The Pakistan constitution says that a national population census must be held every ten years. This is the norm in most countries because census data on various dimensions of state, economy and society is a critical input into equitable and efficient socio-economic and political development policy in any country. But Pakistan’s modern political leaders have been so wedded to the status quo in core areas of policy that the last census was held in 1998 after a gap of 17 years and the next census is scheduled this month after a gap of 19 years. Indeed, if it hadn’t been for ex-Chief Justice of Pakistan, Anwar Jamali, who took suo motu notice last year of this constitutional failing and ordered it to be conducted, it might never have been commissioned this year at all. Who’s afraid of the big bad census and why?

Federal governments are wary of conducting a census because it means painful and unending squabbles with provincial governments over how to share the federal income with them from federal taxes based on their share of the population. Inevitably, since population growth rates vary from province to province in view of their demographic profiles, there are winners and losers from each census. This is the main reason why the yearly National Finance Commission Award is subject to much stress and strain following updated projections of demographic change based on the latest census results. Since census data also includes data on the rural-urban divide and therefore impinges on the demand for water for irrigation purposes, it affects water sharing formulas between upper and lower riparian provinces that are mediated by the federal government. This, too, is a matter of controversy, especially if the political governments in the disputing provinces and the federal government have different vested interests. Federal governments also tend to be circumspect about the party political impact of population growth and consequent increase in number and location of electoral constituencies.

Provincial governments are also apprehensive about census results that create demand for hundreds of new rural and urban constituencies because this inevitably leads to the demand for more financial and administrative devolution of power, which provincial governments are loath to concede. The demographic shift from rural areas to urban areas also has implications for party political fortunes in view of different voter patterns and preferences. Given their dogged reluctance to hold local body elections for much the same reason – their fate has followed the same trajectory as that of the census, and the supreme court had to step in and order the provinces to stop making excuses and hold these after all – it is no wonder that a new census is not the most important item on provincial agendas.

There are specific provincial issues too. A new census is likely to create ethnic strife in Balochistan if the Afghan refugees – who number anywhere from one to two million – and who have national ID cards are included in it. This will tilt the ethnic balance in favour of the Pakhtuns and give them significantly greater representation in the provincial parliament to the detriment of the ethnic Baloch.

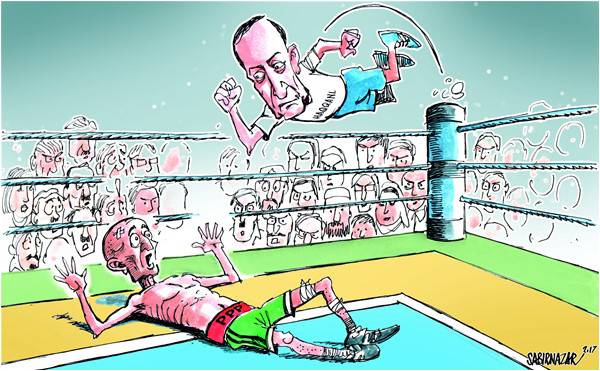

In Sindh, the urban Mohajir community will be a net loser in terms of job quotas and electoral prospects because its population growth rate is lower than that of rural Sindhis. The migration of ethnic Pakhtuns from FATA and KP (with high birth rates) to Karachi will also adversely impact on Mohajir prospects. The fact that the ruling PPP draws its strength from the rural areas but wants to make inroads into Karachi, and the MQM, JUI, JI, ANP and PTI are all vying for the urban vote, will result in intense jostling among the mainstream parties and factions for a slice of the action following urban constituency increase and delimitation. Sindh is also apprehensive that it may be at a grave disadvantage because over 25 per cent of the population in the rural areas doesn’t have national ID cards.

The only province that is likely to be a clear winner from the new census on most counts is Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. KP can expect to see an increase in its share of the federal divisible pool of income (at the expense of the Punjab) on the basis of both a higher than average birth rate plus inclusion of a couple of million Afghan refugees with Pakistan ID cards. This is going to increase with the absorption of FATA in the province as announced.

The new Census will also provide grist for disadvantaged and underdeveloped areas and sections of the polity. Where inequalities are glaring, as in gender or regions or on account of ethnicity, vis a vis social indicators of health, education and poverty, the demand for justice and positive discrimination will be loud and clear.

In short, the new census is going to shake the already highly contentious status quo in many areas of nation building and political and economic evolution. That is why there isn’t much enthusiasm for it in the ruling establishment.

Federal governments are wary of conducting a census because it means painful and unending squabbles with provincial governments over how to share the federal income with them from federal taxes based on their share of the population. Inevitably, since population growth rates vary from province to province in view of their demographic profiles, there are winners and losers from each census. This is the main reason why the yearly National Finance Commission Award is subject to much stress and strain following updated projections of demographic change based on the latest census results. Since census data also includes data on the rural-urban divide and therefore impinges on the demand for water for irrigation purposes, it affects water sharing formulas between upper and lower riparian provinces that are mediated by the federal government. This, too, is a matter of controversy, especially if the political governments in the disputing provinces and the federal government have different vested interests. Federal governments also tend to be circumspect about the party political impact of population growth and consequent increase in number and location of electoral constituencies.

Provincial governments are also apprehensive about census results that create demand for hundreds of new rural and urban constituencies because this inevitably leads to the demand for more financial and administrative devolution of power, which provincial governments are loath to concede. The demographic shift from rural areas to urban areas also has implications for party political fortunes in view of different voter patterns and preferences. Given their dogged reluctance to hold local body elections for much the same reason – their fate has followed the same trajectory as that of the census, and the supreme court had to step in and order the provinces to stop making excuses and hold these after all – it is no wonder that a new census is not the most important item on provincial agendas.

There are specific provincial issues too. A new census is likely to create ethnic strife in Balochistan if the Afghan refugees – who number anywhere from one to two million – and who have national ID cards are included in it. This will tilt the ethnic balance in favour of the Pakhtuns and give them significantly greater representation in the provincial parliament to the detriment of the ethnic Baloch.

In Sindh, the urban Mohajir community will be a net loser in terms of job quotas and electoral prospects because its population growth rate is lower than that of rural Sindhis. The migration of ethnic Pakhtuns from FATA and KP (with high birth rates) to Karachi will also adversely impact on Mohajir prospects. The fact that the ruling PPP draws its strength from the rural areas but wants to make inroads into Karachi, and the MQM, JUI, JI, ANP and PTI are all vying for the urban vote, will result in intense jostling among the mainstream parties and factions for a slice of the action following urban constituency increase and delimitation. Sindh is also apprehensive that it may be at a grave disadvantage because over 25 per cent of the population in the rural areas doesn’t have national ID cards.

The only province that is likely to be a clear winner from the new census on most counts is Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa. KP can expect to see an increase in its share of the federal divisible pool of income (at the expense of the Punjab) on the basis of both a higher than average birth rate plus inclusion of a couple of million Afghan refugees with Pakistan ID cards. This is going to increase with the absorption of FATA in the province as announced.

The new Census will also provide grist for disadvantaged and underdeveloped areas and sections of the polity. Where inequalities are glaring, as in gender or regions or on account of ethnicity, vis a vis social indicators of health, education and poverty, the demand for justice and positive discrimination will be loud and clear.

In short, the new census is going to shake the already highly contentious status quo in many areas of nation building and political and economic evolution. That is why there isn’t much enthusiasm for it in the ruling establishment.