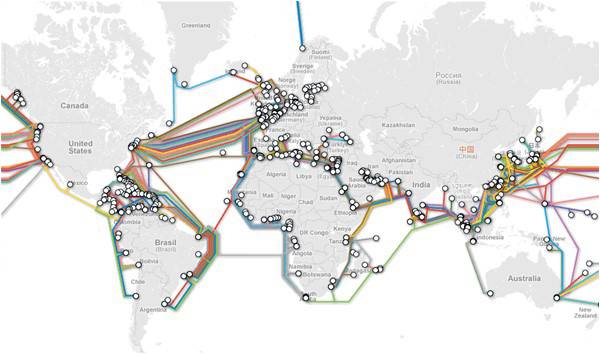

On August 5, IMEWE, one of six international underwater cables responsible for bringing internet to Pakistan, was cut near Jeddah. With SEAMEWE 4 and TW1 already offline due to technical issues, the internet went down throughout the country.

Two digital media officials from leading media houses, whose websites are in the Top 50 for Alexa ranking in Pakistan, confirmed that they experienced a traffic shortfall of 25% and 35%, respectively.

“The traffic figures we posted on Saturday and the first half of Sunday were some of the lowest in years,” said a social media executive of one of the websites. “Considering how hot the political scene is these days, the plummet was even more anomalous.”

Pakistan Telecommunication Company Limited (PTCL), that regulates IMEWE and SEAMEWE 4, along with SEAMEWE 3—with the rest managed by Transworld Associates (TWA)—experienced choked bandwidth. “We require an NoC from the Ministry of Defence to allow work on any underwater cable,” said a PTCL official. “It took us a month to get that for the cable that had been broken for a while.”

According to experts, cables can routinely develop faults. “There are land cables, sea cables and there are satellite links as well. It’s normal for there to be cuts in the cables,” said Khurram Ali Mehran, the PR director at the regulatory Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA). “The traffic is then rerouted elsewhere, which takes time.”

Mavra Khokhar, a telecommunication engineer, says it is criminal negligence not to have a backup plan in case a cable goes offline in this day and age. “There should be a consortium for all the cables with percentage shares determined,” she said. “The agreement should allow for there to be an increase of the percentage share in the overall cable capacity in case of an emergency.”

According to Mehran, there are agreements in place, both with international carriers and local infrastructure as well, and the PTA is encouraging PTCL and TWA to sign agreements that would allow both carriers to help each other out in case of an emergency. The PTA had advised both carriers to work out the plan in December 2016 when fiber optic cables were cut between Sindh and Balochistan, in four places including Hub and Khuzdar, and Karachi’s Gulshan-e-Hadeed and Nooriabad.

A TWA official confirmed that as soon as the PTCL cable went down over the weekend, they had offered backup support. “We offered to arrange it for around $30,000, which isn’t that big an amount. They took 8 hours to decide. By that time the cable in Jeddah was fixed as well.” However, the PTCL official says the company has approval procedures, which cannot be circumvented unless there is an agreement to finalise the protocol in such cases in the future.

With IMEWE, SEAMEWE 4 and TW1 offline, most of the data burden fell on the newly inaugurated 25,000km AAE-1, which started working July 2. “Such alternatives are critical. Government organisations and the Armed forces do not lose their connections, because they already have backup from TWA,” the TWA official said. “That’s the sort of mechanism that we need to devise for the rest of the country as well.”

Khurram Ali Mehran reiterates that work is already in progress. “There was a time when Pakistan only had one cable coming, now there are alternatives available. There is another cable coming from China to Rawalpindi.” The $44 million Pakistan-China Optical Fiber Cable Project, a part of CPEC, which includes an 820km long cable between Rawalpindi and Khunjrab will be inaugurated in two years.

Much like other projects affiliated with the corridor, the overarching influence of Beijing is generating concern among rights groups. “Knowing China’s track record on surveillance and tight control over the internet through censorship, it is imperative that the Pakistani government makes transparent the terms of reference of this new proposed cable via China,” says Usama Khilji, director of Bolo Bhi.

