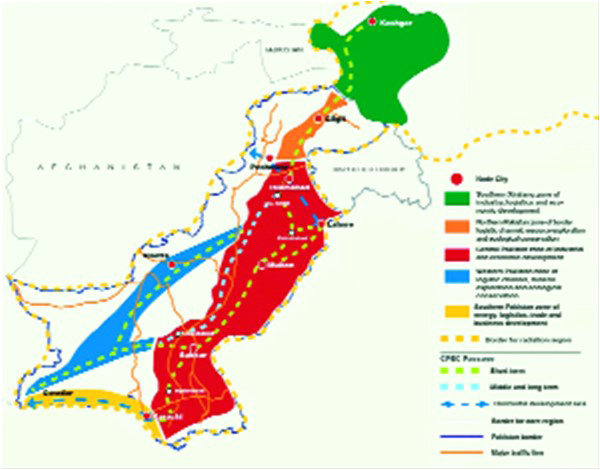

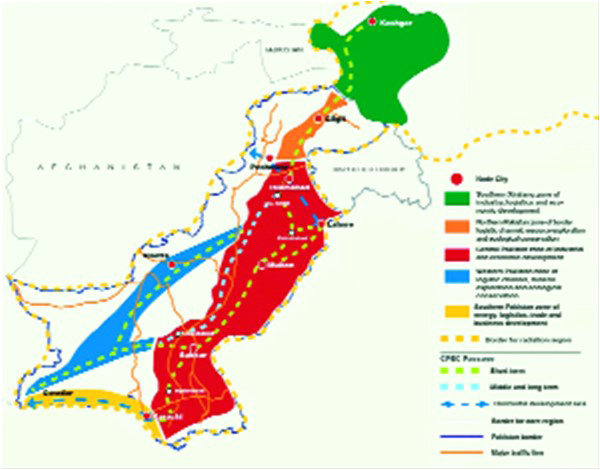

In 2013, China and Pakistan signed a Memorandum of Understanding that served as the cornerstone of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Two years later, Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Pakistan and formalized CPEC allocations at $46 billion. By the end of 2017, the total loans and investment under CPEC crossed $80 billion. Significantly, the early harvest projects have already started operating and scores of others with the port, in energy, railways, roads are currently underway.

To consolidate CPEC and bilateral economic cooperation, the Chinese and Pakistani governments concluded, at the sixth Joint Cooperation Council held in 2016, that they would set up Special Economic Zones. Initially, the total number varied from 46 to over a hundred. However, later on, the Pakistani authorities, in particular the Ministry of Planning, Development & Reform and the Board of Investment, reduced the number to nine, according to which each province, region (i.e. FATA) and the federal capital would host one.

For their part, the Chinese are also keen to deliberate on the concept and construction of industrial zones. Peking University held an academic seminar on this topic early this year. I attended it and the following observations are based on the paper presented and conversations held.

Benefits

Industrial zones could be a good economic opportunity for Pakistan but lessons can be learnt from the challenges that emerged when CPEC and special economic zones were discussed politically.

In 2015, when President Xi Jinping launched CPEC, the governments of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan and their political parties differed over CPEC ‘routes’. The so-called “route controversy” was blamed on the Punjab (and federal) government which were held partisan by the opposition political parties such as Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI) and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP).

Political parties based in non-Punjab provinces, especially Balochistan, that hosts Gwadar Port, raised questions on the feasibility, outreach, functions and strategic implications of CPEC. In the same vein, local politicians and rights activists from, for example, Gilgit-Baltistan highlighted the potential risks for the physical environment that would be potentially caused by CPEC traffic chains.

In order to address these grievances, the federal government led by PML-N held a series of meetings with key leaders of the provincial governments, regional dispensation and pro-climate change associations. It organized an all-parties conference on CPEC more than twice. Consequently, mainstream and regional political parties and groups, in general, and the federal and provincial governments, in particular, reached consensus on the nature and character of CPEC. Thus, the “route controversy” was amicably resolved with a due share of roads and railways allocated to different provinces and regions.

This exercise did not, however, entirely silence debate over the corridor. Most recently, Senator Mir Hasil Bizenjo, who is also the federal minister for ports and shipping, argued on the floor of the Senate that, “91% of the revenues to be generated from Gwadar port as part of CPEC would go to China, while the Gwadar Port Authority would get 9% share in the income for the next 40 years.”

