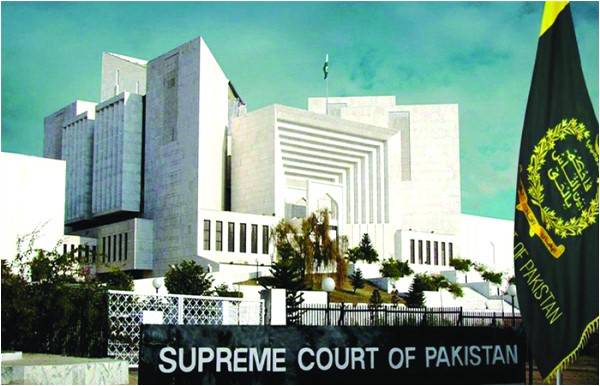

The detailed verdict of the Supreme Court in the Faizabad dharna case last week will be regarded as a milestone in the nation’s journey to correct its course, holding the mighty and powerful accountable and illumining the democratic path.

The verdict delivered by Justice Mushir Alam and Justice Qazi Faez Isa also opens enormous possibilities for the parliament and state institutions. Consider.

First, the government was told that the protesters of the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) dharna must be proceeded against under the Pakistan Penal Code, the Anti-Terrorism Act, 1997 or the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, 2016 and brought to justice.

Second, it asked the Election Commission of Pakistan to proceed against a political party (TLP) that does not comply with laws governing political parties.

Third, touching upon complaints of media bodies, it declared illegal the advice of self-censorship to suppress independent viewpoints and asked Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA) to take action in complaints against interference in broadcasts and delivery of publications in cantonment areas and Defence Housing Authorities. If such interference was done on the behest of others, then PEMRA should report it to the authorities concerned, the judgement said. Tactics such as directions to media organizations as to who should be hired or fired were also declared illegal.

Fourth, with regards to reining in state intelligence agencies and ensuring transparency and rule of law, the court ordered making legislation to clearly stipulate the respective mandates of the intelligence agencies.

Fifth, reminding the armed forces of constitutional restrictions on engaging in politicking, the court ordered the Defence Ministry and respective chiefs of the Army, Navy and Air Force to penalise the personnel found to have violated their oath. “We must not allow the honour and esteem due to those who lay down their lives for others to be undermined by the illegal actions of a few,” it presciently observed.

Sixth, copies of the judgment were sent for information and compliance to all quarters, namely the relevant federal secretaries, the three services chiefs, provincial chief secretaries, the election commission, PEMRA and the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) among others.

It is true that the observations made by the SC can be heard almost daily from civil society organizations in seminars and public discussions. But the difference lies in the authenticity and weight lent to such observations when they come from Supreme Court, and the clear cut directions given by the court on the steps to be taken. Failure on the part of the government and relevant bodies is sure to attract contempt provisions.

By making this declaration, the SC has opened doors for the parliament to enact appropriate legislation for determining the mandate of intelligence agencies. A great opportunity has been provided to the parliament and the state’s democratic institutions to end the era of contempt of the people so blatantly manifested in manipulated power transfer, distorted civil-military relations, backdoor re-engineering of political landscape and stifling dissent.

Sometime back, an aborted attempt was made in the Senate to bring ISI under the legislative framework. As a consequence of the SC order, the Upper House now has a unique opportunity to revive the aborted bid of the past. If the parliament fails to enact such legislation, it will have no one to blame except itself.

The directions to the Defence Ministry and the three services chiefs to penalise the personnel of the forces found to have violated their oath is a breath of fresh air. It will be naive to expect that those who violated their oath will be actually penalised anytime soon. The important thing is not to penalise them instantly. It is the opportunity to set in motion the process of accountability. The two-decades-old petition of Air Marshal Asghar Khan may still not have brought the perpetrators to justice, but it will be unfair to say that it has served no useful purpose. The ghost of late Asghar Khan continues to haunt wrongdoers and sends a warning signal to would-be perpetrators. That in itself is no small achievement.

The court’s orders to PEMRA to take action against cable operators who shut broadcasts and those who interfered with the distribution of publications in cantonment areas is also highly significant for the potential it holds. PEMRA is now under obligation to investigate the matter and its failure will give an opportunity to rights activists to agitate the matter inside and outside the courts. The possibilities indeed are exciting.

There is lot in the verdict for restoration of freedom of expression and dissent. The court observed that PEMRA had failed to protect legitimate rights of its licensed broadcasters. Broadcasts by Dawn and Geo were interrupted in DHAs and this interruption was duly acknowledged by PEMRA as it failed to take action and ‘sadly looked the other way.’ On two occasions, PEMRA was asked as to who was responsible. Its representatives professed ignorance, the court noted.

This is not only a stinging indictment of PEMRA, it also places in the hands of media organizations a powerful tool to regain their lost freedoms.

The ball is now in the court of political parties, the parliament, media organisations and civil society organisations. For far too long, political governments have bent over backwards to woo anti-democratic forces for elusive political stability. Opposition parties, on the other hand, have colluded with these anti-democracy forces to bring down the government. In between, the anti-democratic forces have jeered at politicians and made hay while the sun shone for them.

