Afghan Taliban have stepped up attacks across Afghanistan, perpetuating the prevailing sense of insecurity there even as the Trump administration struggles to finalize its strategy for dealing with the sixteen-year-old war aimed at breaking the stalemate in the protracted conflict.

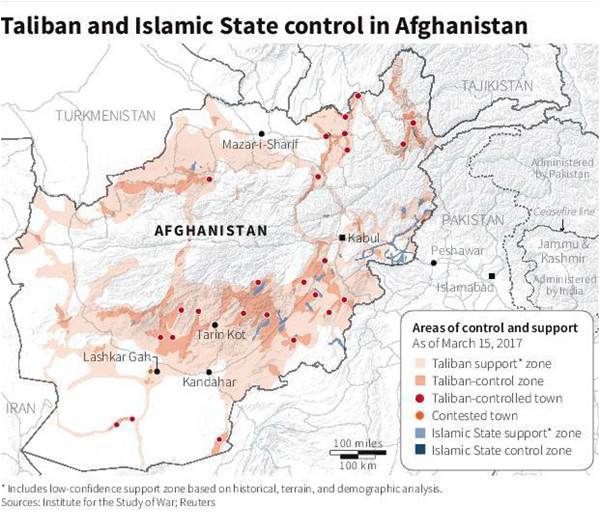

The Taliban earlier this week claimed a bomb attack in Kabul in which some 26 people lost their lives. The bombing took place as the group’s fighters seized control of three districts – Kohistan in northern Faryab province, Taiwara in Ghor province in central Afghanistan towards north-west, and Jani Khel in Paktia Province in the east of the country – from Afghan security forces that now have control over about 57% of territory. The rest is either controlled or contested by the Taliban, whereas Da’ish has occupied some parts as well.

Intense fighting between Taliban and Afghan security forces is, meanwhile, continuing in at least nine provinces in the north, north-east and south of Afghanistan. Some of the provinces where major clashes are taking place include Balkh, Baghlan, Badakhshan, Kunduz, Helmand, Kandahar, and Uruzgan. Da’ish is also expanding its footprint mostly in areas bordering Pakistan.

Summers have always been bad for Afghanistan ever since the insurgency began because it’s the time that the Taliban’s spring offensive, lush with finances from an opium crop, is in its full momentum, but this year has particularly looked to be much worse with the Taliban resorting to more attacks in populated settlements because of which the number of civilians being killed, particularly women and children, has risen. As per UN statistics, there have been 1,662 civilian deaths during the first six months of the year, a majority of which was because of suicide attacks and improvised explosive device blasts. About 19% of these casualties were from Kabul, which bore the brunt of these attacks.

Military casualties have also been shockingly high.

“The level of violence this year looks unprecedented,” Afghan political analyst Eshaq Amiri said in a telephonic conversation from Kabul. “Taliban terrorists are maintaining their momentum in the ground fighting and keeping security forces under pressure,” he said, noting intensified attacks in urban areas were meant to draw more media attention and add to growing dissatisfaction about the performance of the government especially with respect to security.

The most scathing criticism of the government’s failure to deal with the Taliban insurgency came from Hizb-e-Islami Chief Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, who returned to Kabul in May this year after striking a peace deal with the Afghan government. He said: “The (Ghani) government is not even able to properly ensure the safety of the Presidential Palace.”

Several reasons are being attributed to the spike in violence in Afghanistan.

Pakistan is the most convenient scapegoat. It has always been blamed for not doing enough to eliminate the Taliban and Haqqani Network’s alleged sanctuaries on its soil – something, which was also reiterated in the State Department’s Country Reports on Terrorism released last week. Pakistan also lost $50 million in Coalition Support Fund reimbursements this year for the same reason after Defense Secretary Mattis refused to certify that Pakistan had taken action against the two groups.

