The legend of Anarkali lives on. She must have been a woman of rare beauty and charm to have caught the eye of the Emperor of all Mughal Emperors, Akbar. He was well into his middle age – and must have been sated after a couple of wives and umpteen courtesans. And he was also not known for leading a depraved lifestyle. Yet she managed to entrance him. Then she totally captured the heart of his spoilt son Jahangir, the future Emperor of all India. The father told his son to lay off, but the crown prince was so smitten that he threw all caution to the winds and decided to wed her. This drew the wrath of the most powerful Emperor of India. He was still infatuated with her and grudged her preference for his son. Both men had no dearth of women available in the Harem or outside. Yet they both fell for the same person. She had a magic that clearly no one else had.

Despite the wrath of his father Jahangir pursued his affair with Anarkali recklessly. The story as it ends is known to all – an angry Emperor ordered her to be buried alive. Apparently she died singing her heart out, and so began the legend of Anarkali. When the father died and Jahangir became the Emperor, he built an imposing tomb in her memory. This is the “Makbara” which is now located just behind the Civil Secretariat in Lahore. He exhumed her body from its old burial ground and placed it there at the Makbara. The building is an imposing stone structure with a large dome in the centre. There are eight turrets and eight wide passages leading off from the central dome. The grave is now in a west-facing passage with a basement where the actual body lies. It is an elegant white marble affair carved with the attributes of the Almighty in typical Mughal fashion. There lies Anarkali – desired by two Mughal emperors, a father and a son.

