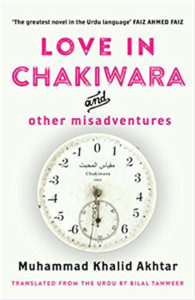

The author’s preface to Love In Chakiwara is a letter that Muhammad Khalid Akhtar wrote to his friend – who he charmingly addresses as Signor Riyazeno – in which he talks about what inspired him to write this book. He wished to capture life in Chakiwara in ‘Stevenson’s colours’ (he only mentions that this was his aim and does not waste time explaining how he has managed to do this). The town of Chakiwara is where he claims to have spent ‘one or two bohemian years’ of his life. In many ways the preface is written similarly to the stories in this collection. The writer remembers days that have long passed, makes fun of himself, recounts a story (on Manto in his sickbed) and then says he has no choice but to end the letter abruptly as his publisher has allowed him just two sheets for the preface. Much like Qurban Ali Kattar, the lovelorn novelist of Chakiwara, Muhammad Khalid Akhtar is also restrained by the practicalities of the real world but he acknowledges this with good humour.

The author’s preface to Love In Chakiwara is a letter that Muhammad Khalid Akhtar wrote to his friend – who he charmingly addresses as Signor Riyazeno – in which he talks about what inspired him to write this book. He wished to capture life in Chakiwara in ‘Stevenson’s colours’ (he only mentions that this was his aim and does not waste time explaining how he has managed to do this). The town of Chakiwara is where he claims to have spent ‘one or two bohemian years’ of his life. In many ways the preface is written similarly to the stories in this collection. The writer remembers days that have long passed, makes fun of himself, recounts a story (on Manto in his sickbed) and then says he has no choice but to end the letter abruptly as his publisher has allowed him just two sheets for the preface. Much like Qurban Ali Kattar, the lovelorn novelist of Chakiwara, Muhammad Khalid Akhtar is also restrained by the practicalities of the real world but he acknowledges this with good humour.We have been told, in the preface, that the real character of the novel is Chakiwara and that the characters are secondary but it is difficult not to be distracted by the host of characters Khalid Akhtar has created. He claims there is a certain Wodehousian vitality about them but these characters are in fact much more entertaining. There is Iqbal Changezi, owner of Allah Tawakkul Bakery and collector of washed-up writers; Ah Fung, the dentist with a shadowy past; Dr. Ghareeb Muhammad, inventor of the love meter; Qurban Ali Kattar, the ‘Thomas Hardy of Urdu literature’ as well as many other crooks, swindlers and snake oil salesmen (and women).

Chakiwara is responsible for producing these characters. According to Changezi, the town is ‘a truly autonomous state where anyone can pass themselves off as anything’. Perhaps only in Chakiwara can a broke writer wander around in robes and claim to be a professor, a washed-up actor attempt to become a dentist and where promises of a supernatural nature are guaranteed only by a cheque deposited in the mail. Though Chakiwara may seem like a bizarre place to live, there is a certain honesty in the way its residents are portrayed. After all, in real life, few people are exactly who they say they are and everyone is a bit of a crook.

Akhtar has ensured his own stories cannot be boxed into a single genre

Instances in the collection that are particularly enjoyable range from Changezi’s meditations on balcony love; ‘the only form of love possible in this country is balcony love (and it shall continue to be so for at least another half a century)’, efforts to fit in at a swanky party only to discover that one of their friends fits in a little too well and the many hilarious yet unproductive meetings that take place at the Ghareeb Nawaz Hotel. Though these incidents differ, they all showcase Akhtar’s masterful ability to depict the irony and humour of everyday life.

Unlike the formulaic detective novels that Changezi devours and Kattar writes, Akhtar has ensured his own stories cannot be boxed into a single genre. They are narrated by young, single men but these are not coming-of-age stories – though some lessons are learnt along the way. They contain elements of the supernatural but djinns and mystics are not allowed to become the focus of the stories.These are not sob stories but they do contain moments of real loss and instances of poverty. They are not romances but depict both the pursuit and futility of love. Akhtar also ensures that the stories are situated in what is essentially a Pakistani town. Chakiwara is hardly paradise and there is plenty of racism, classism and sexism to go around.

On his translation of Love In Chakiwara, Bilal Tanweer says he translated Muhammad Khalid Akhtar’s work while paying particular attention to his narrative voice which he says ‘embodies most fully his ironic, mischievous, sophisticated sensibility as a writer.’ Tanweer has managed to produce a translation that is a joy to read; fresh and funny but also fully accessible to an English audience. Though every translation must accept its limitations, Tanweer has ensured that very few readers will feel they have missed out. It is likely that they will be too busy chuckling at Changezi and his bohemian friends as they struggle against the drama of life in Chakiwara.

Just because Akhtar’s chosen narrative voice is never fixed – sometimes dramatic, sometimes flippant and gossipy – and refuses to take itself too seriously does not mean he is an unsophisticated writer. Style is simply the manner in which the writer wishes to tell the story. This narrative voice, with all its charm and humour, carries these stories forward but is also able to effortlessly convince readers of the endless possibilities of life – and love – in Chakiwara. Perhaps what Muhammad Khalid Akhar truly wanted was to tell stories that reflected how absurd and impossible to predict or control life really is.