In addition to this, the CPEC Long Term Plan invited concerns and questions from stakeholders and analysts alike. By and large, the political elite, especially from the smaller provinces, have demanded more transparency and fair play when it comes to details of the pros and cons of different agreements reached between the Chinese and Pakistani authorities. This means that though CPEC has been successfully accepted as a mega economic project between the two states, it still needs further buy-in at the popular level.

This signals that the construction of SEZs would not necessarily be free of political challenges emanating primarily from non-Punjab provinces and autonomous regions. There has already been considerable debate registered on the location, size and number of industrial zones by KP and Balochistan, if not Sindh, and nationalist political parties such as Pakhtunkhwa Milli Awami Party, the Awami National Party and the National Party. Small wonder then, that in initial meetings between the federal and provincial governments, the number of SEZs was reduced from over a hundred to forty-six and each government strove to host the maximum number of industrial zones which they felt would work on poverty, economic slowdown and unemployment on their turf. However, further negotiations brought the proposed number of SEZs down to nine according to which each province, the Islamabad Capital Territory and region would host one each.

This seems like a fair start in terms of equitable distribution numerically; however, issues and concerns on the size (the largest SEZ is proposed for Punjab) and economic competitiveness, the industrial base of a province/region and overall economic indicators of an area may pop up in the following months. As is the political culture, parties and politicians, tend to focus on their interests and that too at the expense of the larger interest. Thus, it is likely that SEZs will be further highlighted on partisan lines. Political disagreements and tussles, thus, amount to serious political challenges that demand serious and steady debate, negotiations and conflict resolution.

Political solutions

Long-term economic plans have often suffered from political instability. Therefore, in order to make CPEC a success story, Pakistani politicians and political parties have their work cut out.

Perhaps there is no harm in gradually increasing the equitable number and size of industrial zones in different parts of Pakistan. Such a policy would generate political confidence and economic collaboration among the four provinces, regions and the federal government.

More SEZs mean more local and regional participation in CPEC, economic growth and social progress. Moreover, the expansion of SEZs in partnership with local and provincial authorities is likely to assuage local and regional socioeconomic grievances by engaging local (semi-)skilled human resource of, for example, Gilgit-Baltistan and Balochistan.

The federal government should not ignore local and regional political aspirations. Mainstream political parties, which are major stakeholders of CPEC, ought not to sideline nationalist political parties of KP, Sindh and Balochistan. Thus, there is a need to develop an effective mechanism for inter-party coordination and policy formulation. At the moment, the federal government conducts an all-parties conference to discuss serious policy issues of national magnitude. This, in my view, is an ad hoc measure. A long-term institutional solution lies in the establishment of a permanent inter-party coordination body responsible for holding meetings, generating consensus on policy and, overall, ensuring participation of smaller political parties.

Security challenges

Pakistan is fighting religious extremism and terrorism. When the Pakistani military regime led by Pervez Musharraf (1999-2007) decided to support the US-led ‘war on terror’ against the Taliban and Al-Qaeda, the latter, in reaction, took on Pakistan by invoking (suicide) terrorism as a strategic weapon. Consequently, around thirty-thousand Pakistanis, both civilians and law enforcement members, have lost their lives in multiple attacks from 2003 till 2018. Though the number of civilian and security personnel fatalities has gone down comparatively since 2014 due largely to various military operations launched by the state of Pakistan, the phenomenon of terrorism has not been wiped out completely.

Given the opportunity, a terrorist organization such as Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and/or the Jamaat-ul-Ahrar (JuA) strikes mostly on the country’s minorities (Christians), in areas such as Quetta. A Chinese couple was kidnapped and killed in Quetta in 2017 by a terrorist organization.

Anti-Pakistan terrorist networks work in tandem with regional proxies and powers. For instance, it is no secret that Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi had spoken publicly against the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Given the domestic and regional security threats to its sovereignty, in general, and CPEC in particular, the Pakistani state has had to take measures that include pooling a special armed force, both civil and military, for the protection of CPEC projects and personnel. The latter consists of mostly Chinese citizens who number around 15,000.