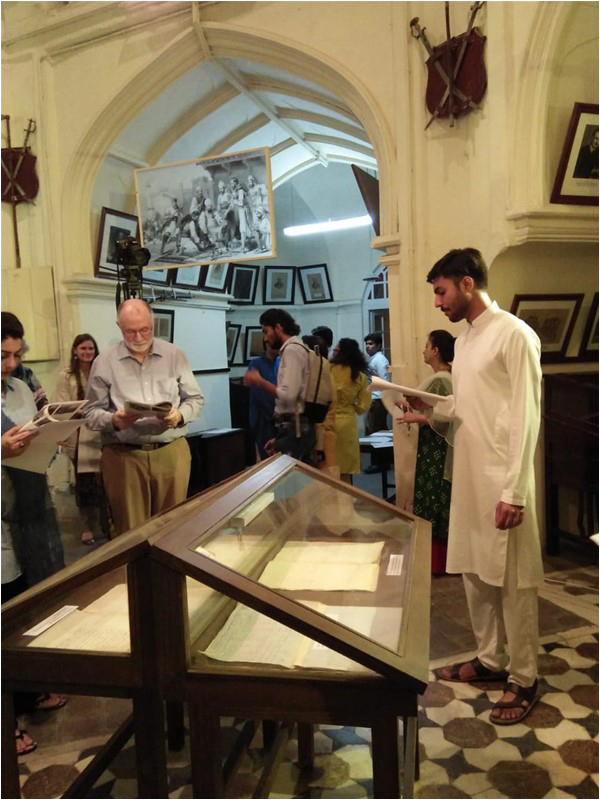

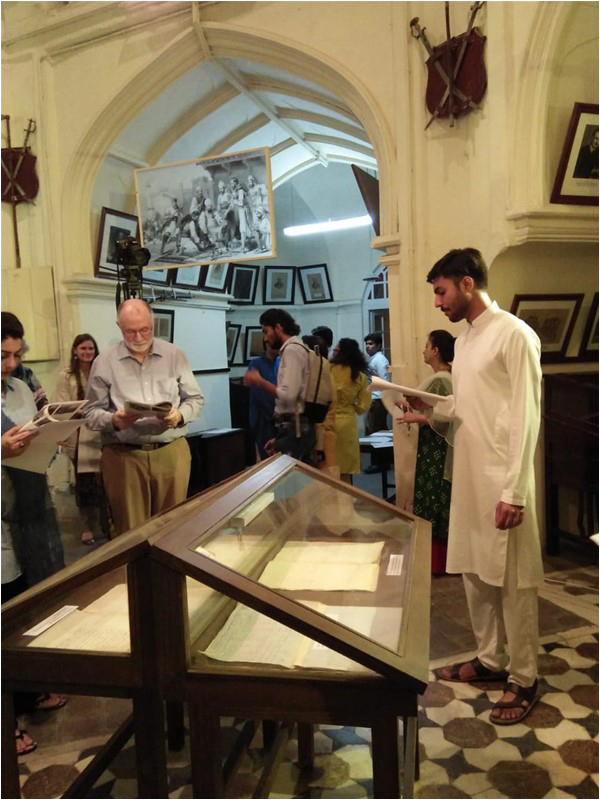

This romantic grave is surrounded by the archives of the Government of Punjab. Sombre wooden shelves house the thousands of letters, missives, orders and reports of this turbulent period, as the British Raj settled over what is now Pakistan. The earliest archives are of the Sikh period, mostly in Persian, which are still to be translated. Then came the Raj and the Lawrence brothers with their immense charm and imperial ambitions. They settled the Punjab, and laid out the foundations of the British Raj over this part of the Subcontinent.

What was on display for us last week was the “Mutiny” of 1857 as seen through British eyes. Titled ‘Fear and Vengeance in 1857’, it had been organised by Mr. Yaqoob Bangash who is putting his D. Phil at Oxford to good use in the service of the Government of Punjab. He and Waqas Halim have launched this project with financial help from the Punjab Information and Technology Board. The Punjab Archives Digitilasation Project has been equipped with modern tools to digitalise the archives. Hopefully, these will then be available to academics and historians to research and enjoy. There is a wealth of information in these archives as the British sarkaar (government) loved to chronicle every event and action. During the Mutiny they set up kangaroo courts to try and hang or blow up any one who had revolted – or who they suspected might revolt. They even chronicled these kangaroo courts. An edict issued by the army declared that any “European” officer could set up a court martial consisting of not less than five officers and “any sentence of death or other punishment may be given if a majority concur.” This was duly notified as ACT XVII by the Adjutant General of the army at “Umballa” to Major General Reed and the Chief Commissioner “Rawalpindee”.

Contrast this to the well established practice of the Mughal, Sikh or Maratha armies, who would march into a village or town and summarily execute a substantial part of the local population as punishment for revolt or simply to spread terror.

The British did something similar; but they recorded it as well. The minutes of one such “court martial” record the names of twelve persons. There is one person per line in the register. After each name comes his parentage, and the death penalty for treason. That is all. Then follow the names of the other eleven unfortunate sepoys and so on so forth. To top it all off, an etching of one such event is also preserved. It appears that you could do what you like as long as you recorded it!

There are a number of etchings of the life of a British officer in those times. There are scenes of native sepoys being blown up by cannons or being strung up from the branches of trees with the bodies left hanging as an example to others. There are scenes of British families hiding in the jungle from the rebels – the ladies wearing full-length Victorian dresses with bonnets, clutching children to their bosoms.

There are, of course, reports to Rawalpindi from the smaller stations asking for more European troops as reinforcements. There are instructions from the top, such as the one of the courts. The prized edict, as read out by Ms. Sadaf, a curator, with a twinkle in her eye, is re produced below in full:

“Rawalpindee 19th.May 1857

Circular to all Commissioners.

Sir

I am writing this circular to request that you will call upon all native editors of newspapers in V. division to refrain from publishing any rumours pertaining to the mutiny in the army calculated to excite alarm.

I suppose it applies in substance even today in Pakistan!

A few years ago William Dalrymple, the well known historian, came to Lahore and wanted to research the Afghan Wars. He said that there was such a wealth of material in the Government of Punjab Archives that he wanted to spend at least six months in Lahore. He said that all the missives, reports and desperate appeals for help from the British army in Afghanistan are preserved here.

Mr. Bangash explained that once the process of digitalisation is completed, any researcher can obtain the information they seek – e.g. If you wish to know what were the areas used for cotton-growing, the quantity grown, etc. you could simply ask the system to give you all the relevant texts.

One imagines the British reports from Central Asia, Afghanistan, Persia, and Jammu-Kashmir are all preserved here – waiting for someone to put them together to make for fascinating reading.

Despite the wrath of his father Jahangir pursued his affair with Anarkali recklessly. The story as it ends is known to all – an angry Emperor ordered her to be buried alive. Apparently she died singing her heart out, and so began the legend of Anarkali. When the father died and Jahangir became the Emperor, he built an imposing tomb in her memory. This is the “Makbara” which is now located just behind the Civil Secretariat in Lahore. He exhumed her body from its old burial ground and placed it there at the Makbara. The building is an imposing stone structure with a large dome in the centre. There are eight turrets and eight wide passages leading off from the central dome. The grave is now in a west-facing passage with a basement where the actual body lies. It is an elegant white marble affair carved with the attributes of the Almighty in typical Mughal fashion. There lies Anarkali – desired by two Mughal emperors, a father and a son.

