The straw hut where Masi Sakina lives with her 12 orphaned children is situated near Roopa Marri, which has been Sindh’s capital during the era of the Soomra dynasty. The village, namely Kandero Mallah, is deprived of all facilities for the most basic human needs. Or, in other words, one can say that it is hard to find the footsteps of life in this village.

In the whole village, there is not a single drop of fresh water available. There is no electricity. There is no school. In fact, the very concept of schooling, study or books doesn’t exist for many of the people living here. The inhabitants have the haziest idea, if at all, as to what books are for. When I asked a girl Kalsoom if she were to be educated, as to what she would like to be, she didn’t have much of a response for me. She can’t imagine what an education is, what it entails or what it could potentially do for someone.

The village, Kandero Mallah, consists of 55 households of the Mallah clan and the population of this village is around 500 people. Akram Mallah, 35 years old, is the only person in the entire village who is educated. He could barely pass Matriculation exams from Seerani High School, which is situated around 20 kilometres from this remote village. Nevertheless, Akram Mallah is their teacher, doctor, lawyer and generally the only source of information about the world outside for his fellow villagers.

The people of the village Kandero Mallah use to vote for the party of ‘Shaheeds’ (martyrs) for years. But until today, not a single elected representative has visited the village. Not a single member of a provincial or national assembly has tried to know more about the people of the village. Surprisingly, they don’t have any complain about anything from anyone. For them, Javed Khaskheli is a saviour because he intervened in this village through a nongovernmental organisation, the Hilal Ahmer Pakistan (Red Crescent). Javed Khaskheli not only supported them by imparting various trainings but also tried to provide direct material assistance – by providing sheep, goats and some other useful belongings for the deprived people of the village.

And so it happens that on a sweltering hot day in May, I along with Masood Lohar and Ameer Mandhro reach the village after traversing the barren lands of Roopa Marri. The deprivation, of course, is the first thing to strike me. I find myself thinking that the young women I see, 20 to 25 years old at most, look like much, much older women.

Looking at the local children, I observe something very odd. They don’t seem to be playing. The little girls have no concept of playing with dolls. The little boys have no notion of sports.

I find myself wondering if the people of Kandero Mallah dare to dream.

But I do know for certain that this terrain of the ‘Larr’ region was once amongst the most eye-catching and fertile areas of Sindh. There would have been life, happiness and prosperity here – that, for me, is the only explanation for why the Soomra dynasty would make this place their capital of Sindh. Once upon a time, too, this region would have been a trading hub and conquerors like Alauddin Khilji attacked it in their greed, knowing that they would find much wealth.

But what wealth is to be found here right now?

Hand pumps have stopped pumping fresh water. Rivers, ponds and other fresh water bodies have dried up. There is no concept of flowing water. It’s hard to find a green piece of land in the entire region. The only tree left here in this part of the country is the “Devi” or Mesquite – which is a source of income for these people and fodder for their livestock. I do not know what meaning this tree has in the rest of the Indian Subcontinent, but for the people of Sindh’s coastal belt – including the villagers of Kandero Mallah – the tree has proved to be a true Devi (goddess) because they sell its wood and earn some money.

The people, nevertheless, if asked about their circumstances, always respond with “We are thankful to Almighty Allah that He shields us even in these harsh circumstances”. It makes me want to rethink my own priorities and view of life.

What they call their home is actually a number of straw huts which are mercilessly bathed by the sun’s heat. The scorching sunrays are observable even while sitting inside a hut. I’m not sure if there is a single place to breathe away from the raging heat in the entire village during summers.

