Mistrust with Kabul has existed for ages, but the recent wave of terrorism has underscored how it can pose a serious national security dilemma, more so at a time when gains against terrorism made during Operation Zarb-e-Azb are being consolidated.

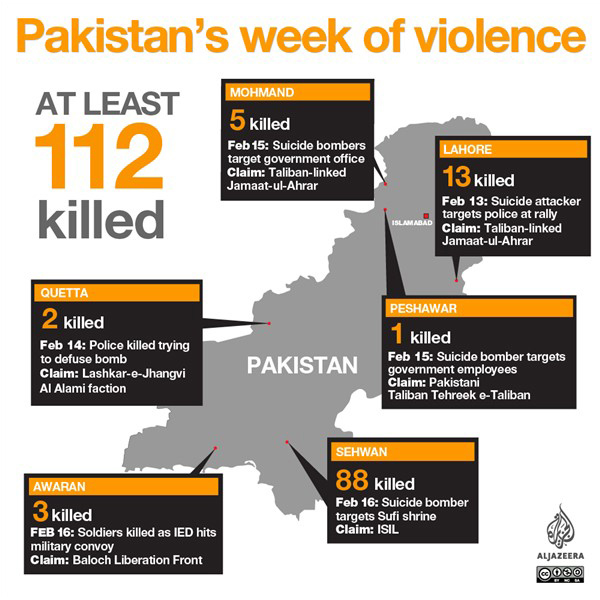

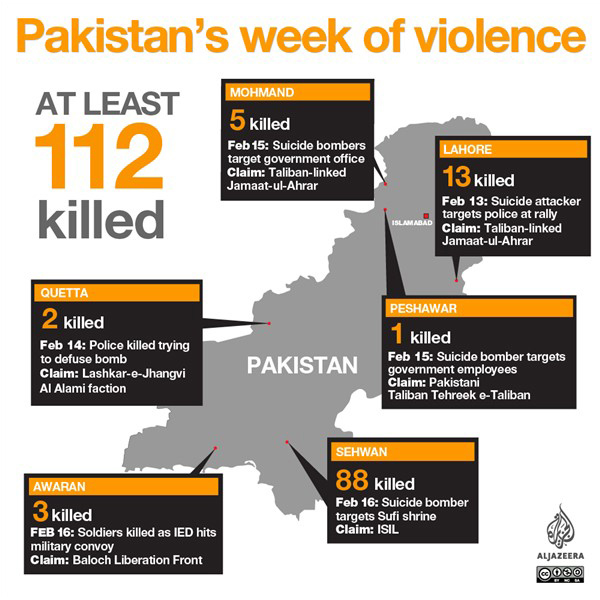

Focus turned to Afghanistan as soon as terrorist groups that had fled counter-terrorism operations and taken up refuge on Afghan soil, hit back to remind of their existence. In the course of three days in Pakistan 112 people were killed in six terrorist attacks. The Jamaat-ul-Ahrar, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and Tehreek-e-Taliban, even ISIL, claimed responsibility for the attacks. But this time the official response was not to trade barbs. Instead the Pakistan Army took the lead in conveying a strong message to Kabul that inaction against the sanctuaries of terror groups targeting Pakistan on its soil was tolerable no more. Pressure on Kabul was ramped up; the border crossings were immediately closed and a list of 76 wanted terrorists was handed over. Hideouts adjacent to the international boundary were shelled.

In a fit of anger, it was forgotten that the existence of sanctuaries was not a new issue, and Kabul, which had been asked several times before to get rid of them and whom all our pleadings and persuasions had failed to spur into action, cannot be steamrolled into doing so. The argument that a display of ‘courage’ would enhance Pakistan’s negotiating position probably prevailed at GHQ. The only time Afghanistan has taken action against Pakistani terrorists on its territory was after the Army Public School attack, when Kabul wanted a reset in the relationship and had expectations that Islamabad would facilitate reconciliation with the Taliban. A bonhomie had existed (in Dec 2014) and when the then Army Chief Gen Raheel Sharif flew from Peshawar to Kabul immediately after the APS carnage, armed with intelligence that the gruesome act had been directed from Afghan soil, he was obliged.

This time round, the situation is completely different. The Afghans are not only annoyed, but also in a non-cooperative mode. Yes, COAS Gen Qamar Bajwa has, over the past few weeks, prior to the latest series of attacks, been trying to engage them. But the Army’s strong response after being hit by terror caused an escalation in tensions instead of having the effect of prodding Kabul into addressing our concerns. Afghanistan pointed fingers back at Pakistan, handing over a list of 85 Taliban and Haqqani Network militants, including Maulvi Haibatullah and Siraj Haqqani, and 32 training camps. This blunted Pakistan’s diplomatic offensive to highlight the presence of terror sanctuaries in Afghanistan. The shelling in the border districts of Nangarhar (Goshta and Lalpor) and Kunar (Sarkano) provinces of Afghanistan, meanwhile, added to anti-Pakistan sentiment within Afghanistan, where this was seen as aggression from a neighbor and a violation of sovereignty.

