I saw dawn upon them like the sun a vision

of a time when all men walk proudly through the earth

and the bombs and missiles lie at the bottom of the ocean

like the bones of dinosaurs buried under the shale of eras,

and men strive with each other not for power or theaccumulation of paper

but in joy create for others the house, the poem,

the gameof athletic beauty.

Then washed in the brightness of this vision,

I saw how in its radiance would grow and be nourished

and suddenly

burst into terrible and splendid bloom

the blood-red flower of revolution.

(African-American poet Dudley Randall)

The idea of Revolution is one that has generated enormous excitement through the centuries. This is despite the fact that many of the major Revolutions of the last century are seen to have been notable failures. The Russian Revolution of 1917 fathered the rigidly totalitarian Soviet police state which then collapsed and disintegrated in 1989. The Chinese Revolution of 1949 abandoned the utopian socialist dreams of its leaders and recast itself as the massive capitalist behemoth that it is today. The Iranian Revolution of 1979 transformed itself into a rigid theocracy and is stagnating.

Not a good track record, one might think. But none of these and other failures has served to deprive the idea of Revolution of its powerful romantic attraction. The concept evolved on the strength of the 17th-century British and the 18th-century American and French Revolutions. 19th-century Europe saw violent political upheavals accompanying the national unification processes of Germany, Italy and elsewhere. And the 20th century has seen a whole host of revolutionary eruptions around the world, including national liberation, anti-colonial, communist and professedly Islamic uprisings.

For Moore, the Subcontinent's people have shown an incredible tolerance of the intolerable through the millennia, down to today

I believe that one of the key points about the concept of Revolution is its “Red” iconography – the red of blood, the red of fire. It conjures the images of the blood from the laid-low tyrants and bosses of the corrupt “old order”.

“Sceptre and crown must tumble down

And in the dust be equal made

With the poor, crooked scythe and spade.”

(James Shirley)

Or it is the red of fire – the cleansing blaze that will consume the old tyranny and injustices and permit the new age of the world to emerge.

“The battle outside raging

Will soon shake your windows and rattle your halls.

For the times they are a-changing.”

(Bob Dylan)

Karl Marx saw political revolutions as an integral part of the process of socio-economic change, when the productive forces of a society have developed to a stage where they burst from the constraints of an existing political formation into the next, and higher, stage. He described the revolutions in Britain, America, and France as bourgeois revolutions, which freed the fledgling capitalist order from outdated feudal shackles and established modern constitutional democracy. Marx prognosticated eventual proletarian revolutions (uprisings of the working class), which would establish a socialist system and pave the way for a classless society.

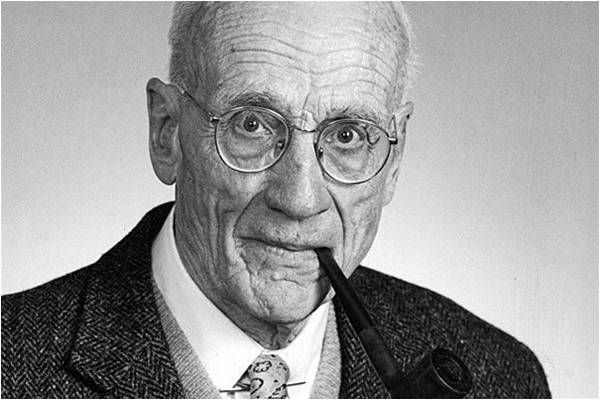

An analysis by American social historian Barrington Moore in his celebrated 1960s work Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy had several interesting features. Moore writes of three kinds of modernising revolutions that lifted societies out of feudal stagnation: The three capitalist revolutions, or “Revolutions from the middle”, in Britain, America, and France; the two socialist revolutions, or “Revolutions from below”, in Russia and China; and a third category, Fascist revolutions, or “Revolutions from above”, as in Bismarck’s Germany and Meiji Japan, where a coalition of elite groups ruthlessly transformed their societies from above. One or the other of these three kinds of revolution, in Moore’s view, was replicated in numerous other countries as they were transformed into differing states of modernity.

Moore also mentions a fourth category, a society that has not passed through a modernising revolution of any kind. The example he gives is that of our own Subcontinent, whose peoples, he feels, have shown an incredible level of tolerance of the intolerable through the millennia and down to today.

The cost in lives and human misery of revolutionary violence and the sacrifice of at least one generation to the post-revolutionary chaos is still less, in Moore’s view, than the unending low-level misery and continued poverty and exploitation of going without the kind of fundamental social and political transformations that only a revolution can bring about. He avers that the long-term cost of going without a revolution is far greater than the cost of revolution itself.

The thought is perhaps an uncomfortable one for liberals and social democrats (like the author himself), who have tended to think that the power of the ballot box is sufficient to drive out the demons of primitivism and exploitation without the need of recourse to revolutionary violence...with its unpredictability and spasms of irrationality. In Moore’s view (and Marx’s), a soil must be dyed the red of the perceived exploiters’ blood and of Prometheus’s heavenly fire before it can be cleansed.

The region that Moore is talking about is our own Subcontinent and includes us, as well as India and Bangladesh. I do not include little Nepal in this reckoning since, as we know, it is in fact undergoing the throes of a kind of revolution.

And are we? Is it conceivable that the violent Jihadi warriors, who are attacking again and again and damaging our state and society may be the vanguard of a coming revolution? Now, my reader must not get me wrong. I do not for a moment see people like Maulvi Fazlullah, or Ehsanullah Ehsan or Maulana Abdul Aziz as the vanguard of anything but their own nihilism. But is it not possible to see, in the bizarre kind of tacit acceptance that much of the public seems to have towards those like them, an indication of the unexpectedly deep well of anti-elitism and alienation that exists as a sub-conscious layer of darkness in our minds?

I do not want to dwell on this point, precisely because it is an uncomfortable one. I would, however, reiterate a view expressed elsewhere that we are riding on the cusp of a huge wave of history, as yet inchoate, and do not know where or how it will break.