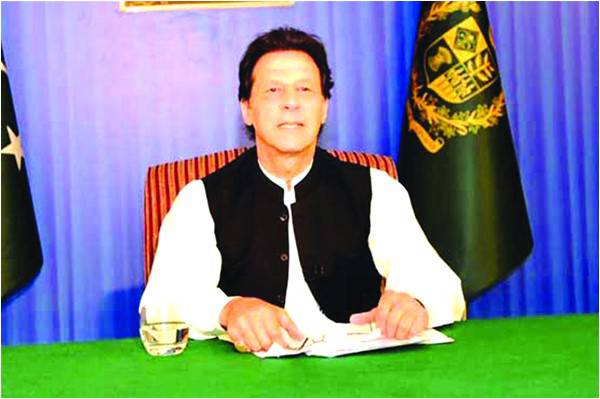

This is written a week after Prime Minister Imran Khan’s maiden address to the Pakistan nation. As far as I can make out from the English press summaries, it was, rhetorically, a melodic start; the new PM hit all the right notes. It may have also been the most ambitious vision for Pakistan since its founding father, Mohammed Ali Jinnah, almost exactly 71 years earlier, envisioned the newly-created and struggling state of Pakistan as a secular, inclusive, prosperous democratic nation which welcomed minorities of any stripe fleeing majoritarian oppression. Taken literally, Khan’s vision would rival John Winthrop’s 1630 definition of a perfect “shining city on a hill,” a nation that supports itself, with a frugal elite that pays its taxes and shares its wealth with the poor, that educates its young and sees to the health of its inhabitants, in which the rule of law is supreme, and compassion and merit are the norms. That is a lot to wish, and certainly not an overnight or easy task.

I write this as an outsider, looking in at a Pakistan I have followed closely for over 20 years and for which I have often wished a leader cut from a new mold that would lead it out of the path of mediocrity it has followed much of that time, much to the chagrin, I think of the many Pakistanis I know very well and admire greatly. The problem is that leaders who promise such change often are beholden to a status quo mindset, and if they weren’t would likely be authoritarian demagogues.

For a politician who campaigned mainly as a populist, using corruption as his main whipping post, it was reassuring to hear that Khan does seem to grasp much of the disastrous economic and social conditions into which Pakistan and its people have fallen in those 71 years. Whether he grasps also the main political constraint—the civilian-military power struggle—is not clear. He said nothing about that, at least not in the summaries I saw, and that would be just good politics at this point given the multitude of other problems he faces including, to start with, the wreck of an economy.

My sense from the summaries I read, is that he offered a very long term vision of a fully reformed and modernized Pakistan (though he would probably deny that what he envisions is “modernisation” which has come to be thought of by many Pakistanis as synonymous with westernisation), a Pakistan that can prosper in the 21st century. However, the address leaves me uncertain as to whether my version of his vision is correct, and if so, whether he is the leader who can lead Pakistan to the road taking it to that vision.

It seemed clear to me the economy is his highest priority at the beginning and that strikes me as a correct decision. But how he will go about reforming the economy and pulling Pakistan out of the balance of payments crisis not only seemed quite vague and naïve, but frankly contradictory and dangerously uninformed. Some of it was clearly right out of the populists’ playbook: emphasizing frugality, both on the part of the government, and by the well-off elite, including an exhortation that they pay all their taxes as well as share their wealth with the poor. He came close to pledging that he would not look for financing from abroad (read from the IMF) saying that “when these people give money, they attach conditions to it,” but that may be his populist instinct talking, and the facts of the situation may change his mind.

But he has the right idea for the long-run, explaining at the beginning of his demurral about borrowing that he wants to rebuild the economy using resources generated within Pakistan not via external loans. It is unclear how he views the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) in this context, of which I found no mention in the English summaries of his speech, where a planned $60 billion of Chinese loans, at fairly high interest rates, will build power plants and accommodating infrastructure, which will supposedly link to and catalyse the national economy. If this also seems contradictory, I think it is too much to ask a politician who has just taken office, and is without experience and extensive knowledge of many issues, and faces a multitude if immediate problems, to be perfectly consistent in his initial speech on his general approach to those issues.

One hopeful sign is his understanding that one of Pakistan’s main economic problems—perhaps the main one—is that it is a very under-taxed country, which has failed to live within its domestic resource limits for many decades now. As readers know the tax/revenue ratio in Pakistan has been historically very low, well below what it should be. Despite this acknowledged fact (even at some point by governing political parties), it remains, despite a recent modest increase to about 12 percent according to the IMF (better than what I remembered), still well below countries of comparative size and level of development. The PM went on at some length about the necessity of people paying their taxes. I assume that here he is talking about more than just people being more honest, but about real reform which, among other things changes the tax structure and gives the tax authorities more information as to income and tax liability. Obliquely, the PM referred to fixing the tax administration to give it more credibility with taxpayers, which should mean finding and rooting out the corruption in the tax collection system. That would fit in well with his anti-corruption program.

There are many other quibbles one might raise about this address to the nation, as like most such addresses it was short on detail and long on sentiment and symbol. It was, after all, a political speech. For example, I think the measures he outlined to cut government expenses are symbolic, as the many excesses he lists to be cut or the assets to be sold (like armoured cars) are symbols of the inequality and inequities between the elite and the common folk. This monkish approach may be effective politically but it is unlikely to add much in the way of resources to the government’s coffers. Recuperating monies held abroad is unlikely to produce much either, although if Khan were to prove a real reformer and a leader that would bring a sense of certainty and security—which might take a decade or so—I suspect that overseas holdings of many Pakistanis would be repatriated.