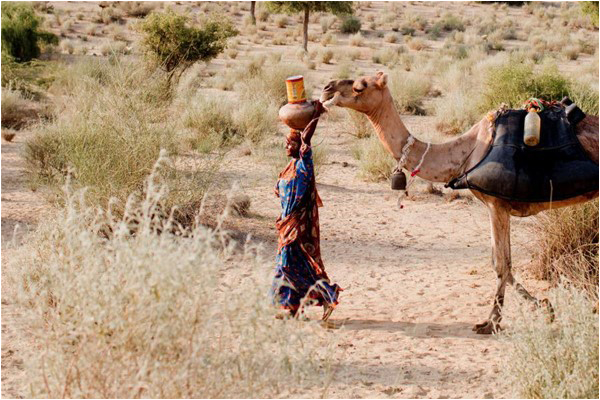

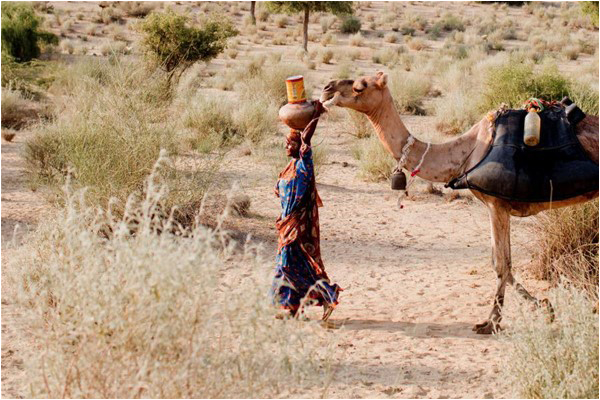

Women carrying pitchers of water walk for several kilometres to get drinking water. They do not appear very concerned that elections are close at hand. They are also unconcerned about the changing of governments or the general circumstances of the country. Democracy and dictatorship are equally irrelevant for the villagers of Kandero Mallah. They don’t ask anyone for anything. Even the PPP’s catchphrase from the Bhutto era, “Roti, kapra aur makaan” (Bread, clothing and housing) means little to them. their grief into power.

The call to prayer reaches our ears. Masi Sakina stands up, leaves the conversation in the middle and informs me: “Son! It is Allah’s call, so I have to go to offer prayer.”

Incidentally, there is no mosque in this village – though there are many mosques and madrassahs built by religious organisations in the region more generally.

The 1999 cyclone brought devastation in southern Sindh – and in doing so, it changed the entire geography of the Larr region. This village also paid a heavy price during that calamity. The fisherfolk of the village, who were at sea on that day, haven’t come back till this day. No one knows what became of them. The people of the village also lost their livestock, huts and many other belongings in the cyclone. The fresh water which once used to reach in this region also stopped after that lethal cyclone.

I often think that if those ‘technical’ people who speak in favour of the Kalabagh Dam were to come and spend some hours in Kandero Mallah, their entire scientific philosophy and engineering might stop working.

I find myself thinking how unfair it is that in an era when Google Maps can be used to find the exact location of any place in the world, no app can mark the pain of the residents of village Kandero Mallah.

The writer is a freelancer based in Badin, Sindh. He can be reached at abbaskhaskheli110@gmail.com

In the whole village, there is not a single drop of fresh water available. There is no electricity. There is no school. In fact, the very concept of schooling, study or books doesn’t exist for many of the people living here. The inhabitants have the haziest idea, if at all, as to what books are for. When I asked a girl Kalsoom if she were to be educated, as to what she would like to be, she didn’t have much of a response for me. She can’t imagine what an education is, what it entails or what it could potentially do for someone.

The village, Kandero Mallah, consists of 55 households of the Mallah clan and the population of this village is around 500 people. Akram Mallah, 35 years old, is the only person in the entire village who is educated. He could barely pass Matriculation exams from Seerani High School, which is situated around 20 kilometres from this remote village. Nevertheless, Akram Mallah is their teacher, doctor, lawyer and generally the only source of information about the world outside for his fellow villagers.