Meanwhile, Afghan Defense Ministry Spokesman Dawlat Waziri blames Pakistan for pushing Taliban fighters into Afghanistan without neutralizing them. Pakistan has always denied this charge and FO Spokesman Nafees Zakaria points towards the killing of key terrorist commanders on Afghan soil as proof that they were in Afghanistan and not in Pakistan.

But, the issue is much more complicated than that.

The Trump administration’s indecision and lack of clarity on how to deal with Taliban and Da’ish problems is breeding uncertainty. This suits the militants, who through increased activity are trying to give an impression that they have an upper hand in the conflict. They need to be denied this advantage.

The situation is exacerbated by the internal political conflicts that have embroiled the Ghani-Abdullah government. The rifts are adding to dysfunction of the government and distracting it from the fight against terrorists. The government’s failure to complete the cabinet and fill Supreme Court vacancies is just one indication of its dysfunction.

Afghan political analysts fear that the existing political set-up may collapse if the political wrangling does not end, which would be a scary scenario and could allow Taliban and Da’ish to gain control of more territory.

Pervasive corruption, and political and ethnic biases, besides creating political issues, are promoting a culture of impunity in Afghanistan, where officials quite often escape accountability for their lapses and wrongdoings simply because of their affiliations and connections.

According to Brookings’ Vanda Felbab-Brown: “Extensive predatory criminality, corruption, and power abuse—not effectively countered by the Afghan government—have facilitated the Taliban’s entrenchment.”

The Taliban have also suffered from internal divisions, but the perception of a “common enemy” has helped them to remain together. Reports of Taliban leader Maulvi Haibatullah’s son Hafiz Abdul Rehman Khalid carrying out a suicide attack has motivated and encouraged their ranks even though it sets the deadly precedent of endorsing such gruesome acts.

The impact of instability and violence in Afghanistan is not just restricted to the war-ravaged country. Its neighbours, Pakistan in particular, suffer from it. The continuing conflict has provided safe haven to terrorist groups there, who have attacked Pakistan. Ferozepur Road (Lahore) attack this week is a reminder of this reality.

Army Chief Gen Qamar Bajwa pointed to this while visiting Lahore after the attack when he offered Afghanistan help in clearing the border areas, where TTP, Jamaat-ul-Ahrar and other Pakistani terrorist groups have established sanctuaries.

At the same time the bilateral distrust by Taliban violence prevents any opportunity of cooperation between the two neighbours against terrorism. The disconnect pushes Afghanistan deeper into India’s embrace.

The writer is a freelance journalist based in Islamabad and tweets at @bokhari_mr

The Taliban earlier this week claimed a bomb attack in Kabul in which some 26 people lost their lives. The bombing took place as the group’s fighters seized control of three districts – Kohistan in northern Faryab province, Taiwara in Ghor province in central Afghanistan towards north-west, and Jani Khel in Paktia Province in the east of the country – from Afghan security forces that now have control over about 57% of territory. The rest is either controlled or contested by the Taliban, whereas Da’ish has occupied some parts as well.

Intense fighting between Taliban and Afghan security forces is, meanwhile, continuing in at least nine provinces in the north, north-east and south of Afghanistan. Some of the provinces where major clashes are taking place include Balkh, Baghlan, Badakhshan, Kunduz, Helmand, Kandahar, and Uruzgan. Da’ish is also expanding its footprint mostly in areas bordering Pakistan.

The Trump administration's indecision and lack of clarity on how to deal with Taliban and Da'ish problems is breeding uncertainty. This suits the militants, who through increased activity are trying to give an impression that they have an upper hand in the conflict. They need to be denied this advantage

Summers have always been bad for Afghanistan ever since the insurgency began because it’s the time that the Taliban’s spring offensive, lush with finances from an opium crop, is in its full momentum, but this year has particularly looked to be much worse with the Taliban resorting to more attacks in populated settlements because of which the number of civilians being killed, particularly women and children, has risen. As per UN statistics, there have been 1,662 civilian deaths during the first six months of the year, a majority of which was because of suicide attacks and improvised explosive device blasts. About 19% of these casualties were from Kabul, which bore the brunt of these attacks.