It will be wrong to see the verdict as a report by the Judicial Commission that makes some broad-based recommendations and may not have the same enforcement authority as that of a court order. There are specific orders in the Faizabad dharna case verdict that have to be complied with and failure to do so will entail consequences.

The SC verdict offers so much but only if the political class and civil society grasped its significance, mended their ways and begin to unpack the half a dozen specific orders contained in it.

The author is a former senator

The verdict delivered by Justice Mushir Alam and Justice Qazi Faez Isa also opens enormous possibilities for the parliament and state institutions. Consider.

First, the government was told that the protesters of the Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan (TLP) dharna must be proceeded against under the Pakistan Penal Code, the Anti-Terrorism Act, 1997 or the Prevention of Electronic Crimes Act, 2016 and brought to justice.

Second, it asked the Election Commission of Pakistan to proceed against a political party (TLP) that does not comply with laws governing political parties.

Third, touching upon complaints of media bodies, it declared illegal the advice of self-censorship to suppress independent viewpoints and asked Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA) to take action in complaints against interference in broadcasts and delivery of publications in cantonment areas and Defence Housing Authorities. If such interference was done on the behest of others, then PEMRA should report it to the authorities concerned, the judgement said. Tactics such as directions to media organizations as to who should be hired or fired were also declared illegal.

Fourth, with regards to reining in state intelligence agencies and ensuring transparency and rule of law, the court ordered making legislation to clearly stipulate the respective mandates of the intelligence agencies.

Fifth, reminding the armed forces of constitutional restrictions on engaging in politicking, the court ordered the Defence Ministry and respective chiefs of the Army, Navy and Air Force to penalise the personnel found to have violated their oath. “We must not allow the honour and esteem due to those who lay down their lives for others to be undermined by the illegal actions of a few,” it presciently observed.

Sixth, copies of the judgment were sent for information and compliance to all quarters, namely the relevant federal secretaries, the three services chiefs, provincial chief secretaries, the election commission, PEMRA and the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) among others.

It is true that the observations made by the SC can be heard almost daily from civil society organizations in seminars and public discussions. But the difference lies in the authenticity and weight lent to such observations when they come from Supreme Court, and the clear cut directions given by the court on the steps to be taken. Failure on the part of the government and relevant bodies is sure to attract contempt provisions.

By making this declaration, the SC has opened doors for the parliament to enact appropriate legislation for determining the mandate of intelligence agencies. A great opportunity has been provided to the parliament and the state’s democratic institutions to end the era of contempt of the people so blatantly manifested in manipulated power transfer, distorted civil-military relations, backdoor re-engineering of political landscape and stifling dissent.

Sometime back, an aborted attempt was made in the Senate to bring ISI under the legislative framework. As a consequence of the SC order, the Upper House now has a unique opportunity to revive the aborted bid of the past. If the parliament fails to enact such legislation, it will have no one to blame except itself.

The directions to the Defence Ministry and the three services chiefs to penalise the personnel of the forces found to have violated their oath is a breath of fresh air. It will be naive to expect that those who violated their oath will be actually penalised anytime soon. The important thing is not to penalise them instantly. It is the opportunity to set in motion the process of accountability. The two-decades-old petition of Air Marshal Asghar Khan may still not have brought the perpetrators to justice, but it will be unfair to say that it has served no useful purpose. The ghost of late Asghar Khan continues to haunt wrongdoers and sends a warning signal to would-be perpetrators. That in itself is no small achievement.

The court’s orders to PEMRA to take action against cable operators who shut broadcasts and those who interfered with the distribution of publications in cantonment areas is also highly significant for the potential it holds. PEMRA is now under obligation to investigate the matter and its failure will give an opportunity to rights activists to agitate the matter inside and outside the courts. The possibilities indeed are exciting.

There is lot in the verdict for restoration of freedom of expression and dissent. The court observed that PEMRA had failed to protect legitimate rights of its licensed broadcasters. Broadcasts by Dawn and Geo were interrupted in DHAs and this interruption was duly acknowledged by PEMRA as it failed to take action and ‘sadly looked the other way.’ On two occasions, PEMRA was asked as to who was responsible. Its representatives professed ignorance, the court noted.

This is not only a stinging indictment of PEMRA, it also places in the hands of media organizations a powerful tool to regain their lost freedoms.

The ball is now in the court of political parties, the parliament, media organisations and civil society organisations. For far too long, political governments have bent over backwards to woo anti-democratic forces for elusive political stability. Opposition parties, on the other hand, have colluded with these anti-democracy forces to bring down the government. In between, the anti-democratic forces have jeered at politicians and made hay while the sun shone for them.

It will be wrong to see the verdict as a report by the Judicial Commission that makes some broad-based recommendations and may not have the same enforcement authority as that of a court order. There are specific orders in the Faizabad dharna case verdict that have to be complied with and failure to do so will entail consequences.

The SC verdict offers so much but only if the political class and civil society grasped its significance, mended their ways and begin to unpack the half a dozen specific orders contained in it.

The author is a former senator