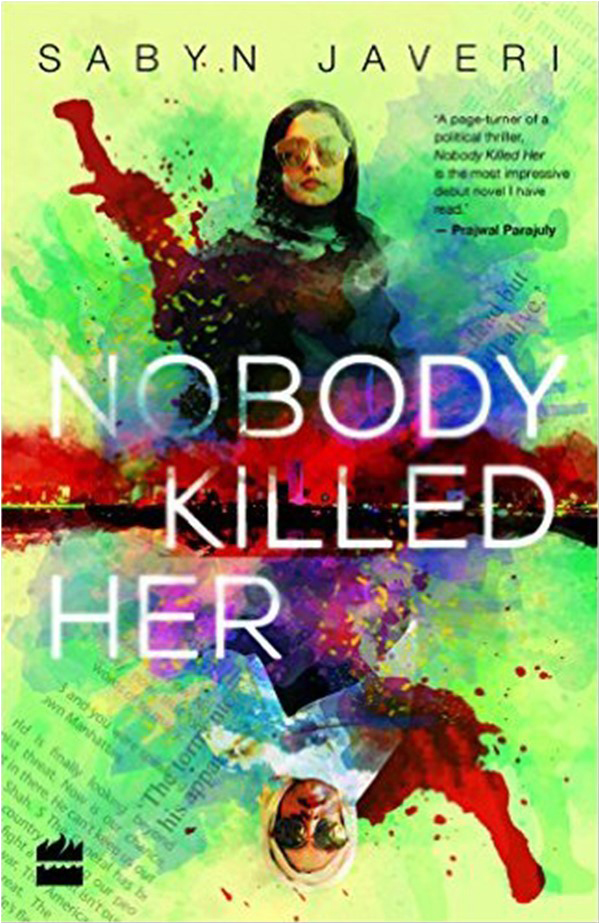

The cover of Sabyn Javeri’s long awaited debut novel is striking. Two women in headscarves and sunglasses emerge out of bright splashes of colour. Look a little closer and you’ll realise some of that colour is blood. If anything, the cover is an indication that the writer has set out to write a novel that dares to be different. Javeri admits that part of her motivation to write a political thriller came from the fact that it is not often regarded as a ‘woman’s genre’. The novel, of course, completely destroys this assumption. It is also a rare example of a story that is both fun to read - in the way that a political thriller should be - but also poses some weighty questions.

Most conversations that revolve around Nobody Killed Her focus on identifying who Rani Shah is based on. Is Javeri really writing about the life of Benazir Bhutto? Does she have information about BB that the rest of us somehow didn’t manage to get our hands on? Or is she writing about another female Muslim leader? These speculations have resulted in some accusations of misrepresentation - which Javeri shrugs off, reminding us that she did not set out to write a biography. Nobody Killed Her is, after all, a fictional exploration of politics.

Nobody Killed Her is a far cry from the simplistic narratives that we generally encounter on the subject of South Asian women and politics

Conversations about Rani Shah and who she really is prevent us from reflecting upon other aspects of the novel that deserve our attention. In fact, I would say that Rani Shah isn’t even the most interesting character in the novel. Sure, she knows how to make her presence felt. She is beautiful and she is assertive but these are predictable traits considering how much privilege she comes from. She is also too changeable to pin down as the novel hands her several roles which she constantly tries to fill. Rani strives to be a symbol of power and progress but can we really ever understand the people who we put up on such a pedestal?

The woman who really deserves our attention therefore is not Rani Shah but her Personal Assistant, Nazneen Khan (Nazo) whose entire family was killed by the General. Javeri has created a character who should be so vulnerable; a woman with no money of her own and no family to speak of and instead we are constantly surprised by her agency, frustrated by her love for her leader and shocked by how well she learns to play the game of politics.

Each chapter begins with some exposition delivered courtroom style which grounds readers to the present day where the murder of Rani Shah is being investigated. However, the rest of the story is told from Nazo’s perspective. She is essentially telling Rani the story of how it all happened. This is particularly jarring because Rani was there the whole time, so the question remains: how did she not see what was happening? Javeri ensures that readers cultivate a sense of empathy towards Nazo as time and time again we see her put in a difficult position, sometimes put there by Rani but also by other characters - mostly men - in the novel.

The novel follows Nazo and Rani from New York to Pakistan and documents not just Rani’s rise to power but also the many years that she is in power. As her PA and friend, Nazo deals with everything from Rani’s personal appointments to physically fending off people who try to attack her. Class and gender are the main concerns of the novel but the work also looks at the messy realities of politics and power. Some may complain that the novel is trying to do too much. But if a writer sets out to explore a poor woman’s negotiation with politics can the story ever be a simple one?

Why write a novel in this way? A fictional exploration of politics is not a way for writers or readers to point fingers. Javeri claims that works like this allow writers to ask “What if?” It allows readers to imagine the possibility of someone from the wrong gender and the wrong class who still has ambition. Fiction permits writers the space to step away from these neat narratives and be able to tell complicated stories. Nobody Killed Her is a far cry from the simplistic narratives that we generally encounter on the subject of South Asian women and politics. It is a great example of the sort of storytelling we should all be demanding more of.