9 special economic zones

1. Rashakai Economic Zone, M-1, Nowshera

2. China Special Economic Zone Dhabeji

3. Bostan Industrial Zone

4. Allama Iqbal Industrial City (M3), Faisalabad

5. ICT Model Industrial Zone, Islamabad

6. Industrial Park at Port Qasim near Karachi

7. Special Economic Zone at Mirpur, AJK

8. Mohmand Marble City

9. Moqpondass SEZ Gilgit-Baltistan

CPEC has, so far, not seen a major terrorist attack on its infrastructure and workforce. However, potential security threats should not be ignored. This raises security concerns for the proposed industrial zones. Will the local, provincial or federal government provide the SEZs security, at different stages of construction? If it is a joint venture of, for example, the provincial and federal governments, who will call the shots? Who will bear the financial and logistical costs? If it is the sole responsibility of the provincial government, will a province be able to manage an SEZ’s security on its own?

Overall, will the Chinese companies and workforce be satisfied with the security arrangements provided by the Pakistani authorities?

Security challenges

On December 8, 2017, the Chinese embassy in Islamabad issued a press release that read, “The Chinese embassy has received some information that the security of the Chinese institutions and personnel in Pakistan might be threatened. This Embassy would make it clear that Pakistan is a friendly country to China. We appreciate Pakistan has attached much importance to the security of the Chinese institutions and personnel.”

Why did the Chinese Embassy in Pakistan put a security alert on its website in the first place? Are the Chinese companies and labor working on CPEC really threatened in Pakistan? How is the general security situation in Pakistan and in what ways does it affect China-Pakistan relations?

China-Pakistan relations have achieved “a factor of durability”. Both countries amicably have been resolving potential areas of conflict generation i.e. broader management, and, have importantly, consolidated bilateral relations since the mid-1960s onwards. Consequently, since 2015, China-Pakistan relations have taken a new turn where geo-economics is predicated on geopolitics in terms of formalization of CPEC.

A considerable section of the Chinese workforce is engaged in Gwadar, where more than fifty major projects in infrastructure and energy are underway. The Pakistani authorities, being aware of the security situation, set up a security regime to safeguard the Chinese labor from mostly internal threats.

Though kidnappers in Balochistan killed two Chinese nationals this year, the overall safety of the Chinese workers has been ensured by the government of Pakistan. Moreover, lately there have been reports of some Chinese nationals having been involved in financial theft, i.e. ATM skimming fraud in Karachi, whose cases are being investigated. Nevertheless, the Chinese citizens working in Pakistan have overwhelmingly demonstrated goodwill and good conduct. At the moment, the majority of Pakistanis perceive them as friendly people from a friendly country. Nevertheless, given the chaotic security situation in parts of Pakistan, public safety remains a big challenge for law enforcement, which loses its police and military men to terrorism on almost a regular basis though with a reduction in the number of terror attacks.

In order to improve CPEC security, Pakistani authorities would have to tackle terrorism on multiple levels. Strategically, the country needs to engage with its neighbors meaningfully. Here, China can play a role by encouraging regional cooperation and peace. Indeed, the quadrilateral Afghan peace process is a step in the right direction. Moreover, China-Iran-Pakistan trilateral engagement carries the potential to devise a collective response to anti-peace elements in the South Asian region. Importantly, China may also convince the United States, another major stakeholder in the region, to engage Pakistan, Afghanistan and India in a manner that reduces strategic uncertainty.

Above all, China and Pakistan would have to play a central role by reinforcing the importance of peace and stability locally, nationally and trans-regionally. The former must understand the precarious security situation Pakistan is facing. It has lost more than 30,000 civilians and security personnel in past fifteen years. Pakistan must revisit its policies that might have provided an enabling environment to such forces.

The latter may have been militarily neutralized by the law enforcement, but certain militant organizations such as Jamaat-ul-Ahrar still pose a challenge. The JuA may activate its sleeper cells in major urban areas of KP, Karachi and Quetta. The JuA and similar organizations are always in search of soft targets.

Pakistan has to take certain extraordinary measures. One the one hand, there is need to devise a strategy to have local and provincial law enforcement apparatuses i.e. police, Frontier Constabulary, on board, enhance the policy and operational capacity of civil law enforcement, improve human intelligence of strategic locations along CPEC, including the proposed industrial zones. On the other hand, the local, provincial and federal governments ought to chalk out a policy framework under which the country’s armed law enforcement could work. Ideally, multiple institutions can perform optimally under a single but consolidated command structure. In this respect, the size of the already established CPEC Security Force could possibly be expanded.

