Pakistan-Administered Kashmir, officially known as Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK), is all set to get more administrative and financial powers in the matters of its people. Though the nomenclature suggests that it is free, the all-powerful Kashmir Council headed by the Pakistani prime minister holds most of the crucial executive, legislative and financial powers. But a new wind of change is coming to the mountainous region as PM Shahid Khaqan Abbasi has given the go-ahead to abolish the Kashmir Council, paving the way for the empowerment of the region that is showcased as a symbol of the Jammu and Kashmir dispute.

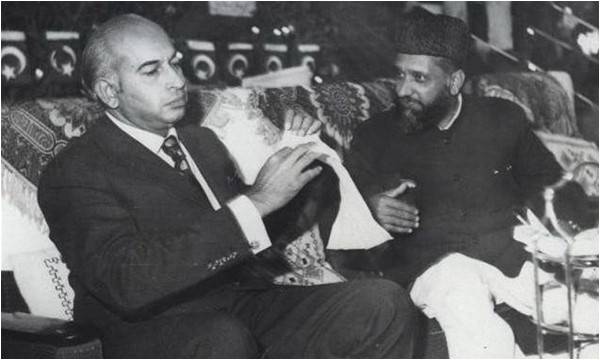

It has taken over four decades for the provisions to go after the then Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto brought them through the “Azad Jammu and Kashmir Interim Constitution of 1974”. Though not a complete comparison, “AJK’s” travesty in empowerment somehow mirrors that of Jammu and Kashmir as New Delhi has all along mauled it with different laws and by installing puppet regimes.

Till 1961 there was no proper mechanism to even elect leaders to govern the region. The foundation of relations between Islamabad and Muzaffarabad lie in the Karachi agreement of 1949 which limited it to defence, foreign policy, issuing currency and coinage, negotiations with the UNCIP, and coordination for the plebiscite and control of Gilgit-Baltistan.

But in the later years of 1950, 1952 and 1958, the rules of business were framed to further empower the local people. In 1961, the first presidential elections were held on a system of basic democracies, which was introduced by the then President Ayub Khan. Subsequently, two new Acts were introduced to push this “reform” to improve governance.

However, this changed with maverick Bhutto toppling the government of elected President Sardar Abdul Qayyum Khan, jailing him, conducting sham elections and installing his government of choice. What followed was a change in the constitution and a one-sided set-up called the Kashmir Council came into being. With six members elected by the “AJK” Assembly, five members are nominated by the PM of Pakistan from the Senate and National Assembly, with the Minister for Kashmir Affairs and Gilgit-Baltistan as an ex-officio member; the Prime Minister would himself be the chairman.

Virtually nothing was left for the Prime Minister of AJK and the Assembly to decide as the latter was barred from legislating on 52 subjects. Powers on important issues such as finances, taxes and even the Executive rested with the KC which ran a parallel government in Azad Kashmir. Tax collected from AJK would be arbitrarily spent by the KC and the appointment of judges and the election commission too would be made by the Council.

The struggle to restore the position has been a long one, and in fact, the current PM of AJK, Raja Farooq Haider Khan, has been one of the oldest advocates of disbanding the Council. In 2009, he was shown the door after he intensified efforts to challenge Islamabad’s supremacy. Local civil society groups managed a strong and constant pressure to do away with the Council.

The Centre for Peace, Development and Reforms, a think tank based in AJK/Islamabad launched a sustained campaign in 2010 and continued to generate awareness about it. “The Council enjoys unfettered jurisdiction and executive power over 52 subjects consequently hampering and impeding the elected government’s ability in decision making in key areas such as economic development, revenue generation, tourism, finance, public policy and socio-political development, hydropower generation, telecommunication etc. which runs contrary to the spirit and ideals of democratic norms & governance,” reads an online petition by the think tank which kick-started a discussion.

It is not known how the Abbasi government was convinced to agree to such a significant reform. But it comes after a committee headed by Planning Commission head Sartaj Aziz was tasked with reforms for Gilgit-Baltistan. Now the government has decided to disband both the council, the Kashmir Council and GB Council. In the case of the latter, however, Chief Minister Hafiz ur Rehman has reservations as he continues to enjoy provisional provincial status but is for withdrawing the powers from the Council.

The Gilgit-Baltistan Council is an independent legislative body headed by the prime minister of Pakistan and was established in May 2010 under Article 33 of GB (Empowerment and Self Governance) Order, 2010. The council has the mandate to legislate in 52 subjects. It was then President Asif Zardari who brought the drastic reform for GB in 2009 and changed the name from Northern Areas to GB besides setting up the elected bodies. A few years ago President Musharraf also introduced some reforms which enabled the region to elected assembly members and a Deputy Chief Executive to head the local administration. Former foreign secretary of India Shyam Saran interpreted it in a very interesting but in a larger context. He writes: Musharraf did initiate action to create elected bodies in Gilgit-Baltistan so that they could be represented in the proposed joint mechanism (between India and Pakistan over Jammu and Kashmir).

In the case of GB, the Pakistan government has a dilemma. It wants it to be a province but at the same time this conflicts with the demand for a final resolution to the state of Jammu and Kashmir under UN resolutions. This change of mind in Islamabad came in tune with the 18th Amendment of the Constitution of Pakistan that decentralised powers and empowered the provinces in 2010.