Military casualties have also been shockingly high.

“The level of violence this year looks unprecedented,” Afghan political analyst Eshaq Amiri said in a telephonic conversation from Kabul. “Taliban terrorists are maintaining their momentum in the ground fighting and keeping security forces under pressure,” he said, noting intensified attacks in urban areas were meant to draw more media attention and add to growing dissatisfaction about the performance of the government especially with respect to security.

The most scathing criticism of the government’s failure to deal with the Taliban insurgency came from Hizb-e-Islami Chief Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, who returned to Kabul in May this year after striking a peace deal with the Afghan government. He said: “The (Ghani) government is not even able to properly ensure the safety of the Presidential Palace.”

Several reasons are being attributed to the spike in violence in Afghanistan.

Pakistan is the most convenient scapegoat. It has always been blamed for not doing enough to eliminate the Taliban and Haqqani Network’s alleged sanctuaries on its soil – something, which was also reiterated in the State Department’s Country Reports on Terrorism released last week. Pakistan also lost $50 million in Coalition Support Fund reimbursements this year for the same reason after Defense Secretary Mattis refused to certify that Pakistan had taken action against the two groups.

Meanwhile, Afghan Defense Ministry Spokesman Dawlat Waziri blames Pakistan for pushing Taliban fighters into Afghanistan without neutralizing them. Pakistan has always denied this charge and FO Spokesman Nafees Zakaria points towards the killing of key terrorist commanders on Afghan soil as proof that they were in Afghanistan and not in Pakistan.

But, the issue is much more complicated than that.

The Trump administration’s indecision and lack of clarity on how to deal with Taliban and Da’ish problems is breeding uncertainty. This suits the militants, who through increased activity are trying to give an impression that they have an upper hand in the conflict. They need to be denied this advantage.

The situation is exacerbated by the internal political conflicts that have embroiled the Ghani-Abdullah government. The rifts are adding to dysfunction of the government and distracting it from the fight against terrorists. The government’s failure to complete the cabinet and fill Supreme Court vacancies is just one indication of its dysfunction.

Afghan political analysts fear that the existing political set-up may collapse if the political wrangling does not end, which would be a scary scenario and could allow Taliban and Da’ish to gain control of more territory.

Pervasive corruption, and political and ethnic biases, besides creating political issues, are promoting a culture of impunity in Afghanistan, where officials quite often escape accountability for their lapses and wrongdoings simply because of their affiliations and connections.

According to Brookings’ Vanda Felbab-Brown: “Extensive predatory criminality, corruption, and power abuse—not effectively countered by the Afghan government—have facilitated the Taliban’s entrenchment.”

The Taliban have also suffered from internal divisions, but the perception of a “common enemy” has helped them to remain together. Reports of Taliban leader Maulvi Haibatullah’s son Hafiz Abdul Rehman Khalid carrying out a suicide attack has motivated and encouraged their ranks even though it sets the deadly precedent of endorsing such gruesome acts.

The impact of instability and violence in Afghanistan is not just restricted to the war-ravaged country. Its neighbours, Pakistan in particular, suffer from it. The continuing conflict has provided safe haven to terrorist groups there, who have attacked Pakistan. Ferozepur Road (Lahore) attack this week is a reminder of this reality.

Army Chief Gen Qamar Bajwa pointed to this while visiting Lahore after the attack when he offered Afghanistan help in clearing the border areas, where TTP, Jamaat-ul-Ahrar and other Pakistani terrorist groups have established sanctuaries.

At the same time the bilateral distrust by Taliban violence prevents any opportunity of cooperation between the two neighbours against terrorism. The disconnect pushes Afghanistan deeper into India’s embrace.

The writer is a freelance journalist based in Islamabad and tweets at @bokhari_mr