama lowered the provocation threshold further. By striking at Balakot across the international border, India seemingly carried out its threat to strike at a target and at a time of its choice. Pakistan, too, promptly carried out its threat to strike back. Apart from dropping some bombs in the Indian-administered Kashmir, it also shot down two Indian war planes in a dogfight.

Mercifully, each carried out its threat in a nuanced and calculated manner to avoid real damage and there was no further escalation. Next time, however, the luxury of nuanced and calculated responses may not be permitted by the dynamics of the situation and escalation may be inevitable.

One would like to hope that the changed ground realities would persuade both countries to do some strategic re-thinking. It is quite possible, though by no means certain, that the crackdown on militants in Pakistan is the result of some strategic re-thinking.

A real strategic re-thinking in course correction, however, should be holistic in approach and not limited to militant outfits only. It should also encompass the running of the statecraft itself.

Any course correction in Pakistan must also seek to address the distortions in the civil-military relationship. The need for the restoration of the writ of the de-jure government as against the de-facto part controlling the lever of state power has never been as great as it is today. A vehicle whose vital control is in the hands of an unaccountable backseat driver and not the one on the wheel is doomed to meet a serious accident. This perilous syndrome must come to an end, the mantra of ‘same page’ notwithstanding. Dawn Leaks in October 2016 was all about this peril.

A course correction also needs to be made by allowing space for freedom of discussion, dissent and association. The thoughtless crackdown recently on the NGOs and the unannounced censorship of media has shrunk the space for dissent and peaceful protests. Squeezing this space will only encourage violence and promote rumours and falsehood. It is unwise to dismiss peaceful protesting voices like that of Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM) as anti-state and stifling them by intimidation and coercion.

Insistence on a uniform media regulatory authority must also be abandoned. The proposal was first made during the last days of the previous PML-N government when it was beleaguered and besieged and unable to resist. That it is now also on the agenda of the PTI government suggests that the real backers of the proposal are the de-facto masters of the country.

Curtailing freedom of expression and the space for civil society organisations will prove counterproductive. It would be wise to reconsider the decision of taking away registration and oversight of NGOs from the Economic Affairs Division and placing them in the hands of Interior Ministry acting upon the advice of intelligence agencies. Wolfs must not be called upon to guard the sheep. Oversight of the NGO sector must be through parliamentary legislation and not under any executive order of law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

It is good to recognise that the activities of militant organisations are against national interests. It should also be recognised that dissent, peaceful demonstrations and monitoring of human rights violations are not against national interests. Those who speak for women’s economic and political right are not working against social values and those demanding justice for minority communities are not foreign agents.

Those who think otherwise should heed the words of former UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon: “If leaders do not listen to their people, they will hear from them — on the streets, the square, or, as we see far too often, on the battlefield. There is a better way. More participation. More democracy. More engagement and openness. That means maximum space for civil society.”

To Ban Ki Moon’s prescription one may also add: “No space for back seat driving.”

The writer is a former senator

A similar crackdown was first announced by General Musharraf in January 2002, within a month of the attack on the Indian parliament on December 13, 2001. Soon it transpired that the crackdown was not real and the ban was re-imposed in November 2003. A decade later, in March 2013, the parliament passed a law banning the resurrection of proscribed outfits in any form. Two years later, it was reiterated in the National Action Plan. However, the policy of “running with the hare and hunting with the hound” - as Benazir Bhutto had called it - continued.

It is too early to say whether the current clampdown is cosmetic or inspired by a genuine realisation of the need for course correction. The national and international environment at the end of the second decade of the 21st century, however, is different from the one at its beginning. It raises one’s hopes.

Wolfs must not be called upon to guard the sheep. Oversight of the NGO sector must be through parliamentary legislation and not under any executive order of law enforcement and intelligence agencies

During the last two decades, the perception that Pakistan-based militants backed by elements within state institutions have exported militancy across borders strengthened both nationally and internationally. Attacks have been carried out, not only inside Kashmir, but also in mainland India, as the November 2008 attack in Mumbai. Debates in the parliament also exposed structural weaknesses in the promised curbing of militants.

The reaction to Pulwama has dangerously lowered the threshold of mutual provocations, and by corollary the nuclear threshold, between the two countries.

Mumbai, as an attack on mainland India by Pakistan-based non-state actors, was far more serious but it was not met with strong military retaliation by India. The Pathankot incident on the New Year eve in 2016 drew a warning from India of surgical strikes. After the Uri incident towards the end of that year, India claimed to have actually carried out a surgical strike in Pakistani part of Kashmir. The international border, however, was not crossed. Pakistan rejected the Indian claim and warned that any such misadventure would draw an immediate response.

Pulwama lowered the provocation threshold further. By striking at Balakot across the international border, India seemingly carried out its threat to strike at a target and at a time of its choice. Pakistan, too, promptly carried out its threat to strike back. Apart from dropping some bombs in the Indian-administered Kashmir, it also shot down two Indian war planes in a dogfight.

Mercifully, each carried out its threat in a nuanced and calculated manner to avoid real damage and there was no further escalation. Next time, however, the luxury of nuanced and calculated responses may not be permitted by the dynamics of the situation and escalation may be inevitable.

One would like to hope that the changed ground realities would persuade both countries to do some strategic re-thinking. It is quite possible, though by no means certain, that the crackdown on militants in Pakistan is the result of some strategic re-thinking.

A real strategic re-thinking in course correction, however, should be holistic in approach and not limited to militant outfits only. It should also encompass the running of the statecraft itself.

Any course correction in Pakistan must also seek to address the distortions in the civil-military relationship. The need for the restoration of the writ of the de-jure government as against the de-facto part controlling the lever of state power has never been as great as it is today. A vehicle whose vital control is in the hands of an unaccountable backseat driver and not the one on the wheel is doomed to meet a serious accident. This perilous syndrome must come to an end, the mantra of ‘same page’ notwithstanding. Dawn Leaks in October 2016 was all about this peril.

A course correction also needs to be made by allowing space for freedom of discussion, dissent and association. The thoughtless crackdown recently on the NGOs and the unannounced censorship of media has shrunk the space for dissent and peaceful protests. Squeezing this space will only encourage violence and promote rumours and falsehood. It is unwise to dismiss peaceful protesting voices like that of Pashtun Tahaffuz Movement (PTM) as anti-state and stifling them by intimidation and coercion.

Insistence on a uniform media regulatory authority must also be abandoned. The proposal was first made during the last days of the previous PML-N government when it was beleaguered and besieged and unable to resist. That it is now also on the agenda of the PTI government suggests that the real backers of the proposal are the de-facto masters of the country.

Curtailing freedom of expression and the space for civil society organisations will prove counterproductive. It would be wise to reconsider the decision of taking away registration and oversight of NGOs from the Economic Affairs Division and placing them in the hands of Interior Ministry acting upon the advice of intelligence agencies. Wolfs must not be called upon to guard the sheep. Oversight of the NGO sector must be through parliamentary legislation and not under any executive order of law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

It is good to recognise that the activities of militant organisations are against national interests. It should also be recognised that dissent, peaceful demonstrations and monitoring of human rights violations are not against national interests. Those who speak for women’s economic and political right are not working against social values and those demanding justice for minority communities are not foreign agents.

Those who think otherwise should heed the words of former UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon: “If leaders do not listen to their people, they will hear from them — on the streets, the square, or, as we see far too often, on the battlefield. There is a better way. More participation. More democracy. More engagement and openness. That means maximum space for civil society.”

To Ban Ki Moon’s prescription one may also add: “No space for back seat driving.”

The writer is a former senator