The decision by the Pakistan government is landmark one and it will not only address the simmering discontent in the region that had been consolidating diverse opinions, but it will also have an impact on a political resolution for the Jammu and Kashmir dispute. It is like restoring Jammu and Kashmir to its pre-1953 position when New Delhi enjoyed powers related to defence, communication and foreign affairs only. Gradually that was eroded, and Article 370 that gives special status to the state with the Indian constitution remains an empty shell. It remains to be seen whether Islamabad has played a political card vis-a-vis India to address “unrest” in the other part of Kashmir. But the fact is that this decision is of immense importance and will define a new relationship between Islamabad and Muzaffarabad though the rest remains unchanged as long as both countries wrangle over the “ownership” of the state.

It has taken over four decades for the provisions to go after the then Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto brought them through the “Azad Jammu and Kashmir Interim Constitution of 1974”. Though not a complete comparison, “AJK’s” travesty in empowerment somehow mirrors that of Jammu and Kashmir as New Delhi has all along mauled it with different laws and by installing puppet regimes.

Till 1961 there was no proper mechanism to even elect leaders to govern the region. The foundation of relations between Islamabad and Muzaffarabad lie in the Karachi agreement of 1949 which limited it to defence, foreign policy, issuing currency and coinage, negotiations with the UNCIP, and coordination for the plebiscite and control of Gilgit-Baltistan.

But in the later years of 1950, 1952 and 1958, the rules of business were framed to further empower the local people. In 1961, the first presidential elections were held on a system of basic democracies, which was introduced by the then President Ayub Khan. Subsequently, two new Acts were introduced to push this “reform” to improve governance.

The decision by the Pakistan government is landmark one. It will address simmering discontent in the region. It will have an impact on a resolution to the Jammu and Kashmir dispute

However, this changed with maverick Bhutto toppling the government of elected President Sardar Abdul Qayyum Khan, jailing him, conducting sham elections and installing his government of choice. What followed was a change in the constitution and a one-sided set-up called the Kashmir Council came into being. With six members elected by the “AJK” Assembly, five members are nominated by the PM of Pakistan from the Senate and National Assembly, with the Minister for Kashmir Affairs and Gilgit-Baltistan as an ex-officio member; the Prime Minister would himself be the chairman.

Virtually nothing was left for the Prime Minister of AJK and the Assembly to decide as the latter was barred from legislating on 52 subjects. Powers on important issues such as finances, taxes and even the Executive rested with the KC which ran a parallel government in Azad Kashmir. Tax collected from AJK would be arbitrarily spent by the KC and the appointment of judges and the election commission too would be made by the Council.

The struggle to restore the position has been a long one, and in fact, the current PM of AJK, Raja Farooq Haider Khan, has been one of the oldest advocates of disbanding the Council. In 2009, he was shown the door after he intensified efforts to challenge Islamabad’s supremacy. Local civil society groups managed a strong and constant pressure to do away with the Council.

The Centre for Peace, Development and Reforms, a think tank based in AJK/Islamabad launched a sustained campaign in 2010 and continued to generate awareness about it. “The Council enjoys unfettered jurisdiction and executive power over 52 subjects consequently hampering and impeding the elected government’s ability in decision making in key areas such as economic development, revenue generation, tourism, finance, public policy and socio-political development, hydropower generation, telecommunication etc. which runs contrary to the spirit and ideals of democratic norms & governance,” reads an online petition by the think tank which kick-started a discussion.

It is not known how the Abbasi government was convinced to agree to such a significant reform. But it comes after a committee headed by Planning Commission head Sartaj Aziz was tasked with reforms for Gilgit-Baltistan. Now the government has decided to disband both the council, the Kashmir Council and GB Council. In the case of the latter, however, Chief Minister Hafiz ur Rehman has reservations as he continues to enjoy provisional provincial status but is for withdrawing the powers from the Council.

The Gilgit-Baltistan Council is an independent legislative body headed by the prime minister of Pakistan and was established in May 2010 under Article 33 of GB (Empowerment and Self Governance) Order, 2010. The council has the mandate to legislate in 52 subjects. It was then President Asif Zardari who brought the drastic reform for GB in 2009 and changed the name from Northern Areas to GB besides setting up the elected bodies. A few years ago President Musharraf also introduced some reforms which enabled the region to elected assembly members and a Deputy Chief Executive to head the local administration. Former foreign secretary of India Shyam Saran interpreted it in a very interesting but in a larger context. He writes: Musharraf did initiate action to create elected bodies in Gilgit-Baltistan so that they could be represented in the proposed joint mechanism (between India and Pakistan over Jammu and Kashmir).

In the case of GB, the Pakistan government has a dilemma. It wants it to be a province but at the same time this conflicts with the demand for a final resolution to the state of Jammu and Kashmir under UN resolutions. This change of mind in Islamabad came in tune with the 18th Amendment of the Constitution of Pakistan that decentralised powers and empowered the provinces in 2010.

The decision by the Pakistan government is landmark one and it will not only address the simmering discontent in the region that had been consolidating diverse opinions, but it will also have an impact on a political resolution for the Jammu and Kashmir dispute. It is like restoring Jammu and Kashmir to its pre-1953 position when New Delhi enjoyed powers related to defence, communication and foreign affairs only. Gradually that was eroded, and Article 370 that gives special status to the state with the Indian constitution remains an empty shell. It remains to be seen whether Islamabad has played a political card vis-a-vis India to address “unrest” in the other part of Kashmir. But the fact is that this decision is of immense importance and will define a new relationship between Islamabad and Muzaffarabad though the rest remains unchanged as long as both countries wrangle over the “ownership” of the state.