“Nevertheless, this poses a further threat to internet freedom in Pakistan, especially after the introduction of the draconian PECA 16 (cybercrime law) that we see is being used to silence political dissent apart from its necessary use for punishing harassment over the Internet.”

However, Khurram Ali Mehran says linking a technical question to freedom of expression is ‘bizarre’.

“China’s help in constructing the optical fibre cable is like a building a pipe that allows the flow of water – or a gas pipeline if you will,” he says. “What you do with the gas or water is your business.”

Two digital media officials from leading media houses, whose websites are in the Top 50 for Alexa ranking in Pakistan, confirmed that they experienced a traffic shortfall of 25% and 35%, respectively.

“The traffic figures we posted on Saturday and the first half of Sunday were some of the lowest in years,” said a social media executive of one of the websites. “Considering how hot the political scene is these days, the plummet was even more anomalous.”

"We require an NoC from the Ministry of Defence to allow work on any underwater cable," said a PTCL official. "It took us a month to get that for the cable that had been broken for a while"

Pakistan Telecommunication Company Limited (PTCL), that regulates IMEWE and SEAMEWE 4, along with SEAMEWE 3—with the rest managed by Transworld Associates (TWA)—experienced choked bandwidth. “We require an NoC from the Ministry of Defence to allow work on any underwater cable,” said a PTCL official. “It took us a month to get that for the cable that had been broken for a while.”

According to experts, cables can routinely develop faults. “There are land cables, sea cables and there are satellite links as well. It’s normal for there to be cuts in the cables,” said Khurram Ali Mehran, the PR director at the regulatory Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA). “The traffic is then rerouted elsewhere, which takes time.”

Mavra Khokhar, a telecommunication engineer, says it is criminal negligence not to have a backup plan in case a cable goes offline in this day and age. “There should be a consortium for all the cables with percentage shares determined,” she said. “The agreement should allow for there to be an increase of the percentage share in the overall cable capacity in case of an emergency.”

According to Mehran, there are agreements in place, both with international carriers and local infrastructure as well, and the PTA is encouraging PTCL and TWA to sign agreements that would allow both carriers to help each other out in case of an emergency. The PTA had advised both carriers to work out the plan in December 2016 when fiber optic cables were cut between Sindh and Balochistan, in four places including Hub and Khuzdar, and Karachi’s Gulshan-e-Hadeed and Nooriabad.

A TWA official confirmed that as soon as the PTCL cable went down over the weekend, they had offered backup support. “We offered to arrange it for around $30,000, which isn’t that big an amount. They took 8 hours to decide. By that time the cable in Jeddah was fixed as well.” However, the PTCL official says the company has approval procedures, which cannot be circumvented unless there is an agreement to finalise the protocol in such cases in the future.

With IMEWE, SEAMEWE 4 and TW1 offline, most of the data burden fell on the newly inaugurated 25,000km AAE-1, which started working July 2. “Such alternatives are critical. Government organisations and the Armed forces do not lose their connections, because they already have backup from TWA,” the TWA official said. “That’s the sort of mechanism that we need to devise for the rest of the country as well.”

Khurram Ali Mehran reiterates that work is already in progress. “There was a time when Pakistan only had one cable coming, now there are alternatives available. There is another cable coming from China to Rawalpindi.” The $44 million Pakistan-China Optical Fiber Cable Project, a part of CPEC, which includes an 820km long cable between Rawalpindi and Khunjrab will be inaugurated in two years.

Much like other projects affiliated with the corridor, the overarching influence of Beijing is generating concern among rights groups. “Knowing China’s track record on surveillance and tight control over the internet through censorship, it is imperative that the Pakistani government makes transparent the terms of reference of this new proposed cable via China,” says Usama Khilji, director of Bolo Bhi.

“Nevertheless, this poses a further threat to internet freedom in Pakistan, especially after the introduction of the draconian PECA 16 (cybercrime law) that we see is being used to silence political dissent apart from its necessary use for punishing harassment over the Internet.”

However, Khurram Ali Mehran says linking a technical question to freedom of expression is ‘bizarre’.

“China’s help in constructing the optical fibre cable is like a building a pipe that allows the flow of water – or a gas pipeline if you will,” he says. “What you do with the gas or water is your business.”