Lastly, for effective surveillance of SEZs and Gwadar Port, the Chinese government can be helpful in terms of provision of sophisticated gadgets to enhance physical and infrastructural security of the enclave. Within the Gwadar enclave, the Chinese may, in consultation with Pakistani authorities, operate on its own. Nonetheless, handing the overall security of Gwadar and SEZs to Chinese companies, both public and private, would not be a feasible idea and option given Pakistan’s experiences. Since 9/11, China’s perception at the popular level is positive in Pakistan. The Chinese should stay mindful of this.

The author heads the department of Social Sciences at Iqra University Islamabad @ejazbhatty

To consolidate CPEC and bilateral economic cooperation, the Chinese and Pakistani governments concluded, at the sixth Joint Cooperation Council held in 2016, that they would set up Special Economic Zones. Initially, the total number varied from 46 to over a hundred. However, later on, the Pakistani authorities, in particular the Ministry of Planning, Development & Reform and the Board of Investment, reduced the number to nine, according to which each province, region (i.e. FATA) and the federal capital would host one.

For their part, the Chinese are also keen to deliberate on the concept and construction of industrial zones. Peking University held an academic seminar on this topic early this year. I attended it and the following observations are based on the paper presented and conversations held.

By and large, the political elite, especially from the smaller provinces, have demanded more transparency and fair play when it comes to details of the pros and cons of different agreements reached between the Chinese and Pakistani authorities

Benefits

Industrial zones could be a good economic opportunity for Pakistan but lessons can be learnt from the challenges that emerged when CPEC and special economic zones were discussed politically.

In 2015, when President Xi Jinping launched CPEC, the governments of Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan and their political parties differed over CPEC ‘routes’. The so-called “route controversy” was blamed on the Punjab (and federal) government which were held partisan by the opposition political parties such as Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaaf (PTI) and the Pakistan People’s Party (PPP).

Political parties based in non-Punjab provinces, especially Balochistan, that hosts Gwadar Port, raised questions on the feasibility, outreach, functions and strategic implications of CPEC. In the same vein, local politicians and rights activists from, for example, Gilgit-Baltistan highlighted the potential risks for the physical environment that would be potentially caused by CPEC traffic chains.

In order to address these grievances, the federal government led by PML-N held a series of meetings with key leaders of the provincial governments, regional dispensation and pro-climate change associations. It organized an all-parties conference on CPEC more than twice. Consequently, mainstream and regional political parties and groups, in general, and the federal and provincial governments, in particular, reached consensus on the nature and character of CPEC. Thus, the “route controversy” was amicably resolved with a due share of roads and railways allocated to different provinces and regions.

This exercise did not, however, entirely silence debate over the corridor. Most recently, Senator Mir Hasil Bizenjo, who is also the federal minister for ports and shipping, argued on the floor of the Senate that, “91% of the revenues to be generated from Gwadar port as part of CPEC would go to China, while the Gwadar Port Authority would get 9% share in the income for the next 40 years.”

In addition to this, the CPEC Long Term Plan invited concerns and questions from stakeholders and analysts alike. By and large, the political elite, especially from the smaller provinces, have demanded more transparency and fair play when it comes to details of the pros and cons of different agreements reached between the Chinese and Pakistani authorities. This means that though CPEC has been successfully accepted as a mega economic project between the two states, it still needs further buy-in at the popular level.

This signals that the construction of SEZs would not necessarily be free of political challenges emanating primarily from non-Punjab provinces and autonomous regions. There has already been considerable debate registered on the location, size and number of industrial zones by KP and Balochistan, if not Sindh, and nationalist political parties such as Pakhtunkhwa Milli Awami Party, the Awami National Party and the National Party. Small wonder then, that in initial meetings between the federal and provincial governments, the number of SEZs was reduced from over a hundred to forty-six and each government strove to host the maximum number of industrial zones which they felt would work on poverty, economic slowdown and unemployment on their turf. However, further negotiations brought the proposed number of SEZs down to nine according to which each province, the Islamabad Capital Territory and region would host one each.

