“Jandar de Raat” is a well-known phrase spoken locally in villages in Kashmir – for situations when one has to spend a night somewhere out without any positive engagement and definitely without bed.

But it had kept me confused for long. What exactly does one mean by “Jandar de raat”? My curiosity compelled me to ask a friend who first smiled and later asked me to spare a night to investigate for myself the actual meaning of “Jandar de raat”.

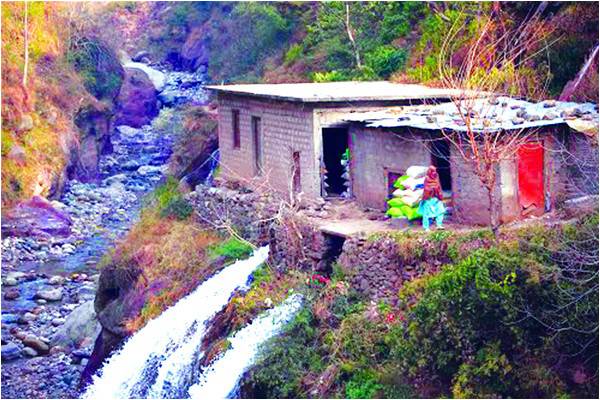

That night finally arrived. We both traveled to a neighbouring village known as Tarkhan Bandi, near Boar Muzaffar Shah, a beautiful village on the outskirts of the capital city Muzaffarabad and my hometown.

We find centuries-old water-run flour mills known as jandars. Many people are standing in a queue with their bags of wheat or maize, waiting for their turn. My friend tells me that many of them came from far-flung areas and they will have to wait for their turn till morning. This is the reason for calling it “Jandar de Raat”

So does it mean a night spent at local water-run flour mill? I spontaneously ask just this and get a big laugh from him in response.

I realise it is a great place for interaction, for telling and listening to stories from people who came from various remote areas. The point here is to just kill time and help each other avoid feeling too sleepy.

Time passes and it passes so fast. I have not found such gatherings, or such places to meet and interact, elsewhere. Jandars are themselves a thing of the past, for the most part.

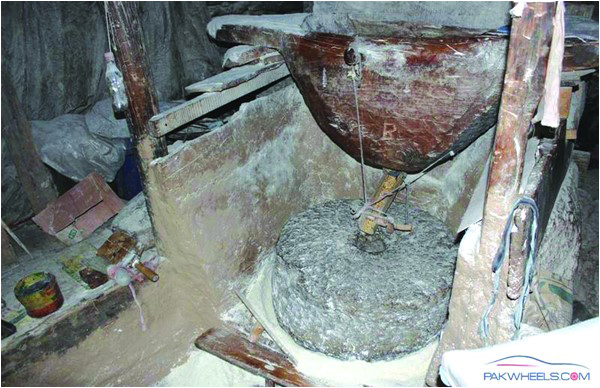

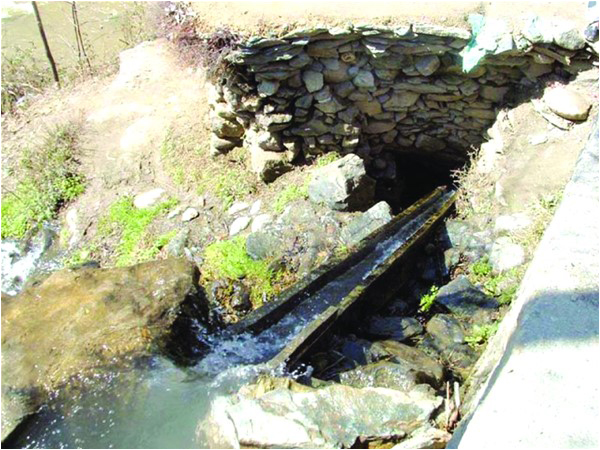

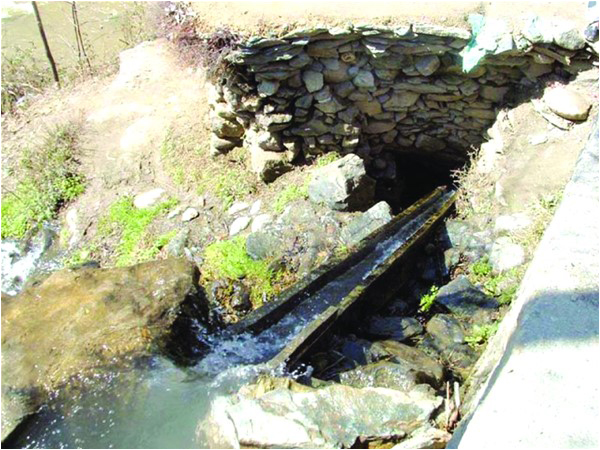

Many of my readers would have no information about the traditional mills powered by fast-flowing water from the nearby stream or river, which turns the heavy grindstone to produce flour.

Many old people in villages still prefer to grind their wheat in the traditional water-run mills due to a wide-held belief that wheat from jandars is of better quality and tastes better than mass-produced flour.

Another interesting thing is that owners of these traditional water mills do not charge money for grinding wheat. They take a share from the ground flour.

I ask the reason for this preference to Chacha Lal Hussain. He explains: “Flour ground in water mills remains safe from insects and other pests for many months. That is why so many people are waiting with sacks of wheat to be ground”

Traditional water mills are environment-friendly and do not consume fuel or electricity. They require a single small room and a little investment. The one and only disadvantage that I observed is slow processing. It takes hours to grind a kilogram of wheat or maize.