Afghanistan may not be a match for Pakistan, but somehow the Afghans did try to muster the rhetoric. So when Pakistan Army began moving its big guns to the border, similar intentions were expressed by the people in Kabul. The debate about their capabilities notwithstanding, the Afghan media quoted unnamed officials saying: “Fresh troops and heavy weapons had been sent to the zero point area of Nangarhar border with Pakistan. Forces were ordered to be on standby and respond in case of more rocket attacks by Pakistan.”

Tensions mainly escalated this time because of the absence of an effective security cooperation mechanism and our knee-jerk reaction. At the same time, the escalation underscored the perils of allowing the military to drive external relations. There was a sharp difference in the way the Foreign Office and GHQ had handled the matter. Throughout the episode, the FO, unlike GHQ, appeared to be more understanding of Afghanistan’s constraints in dealing with terrorism.

“Turmoil in Afghanistan, which is persisting for almost forty years now and especially the current situation in the last few years, has created space for the violent non-state actors and terrorist organizations to find their foothold there,” FO Spokesman Nafees Zakaria said. “We took up the issue with the Afghan Deputy Head of Mission because the responsibility for the Lahore terrorist attack was claimed by Jamaat-ul-Ahraar, which is based in Afghanistan. This is what we have been talking about. We urged the Afghan side earlier, and this time also, to take necessary steps to address our concerns in this regard. We remain committed to provide all necessary support and cooperation to bring about peace and stability in Afghanistan.”

But luckily, as the initial emotions died down, both sides appeared cognizant of the need to cooperate against terrorism, which was seen as a “common enemy”. Therefore, when Gen Qamar Bajwa sat down with his commanders to review the situation after days of blowing hot, he appeared to be realizing that cooperation not confrontation can make Afghanistan deliver.

“Pakistan and Afghanistan have fought against terrorism and shall continue this effort together,” he told his commanders. “Enhanced security arrangements along the Pak-Afghan border were for fighting a common enemy.”

Similar vibes have been coming from Kabul as well, where officials privately say the government has been mulling over the prospects of intelligence and security cooperation with Pakistan. There have been two botched efforts in the past, in 2015 and 2016, to forge intel ties. Each attempt failed because of resistance to the idea in Afghanistan. One cannot say with confidence what the chances of success will be for this new attempt, but it is still encouraging that such a move is being considered.

Now that Afghan Ambassador to Pakistan Omar Zakhilwal has said he expects a “quick de-escalation of the current tension and the creation of a more positive environment for responding to each other’s concerns and grievances in a cooperative manner,” there is certainly all the reason to be hopeful.

For Pakistan and Afghanistan to translate good intentions into action, they need to address the issue of sanctuaries, which has continued to bedevil ties. There is logic in Pakistan’s point that terrorists based on Afghan soil have been behind the latest string of attacks, but at the same time Kabul’s contention isn’t entirely baseless that Afghan Taliban would not have been able to sustain their insurgency without external backing.

Both Islamabad and Kabul need to realize that they have too much at stake not to be cooperating. Space for terrorist groups to operate can only be reduced through cooperation between the two countries, while a disconnect only gives them a ripe environment to thrive.

The writer is a freelance journalist based in Islamabad and can be reached at mamoonarubab@gmail.com and @bokhari_mr

Focus turned to Afghanistan as soon as terrorist groups that had fled counter-terrorism operations and taken up refuge on Afghan soil, hit back to remind of their existence. In the course of three days in Pakistan 112 people were killed in six terrorist attacks. The Jamaat-ul-Ahrar, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and Tehreek-e-Taliban, even ISIL, claimed responsibility for the attacks. But this time the official response was not to trade barbs. Instead the Pakistan Army took the lead in conveying a strong message to Kabul that inaction against the sanctuaries of terror groups targeting Pakistan on its soil was tolerable no more. Pressure on Kabul was ramped up; the border crossings were immediately closed and a list of 76 wanted terrorists was handed over. Hideouts adjacent to the international boundary were shelled.

In a fit of anger, it was forgotten that the existence of sanctuaries was not a new issue, and Kabul, which had been asked several times before to get rid of them and whom all our pleadings and persuasions had failed to spur into action, cannot be steamrolled into doing so. The argument that a display of ‘courage’ would enhance Pakistan’s negotiating position probably prevailed at GHQ. The only time Afghanistan has taken action against Pakistani terrorists on its territory was after the Army Public School attack, when Kabul wanted a reset in the relationship and had expectations that Islamabad would facilitate reconciliation with the Taliban. A bonhomie had existed (in Dec 2014) and when the then Army Chief Gen Raheel Sharif flew from Peshawar to Kabul immediately after the APS carnage, armed with intelligence that the gruesome act had been directed from Afghan soil, he was obliged.