This seems like a fair start in terms of equitable distribution numerically; however, issues and concerns on the size (the largest SEZ is proposed for Punjab) and economic competitiveness, the industrial base of a province/region and overall economic indicators of an area may pop up in the following months. As is the political culture, parties and politicians, tend to focus on their interests and that too at the expense of the larger interest. Thus, it is likely that SEZs will be further highlighted on partisan lines. Political disagreements and tussles, thus, amount to serious political challenges that demand serious and steady debate, negotiations and conflict resolution.

Initially, the total number of SEZs varied from 46 to over a hundred. However, later on, the Pakistani authorities, in particular the Ministry of Planning, Development & Reform and the Board of Investment, reduced the number to nine, according to which each province, region (i.e. FATA) and the federal capital would host one

Political solutions

Long-term economic plans have often suffered from political instability. Therefore, in order to make CPEC a success story, Pakistani politicians and political parties have their work cut out.

Perhaps there is no harm in gradually increasing the equitable number and size of industrial zones in different parts of Pakistan. Such a policy would generate political confidence and economic collaboration among the four provinces, regions and the federal government.

More SEZs mean more local and regional participation in CPEC, economic growth and social progress. Moreover, the expansion of SEZs in partnership with local and provincial authorities is likely to assuage local and regional socioeconomic grievances by engaging local (semi-)skilled human resource of, for example, Gilgit-Baltistan and Balochistan.

The federal government should not ignore local and regional political aspirations. Mainstream political parties, which are major stakeholders of CPEC, ought not to sideline nationalist political parties of KP, Sindh and Balochistan. Thus, there is a need to develop an effective mechanism for inter-party coordination and policy formulation. At the moment, the federal government conducts an all-parties conference to discuss serious policy issues of national magnitude. This, in my view, is an ad hoc measure. A long-term institutional solution lies in the establishment of a permanent inter-party coordination body responsible for holding meetings, generating consensus on policy and, overall, ensuring participation of smaller political parties.

Security challenges

Pakistan is fighting religious extremism and terrorism. When the Pakistani military regime led by Pervez Musharraf (1999-2007) decided to support the US-led ‘war on terror’ against the Taliban and Al-Qaeda, the latter, in reaction, took on Pakistan by invoking (suicide) terrorism as a strategic weapon. Consequently, around thirty-thousand Pakistanis, both civilians and law enforcement members, have lost their lives in multiple attacks from 2003 till 2018. Though the number of civilian and security personnel fatalities has gone down comparatively since 2014 due largely to various military operations launched by the state of Pakistan, the phenomenon of terrorism has not been wiped out completely.

Given the opportunity, a terrorist organization such as Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) and/or the Jamaat-ul-Ahrar (JuA) strikes mostly on the country’s minorities (Christians), in areas such as Quetta. A Chinese couple was kidnapped and killed in Quetta in 2017 by a terrorist organization.

Anti-Pakistan terrorist networks work in tandem with regional proxies and powers. For instance, it is no secret that Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi had spoken publicly against the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Given the domestic and regional security threats to its sovereignty, in general, and CPEC in particular, the Pakistani state has had to take measures that include pooling a special armed force, both civil and military, for the protection of CPEC projects and personnel. The latter consists of mostly Chinese citizens who number around 15,000.

9 special economic zones

1. Rashakai Economic Zone, M-1, Nowshera

2. China Special Economic Zone Dhabeji

3. Bostan Industrial Zone

4. Allama Iqbal Industrial City (M3), Faisalabad

5. ICT Model Industrial Zone, Islamabad

6. Industrial Park at Port Qasim near Karachi

7. Special Economic Zone at Mirpur, AJK

8. Mohmand Marble City

9. Moqpondass SEZ Gilgit-Baltistan

CPEC has, so far, not seen a major terrorist attack on its infrastructure and workforce. However, potential security threats should not be ignored. This raises security concerns for the proposed industrial zones. Will the local, provincial or federal government provide the SEZs security, at different stages of construction? If it is a joint venture of, for example, the provincial and federal governments, who will call the shots? Who will bear the financial and logistical costs? If it is the sole responsibility of the provincial government, will a province be able to manage an SEZ’s security on its own?