I have wondered for a long time about whether Pakistan would ever find the political will to political and economic reform. I do not see how it can survive the pressures of the coming decades drifting along as it has for the past 20 years. If its politicians and their military partners do not find the will to reform, the surge of uneducated and probably unemployed young people in what we call the demographic surge will certainly bring revolution at some point. And the scarier question is who will be leading that surge? Imran Khan’s initial address to the nation on August 19 doesn’t tell me whether he is going to lead the present dual political leadership real reform agenda or not. It can be read either way. We have to wait to see what he does in the next few months, up to perhaps a year, before we know if it is real or just another imitation of the past.

The author is a senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC, and a former US diplomat who was ambassador to Pakistan and Bangladesh

I write this as an outsider, looking in at a Pakistan I have followed closely for over 20 years and for which I have often wished a leader cut from a new mold that would lead it out of the path of mediocrity it has followed much of that time, much to the chagrin, I think of the many Pakistanis I know very well and admire greatly. The problem is that leaders who promise such change often are beholden to a status quo mindset, and if they weren’t would likely be authoritarian demagogues.

For a politician who campaigned mainly as a populist, using corruption as his main whipping post, it was reassuring to hear that Khan does seem to grasp much of the disastrous economic and social conditions into which Pakistan and its people have fallen in those 71 years. Whether he grasps also the main political constraint—the civilian-military power struggle—is not clear. He said nothing about that, at least not in the summaries I saw, and that would be just good politics at this point given the multitude of other problems he faces including, to start with, the wreck of an economy.

My sense from the summaries I read, is that he offered a very long term vision of a fully reformed and modernized Pakistan (though he would probably deny that what he envisions is “modernisation” which has come to be thought of by many Pakistanis as synonymous with westernisation), a Pakistan that can prosper in the 21st century. However, the address leaves me uncertain as to whether my version of his vision is correct, and if so, whether he is the leader who can lead Pakistan to the road taking it to that vision.

It seemed clear to me the economy is his highest priority at the beginning and that strikes me as a correct decision. But how he will go about reforming the economy and pulling Pakistan out of the balance of payments crisis not only seemed quite vague and naïve, but frankly contradictory and dangerously uninformed. Some of it was clearly right out of the populists’ playbook: emphasizing frugality, both on the part of the government, and by the well-off elite, including an exhortation that they pay all their taxes as well as share their wealth with the poor. He came close to pledging that he would not look for financing from abroad (read from the IMF) saying that “when these people give money, they attach conditions to it,” but that may be his populist instinct talking, and the facts of the situation may change his mind.

But he has the right idea for the long-run, explaining at the beginning of his demurral about borrowing that he wants to rebuild the economy using resources generated within Pakistan not via external loans. It is unclear how he views the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) in this context, of which I found no mention in the English summaries of his speech, where a planned $60 billion of Chinese loans, at fairly high interest rates, will build power plants and accommodating infrastructure, which will supposedly link to and catalyse the national economy. If this also seems contradictory, I think it is too much to ask a politician who has just taken office, and is without experience and extensive knowledge of many issues, and faces a multitude if immediate problems, to be perfectly consistent in his initial speech on his general approach to those issues.

One hopeful sign is his understanding that one of Pakistan’s main economic problems—perhaps the main one—is that it is a very under-taxed country, which has failed to live within its domestic resource limits for many decades now. As readers know the tax/revenue ratio in Pakistan has been historically very low, well below what it should be. Despite this acknowledged fact (even at some point by governing political parties), it remains, despite a recent modest increase to about 12 percent according to the IMF (better than what I remembered), still well below countries of comparative size and level of development. The PM went on at some length about the necessity of people paying their taxes. I assume that here he is talking about more than just people being more honest, but about real reform which, among other things changes the tax structure and gives the tax authorities more information as to income and tax liability. Obliquely, the PM referred to fixing the tax administration to give it more credibility with taxpayers, which should mean finding and rooting out the corruption in the tax collection system. That would fit in well with his anti-corruption program.

There are many other quibbles one might raise about this address to the nation, as like most such addresses it was short on detail and long on sentiment and symbol. It was, after all, a political speech. For example, I think the measures he outlined to cut government expenses are symbolic, as the many excesses he lists to be cut or the assets to be sold (like armoured cars) are symbols of the inequality and inequities between the elite and the common folk. This monkish approach may be effective politically but it is unlikely to add much in the way of resources to the government’s coffers. Recuperating monies held abroad is unlikely to produce much either, although if Khan were to prove a real reformer and a leader that would bring a sense of certainty and security—which might take a decade or so—I suspect that overseas holdings of many Pakistanis would be repatriated.

I have wondered for a long time about whether Pakistan would ever find the political will to political and economic reform. I do not see how it can survive the pressures of the coming decades drifting along as it has for the past 20 years. If its politicians and their military partners do not find the will to reform, the surge of uneducated and probably unemployed young people in what we call the demographic surge will certainly bring revolution at some point. And the scarier question is who will be leading that surge? Imran Khan’s initial address to the nation on August 19 doesn’t tell me whether he is going to lead the present dual political leadership real reform agenda or not. It can be read either way. We have to wait to see what he does in the next few months, up to perhaps a year, before we know if it is real or just another imitation of the past.

The author is a senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center in Washington DC, and a former US diplomat who was ambassador to Pakistan and Bangladesh