The owner of a jandar – I forgot his name – once told me that he has been operating a water mill for decades and charges very nominal amounts of grain. He says machine-run flour mills are charging much more as compared to the local traditional mills.

He too, obviously, is of the view that flour from such mills tastes better than that from modern mills.

I believe Jandars could be used as small tool to tackle the country’s energy shortage.

The idea is simple: each of these mills could be connected to a small-scale turbine to generate free, clean electricity in nearby villages and the local areas could become energy self-reliant.

Mr. Khaki, owner of a locally installed turbine at a jandar in Sarli Sacha village of Muzaffarabad district, tells me that water channeled for watermills can be used to produce electricity for a whole village.

“We experimented with it and we are now providing electricity to the whole village at cheap rates without any interruption. Sometimes we have surplus energy, which could be fed to the national grid”, he says.

Mr. Khaki installed a homemade turbine and a small transferring motor alongside his jandar. The generator was connected to lights by copper wiring recycled from telephone cables. The whole project cost Khaki six lakh (600,000) rupees.

Although work on a number of mega hydropower projects in Azad Jammu and Kashmir is underway, it still needs the government and nongovernmental organisations to help. And part of this could be to help traditional millers install small energy production units alongside their jandars.

Power generation through watermills and small projects will ultimately reduce pressure on the forests which are being cut ruthlessly down for wood as fuel.

Experts believe that it requires a maximum investment of five to seven lakh (5-700,000) rupees on the turbine, the motor and the pipe.

Mubashar Naqvi is a freelance writer based in Muzaffarabad. He can be contacted on Twitter via @SMubasharNaqvi

But it had kept me confused for long. What exactly does one mean by “Jandar de raat”? My curiosity compelled me to ask a friend who first smiled and later asked me to spare a night to investigate for myself the actual meaning of “Jandar de raat”.

That night finally arrived. We both traveled to a neighbouring village known as Tarkhan Bandi, near Boar Muzaffar Shah, a beautiful village on the outskirts of the capital city Muzaffarabad and my hometown.

***

We find centuries-old water-run flour mills known as jandars. Many people are standing in a queue with their bags of wheat or maize, waiting for their turn. My friend tells me that many of them came from far-flung areas and they will have to wait for their turn till morning. This is the reason for calling it “Jandar de Raat”

So does it mean a night spent at local water-run flour mill? I spontaneously ask just this and get a big laugh from him in response.

I realise it is a great place for interaction, for telling and listening to stories from people who came from various remote areas. The point here is to just kill time and help each other avoid feeling too sleepy.

Time passes and it passes so fast. I have not found such gatherings, or such places to meet and interact, elsewhere. Jandars are themselves a thing of the past, for the most part.

Many of my readers would have no information about the traditional mills powered by fast-flowing water from the nearby stream or river, which turns the heavy grindstone to produce flour.

Many old people in villages still prefer to grind their wheat in the traditional water-run mills due to a wide-held belief that wheat from jandars is of better quality and tastes better than mass-produced flour.

Another interesting thing is that owners of these traditional water mills do not charge money for grinding wheat. They take a share from the ground flour.

I ask the reason for this preference to Chacha Lal Hussain. He explains: “Flour ground in water mills remains safe from insects and other pests for many months. That is why so many people are waiting with sacks of wheat to be ground”

Traditional water mills are environment-friendly and do not consume fuel or electricity. They require a single small room and a little investment. The one and only disadvantage that I observed is slow processing. It takes hours to grind a kilogram of wheat or maize.

The owner of a jandar – I forgot his name – once told me that he has been operating a water mill for decades and charges very nominal amounts of grain. He says machine-run flour mills are charging much more as compared to the local traditional mills.

Mr. Khaki, owner of a locally installed turbine at a jandar in Sarli Sacha village of Muzaffarabad district, tells me that water channeled for watermills can be used to produce electricity for a whole village

He too, obviously, is of the view that flour from such mills tastes better than that from modern mills.

I believe Jandars could be used as small tool to tackle the country’s energy shortage.

The idea is simple: each of these mills could be connected to a small-scale turbine to generate free, clean electricity in nearby villages and the local areas could become energy self-reliant.

Mr. Khaki, owner of a locally installed turbine at a jandar in Sarli Sacha village of Muzaffarabad district, tells me that water channeled for watermills can be used to produce electricity for a whole village.

“We experimented with it and we are now providing electricity to the whole village at cheap rates without any interruption. Sometimes we have surplus energy, which could be fed to the national grid”, he says.

Mr. Khaki installed a homemade turbine and a small transferring motor alongside his jandar. The generator was connected to lights by copper wiring recycled from telephone cables. The whole project cost Khaki six lakh (600,000) rupees.

Although work on a number of mega hydropower projects in Azad Jammu and Kashmir is underway, it still needs the government and nongovernmental organisations to help. And part of this could be to help traditional millers install small energy production units alongside their jandars.

Power generation through watermills and small projects will ultimately reduce pressure on the forests which are being cut ruthlessly down for wood as fuel.

Experts believe that it requires a maximum investment of five to seven lakh (5-700,000) rupees on the turbine, the motor and the pipe.

Mubashar Naqvi is a freelance writer based in Muzaffarabad. He can be contacted on Twitter via @SMubasharNaqvi