The people of the village Kandero Mallah use to vote for the party of ‘Shaheeds’ (martyrs) for years. But until today, not a single elected representative has visited the village. Not a single member of a provincial or national assembly has tried to know more about the people of the village. Surprisingly, they don’t have any complain about anything from anyone. For them, Javed Khaskheli is a saviour because he intervened in this village through a nongovernmental organisation, the Hilal Ahmer Pakistan (Red Crescent). Javed Khaskheli not only supported them by imparting various trainings but also tried to provide direct material assistance – by providing sheep, goats and some other useful belongings for the deprived people of the village.

And so it happens that on a sweltering hot day in May, I along with Masood Lohar and Ameer Mandhro reach the village after traversing the barren lands of Roopa Marri. The deprivation, of course, is the first thing to strike me. I find myself thinking that the young women I see, 20 to 25 years old at most, look like much, much older women.

Looking at the local children, I observe something very odd. They don’t seem to be playing. The little girls have no concept of playing with dolls. The little boys have no notion of sports.

Hand pumps have stopped pumping fresh water. Rivers, ponds and other fresh water bodies have dried up. There is no concept of flowing water. It's hard to find a green piece of land in the entire region

I find myself wondering if the people of Kandero Mallah dare to dream.

But I do know for certain that this terrain of the ‘Larr’ region was once amongst the most eye-catching and fertile areas of Sindh. There would have been life, happiness and prosperity here – that, for me, is the only explanation for why the Soomra dynasty would make this place their capital of Sindh. Once upon a time, too, this region would have been a trading hub and conquerors like Alauddin Khilji attacked it in their greed, knowing that they would find much wealth.

But what wealth is to be found here right now?

Hand pumps have stopped pumping fresh water. Rivers, ponds and other fresh water bodies have dried up. There is no concept of flowing water. It’s hard to find a green piece of land in the entire region. The only tree left here in this part of the country is the “Devi” or Mesquite – which is a source of income for these people and fodder for their livestock. I do not know what meaning this tree has in the rest of the Indian Subcontinent, but for the people of Sindh’s coastal belt – including the villagers of Kandero Mallah – the tree has proved to be a true Devi (goddess) because they sell its wood and earn some money.

The people, nevertheless, if asked about their circumstances, always respond with “We are thankful to Almighty Allah that He shields us even in these harsh circumstances”. It makes me want to rethink my own priorities and view of life.

What they call their home is actually a number of straw huts which are mercilessly bathed by the sun’s heat. The scorching sunrays are observable even while sitting inside a hut. I’m not sure if there is a single place to breathe away from the raging heat in the entire village during summers.

Women carrying pitchers of water walk for several kilometres to get drinking water. They do not appear very concerned that elections are close at hand. They are also unconcerned about the changing of governments or the general circumstances of the country. Democracy and dictatorship are equally irrelevant for the villagers of Kandero Mallah. They don’t ask anyone for anything. Even the PPP’s catchphrase from the Bhutto era, “Roti, kapra aur makaan” (Bread, clothing and housing) means little to them. their grief into power.

The call to prayer reaches our ears. Masi Sakina stands up, leaves the conversation in the middle and informs me: “Son! It is Allah’s call, so I have to go to offer prayer.”

Incidentally, there is no mosque in this village – though there are many mosques and madrassahs built by religious organisations in the region more generally.

The 1999 cyclone brought devastation in southern Sindh – and in doing so, it changed the entire geography of the Larr region. This village also paid a heavy price during that calamity. The fisherfolk of the village, who were at sea on that day, haven’t come back till this day. No one knows what became of them. The people of the village also lost their livestock, huts and many other belongings in the cyclone. The fresh water which once used to reach in this region also stopped after that lethal cyclone.

I often think that if those ‘technical’ people who speak in favour of the Kalabagh Dam were to come and spend some hours in Kandero Mallah, their entire scientific philosophy and engineering might stop working.

I find myself thinking how unfair it is that in an era when Google Maps can be used to find the exact location of any place in the world, no app can mark the pain of the residents of village Kandero Mallah.

The writer is a freelancer based in Badin, Sindh. He can be reached at abbaskhaskheli110@gmail.com