An edict issued by the army declared that any "European" officer could set up a court martial consisting of not less than five officers and "any sentence of death or other punishment may be given if a majority concur"

This romantic grave is surrounded by the archives of the Government of Punjab. Sombre wooden shelves house the thousands of letters, missives, orders and reports of this turbulent period, as the British Raj settled over what is now Pakistan. The earliest archives are of the Sikh period, mostly in Persian, which are still to be translated. Then came the Raj and the Lawrence brothers with their immense charm and imperial ambitions. They settled the Punjab, and laid out the foundations of the British Raj over this part of the Subcontinent.

What was on display for us last week was the “Mutiny” of 1857 as seen through British eyes. Titled ‘Fear and Vengeance in 1857’, it had been organised by Mr. Yaqoob Bangash who is putting his D. Phil at Oxford to good use in the service of the Government of Punjab. He and Waqas Halim have launched this project with financial help from the Punjab Information and Technology Board. The Punjab Archives Digitilasation Project has been equipped with modern tools to digitalise the archives. Hopefully, these will then be available to academics and historians to research and enjoy. There is a wealth of information in these archives as the British sarkaar (government) loved to chronicle every event and action. During the Mutiny they set up kangaroo courts to try and hang or blow up any one who had revolted – or who they suspected might revolt. They even chronicled these kangaroo courts. An edict issued by the army declared that any “European” officer could set up a court martial consisting of not less than five officers and “any sentence of death or other punishment may be given if a majority concur.” This was duly notified as ACT XVII by the Adjutant General of the army at “Umballa” to Major General Reed and the Chief Commissioner “Rawalpindee”.

Contrast this to the well established practice of the Mughal, Sikh or Maratha armies, who would march into a village or town and summarily execute a substantial part of the local population as punishment for revolt or simply to spread terror.

The British did something similar; but they recorded it as well. The minutes of one such “court martial” record the names of twelve persons. There is one person per line in the register. After each name comes his parentage, and the death penalty for treason. That is all. Then follow the names of the other eleven unfortunate sepoys and so on so forth. To top it all off, an etching of one such event is also preserved. It appears that you could do what you like as long as you recorded it!

There are a number of etchings of the life of a British officer in those times. There are scenes of native sepoys being blown up by cannons or being strung up from the branches of trees with the bodies left hanging as an example to others. There are scenes of British families hiding in the jungle from the rebels – the ladies wearing full-length Victorian dresses with bonnets, clutching children to their bosoms.

There are, of course, reports to Rawalpindi from the smaller stations asking for more European troops as reinforcements. There are instructions from the top, such as the one of the courts. The prized edict, as read out by Ms. Sadaf, a curator, with a twinkle in her eye, is re produced below in full:

“Rawalpindee 19th.May 1857

Circular to all Commissioners.

Sir

I am writing this circular to request that you will call upon all native editors of newspapers in V. division to refrain from publishing any rumours pertaining to the mutiny in the army calculated to excite alarm.

- They should be urged on the other hand to endeavour to allay the general meanings, and to point out the folly of the present conduct of the sepoys.

- These admonitions should be given privately, but if they fail in their object, you are authorised at once to sequestrate the paper and require heavy security from the editor, failing which, he should be placed in confinement.

- If again any editor shows an inclination to support the Europeans, he may be furnished with such items of intelligence as can be judicially established.”

I suppose it applies in substance even today in Pakistan!

A few years ago William Dalrymple, the well known historian, came to Lahore and wanted to research the Afghan Wars. He said that there was such a wealth of material in the Government of Punjab Archives that he wanted to spend at least six months in Lahore. He said that all the missives, reports and desperate appeals for help from the British army in Afghanistan are preserved here.

Mr. Bangash explained that once the process of digitalisation is completed, any researcher can obtain the information they seek – e.g. If you wish to know what were the areas used for cotton-growing, the quantity grown, etc. you could simply ask the system to give you all the relevant texts.

One imagines the British reports from Central Asia, Afghanistan, Persia, and Jammu-Kashmir are all preserved here – waiting for someone to put them together to make for fascinating reading.