This time round, the situation is completely different. The Afghans are not only annoyed, but also in a non-cooperative mode. Yes, COAS Gen Qamar Bajwa has, over the past few weeks, prior to the latest series of attacks, been trying to engage them. But the Army’s strong response after being hit by terror caused an escalation in tensions instead of having the effect of prodding Kabul into addressing our concerns. Afghanistan pointed fingers back at Pakistan, handing over a list of 85 Taliban and Haqqani Network militants, including Maulvi Haibatullah and Siraj Haqqani, and 32 training camps. This blunted Pakistan’s diplomatic offensive to highlight the presence of terror sanctuaries in Afghanistan. The shelling in the border districts of Nangarhar (Goshta and Lalpor) and Kunar (Sarkano) provinces of Afghanistan, meanwhile, added to anti-Pakistan sentiment within Afghanistan, where this was seen as aggression from a neighbor and a violation of sovereignty.

Afghanistan may not be a match for Pakistan, but somehow the Afghans did try to muster the rhetoric. So when Pakistan Army began moving its big guns to the border, similar intentions were expressed by the people in Kabul. The debate about their capabilities notwithstanding, the Afghan media quoted unnamed officials saying: “Fresh troops and heavy weapons had been sent to the zero point area of Nangarhar border with Pakistan. Forces were ordered to be on standby and respond in case of more rocket attacks by Pakistan.”

Gen Qamar Bajwa told his commanders that Pakistan and Afghanistan fight a common enemy. Similar vibes have been coming from Kabul as well, where officials privately say the government has been mulling over the prospects of intelligence and security cooperation with Pakistan

Tensions mainly escalated this time because of the absence of an effective security cooperation mechanism and our knee-jerk reaction. At the same time, the escalation underscored the perils of allowing the military to drive external relations. There was a sharp difference in the way the Foreign Office and GHQ had handled the matter. Throughout the episode, the FO, unlike GHQ, appeared to be more understanding of Afghanistan’s constraints in dealing with terrorism.

“Turmoil in Afghanistan, which is persisting for almost forty years now and especially the current situation in the last few years, has created space for the violent non-state actors and terrorist organizations to find their foothold there,” FO Spokesman Nafees Zakaria said. “We took up the issue with the Afghan Deputy Head of Mission because the responsibility for the Lahore terrorist attack was claimed by Jamaat-ul-Ahraar, which is based in Afghanistan. This is what we have been talking about. We urged the Afghan side earlier, and this time also, to take necessary steps to address our concerns in this regard. We remain committed to provide all necessary support and cooperation to bring about peace and stability in Afghanistan.”

But luckily, as the initial emotions died down, both sides appeared cognizant of the need to cooperate against terrorism, which was seen as a “common enemy”. Therefore, when Gen Qamar Bajwa sat down with his commanders to review the situation after days of blowing hot, he appeared to be realizing that cooperation not confrontation can make Afghanistan deliver.

“Pakistan and Afghanistan have fought against terrorism and shall continue this effort together,” he told his commanders. “Enhanced security arrangements along the Pak-Afghan border were for fighting a common enemy.”

Similar vibes have been coming from Kabul as well, where officials privately say the government has been mulling over the prospects of intelligence and security cooperation with Pakistan. There have been two botched efforts in the past, in 2015 and 2016, to forge intel ties. Each attempt failed because of resistance to the idea in Afghanistan. One cannot say with confidence what the chances of success will be for this new attempt, but it is still encouraging that such a move is being considered.

Now that Afghan Ambassador to Pakistan Omar Zakhilwal has said he expects a “quick de-escalation of the current tension and the creation of a more positive environment for responding to each other’s concerns and grievances in a cooperative manner,” there is certainly all the reason to be hopeful.

For Pakistan and Afghanistan to translate good intentions into action, they need to address the issue of sanctuaries, which has continued to bedevil ties. There is logic in Pakistan’s point that terrorists based on Afghan soil have been behind the latest string of attacks, but at the same time Kabul’s contention isn’t entirely baseless that Afghan Taliban would not have been able to sustain their insurgency without external backing.

Both Islamabad and Kabul need to realize that they have too much at stake not to be cooperating. Space for terrorist groups to operate can only be reduced through cooperation between the two countries, while a disconnect only gives them a ripe environment to thrive.

The writer is a freelance journalist based in Islamabad and can be reached at mamoonarubab@gmail.com and @bokhari_mr