Overall, will the Chinese companies and workforce be satisfied with the security arrangements provided by the Pakistani authorities?

Security challenges

On December 8, 2017, the Chinese embassy in Islamabad issued a press release that read, “The Chinese embassy has received some information that the security of the Chinese institutions and personnel in Pakistan might be threatened. This Embassy would make it clear that Pakistan is a friendly country to China. We appreciate Pakistan has attached much importance to the security of the Chinese institutions and personnel.”

Why did the Chinese Embassy in Pakistan put a security alert on its website in the first place? Are the Chinese companies and labor working on CPEC really threatened in Pakistan? How is the general security situation in Pakistan and in what ways does it affect China-Pakistan relations?

China-Pakistan relations have achieved “a factor of durability”. Both countries amicably have been resolving potential areas of conflict generation i.e. broader management, and, have importantly, consolidated bilateral relations since the mid-1960s onwards. Consequently, since 2015, China-Pakistan relations have taken a new turn where geo-economics is predicated on geopolitics in terms of formalization of CPEC.

A considerable section of the Chinese workforce is engaged in Gwadar, where more than fifty major projects in infrastructure and energy are underway. The Pakistani authorities, being aware of the security situation, set up a security regime to safeguard the Chinese labor from mostly internal threats.

Though kidnappers in Balochistan killed two Chinese nationals this year, the overall safety of the Chinese workers has been ensured by the government of Pakistan. Moreover, lately there have been reports of some Chinese nationals having been involved in financial theft, i.e. ATM skimming fraud in Karachi, whose cases are being investigated. Nevertheless, the Chinese citizens working in Pakistan have overwhelmingly demonstrated goodwill and good conduct. At the moment, the majority of Pakistanis perceive them as friendly people from a friendly country. Nevertheless, given the chaotic security situation in parts of Pakistan, public safety remains a big challenge for law enforcement, which loses its police and military men to terrorism on almost a regular basis though with a reduction in the number of terror attacks.

In order to improve CPEC security, Pakistani authorities would have to tackle terrorism on multiple levels. Strategically, the country needs to engage with its neighbors meaningfully. Here, China can play a role by encouraging regional cooperation and peace. Indeed, the quadrilateral Afghan peace process is a step in the right direction. Moreover, China-Iran-Pakistan trilateral engagement carries the potential to devise a collective response to anti-peace elements in the South Asian region. Importantly, China may also convince the United States, another major stakeholder in the region, to engage Pakistan, Afghanistan and India in a manner that reduces strategic uncertainty.

Above all, China and Pakistan would have to play a central role by reinforcing the importance of peace and stability locally, nationally and trans-regionally. The former must understand the precarious security situation Pakistan is facing. It has lost more than 30,000 civilians and security personnel in past fifteen years. Pakistan must revisit its policies that might have provided an enabling environment to such forces.

The latter may have been militarily neutralized by the law enforcement, but certain militant organizations such as Jamaat-ul-Ahrar still pose a challenge. The JuA may activate its sleeper cells in major urban areas of KP, Karachi and Quetta. The JuA and similar organizations are always in search of soft targets.

Pakistan has to take certain extraordinary measures. One the one hand, there is need to devise a strategy to have local and provincial law enforcement apparatuses i.e. police, Frontier Constabulary, on board, enhance the policy and operational capacity of civil law enforcement, improve human intelligence of strategic locations along CPEC, including the proposed industrial zones. On the other hand, the local, provincial and federal governments ought to chalk out a policy framework under which the country’s armed law enforcement could work. Ideally, multiple institutions can perform optimally under a single but consolidated command structure. In this respect, the size of the already established CPEC Security Force could possibly be expanded.

Lastly, for effective surveillance of SEZs and Gwadar Port, the Chinese government can be helpful in terms of provision of sophisticated gadgets to enhance physical and infrastructural security of the enclave. Within the Gwadar enclave, the Chinese may, in consultation with Pakistani authorities, operate on its own. Nonetheless, handing the overall security of Gwadar and SEZs to Chinese companies, both public and private, would not be a feasible idea and option given Pakistan’s experiences. Since 9/11, China’s perception at the popular level is positive in Pakistan. The Chinese should stay mindful of this.

The author heads the department of Social Sciences at Iqra University Islamabad @ejazbhatty