In an age when fears of proliferation of weapons of mass destruction abound, it is the use of human bombs by terrorist groups which remains one of the most lethal weapons to have been employed in warfare in recent times. The suicide bombing at a Quetta hospital on August 8 came as a reminder of just how much damage this tactic can wreak.

In an age when fears of proliferation of weapons of mass destruction abound, it is the use of human bombs by terrorist groups which remains one of the most lethal weapons to have been employed in warfare in recent times. The suicide bombing at a Quetta hospital on August 8 came as a reminder of just how much damage this tactic can wreak.The debate on what drives men, women and children to let someone strap on a bomb has largely focused on poverty and misinterpretation of religion. The indiscriminate use of suicide bombing continues to test the ability of states and law enforcement agencies to come up with ways to prevent it. The academic and lay public are still largely bewildered with how a person can choose to “use their bones as bullets, their flesh as gunpowder and their blood as fuel”. But a new book, The Making of Pakistani Human Bombs by Assistant Professor Dr Khuram Iqbal of National Defense University, challenges these notions by presenting comprehensive research on one of the most common and yet least understood weapons of terror. The work is timely given that Pakistan is one of the worst hit countries by suicide bombers. The phenomenon has, surprisingly, rarely, however, been the topic of empirical and theoretical research even though, since 2002, 439 such attacks have claimed an estimated 6,600 lives and wounded another 13,735.

An important contribution of the study is to make a comparison of Pakistani suicide bombers with their counterparts from Palestine, Lebanon, Turkey, Chechnya and Sri Lanka

Iqbal has interacted with failed suicide bombers captured by law enforcement agencies and studied the profiles of other suicide bombers. He concludes that suicide bombing cannot be explained by a single phenomenon and is actually the outcome of an interplay of multiple factors at three levels: individual, organizational and environmental.

One common myth, for example, is that one motivating factor is to exact revenge against drone strikes by the United States in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas or to punish the Pakistani state for what the suicide bomber perceives as cooperation with the US in the fight against terrorism. Iqbal questions this theory of ‘revenge’ as his findings indicate that these are not the primary factors that promote terrorism in all its manifestations.

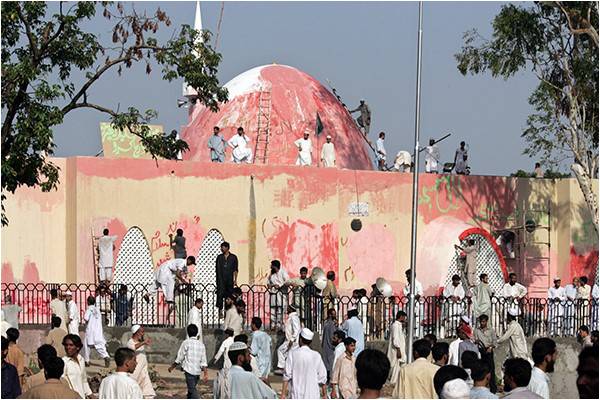

Some clues lie in history. The roots of suicide bombings in Pakistan date to 1995 when an Al-Qaeda operative rammed an explosives-laden pickup truck into the Egyptian Embassy in Islamabad, killing 15 people and injuring 59 others. And thus, Iqbal contends that the idea of suicide bombing was a foreign import and largely remained unpopular till the Lal Masjid stand-off between the militants and state in 2007. The dramatic siege of the mosque complex fed a local impetus and was used as a recruiting cry first by the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan and later by other groups as well. Until the Lal Masjid operation, there had been 14 suicide attacks in Pakistan but after it there were 47 suicide bombings in the second half of 2007 alone, registering a sharp spike in the bombings as well as recruitment and public support.

Suicide terrorism is preferred for what organisations perceive as its ‘effectiveness’, for its ability to exact revenge for perceived injustices against Muslims in general, poverty and religious fundamentalism. Iqbal contends that nationalism or resistance to foreign occupation are the least relevant factors. While religious fundamentalism provides credible ideological justification necessary to motivate individual recruits to conduct such operations, relative or absolute poverty in conflict-hit areas of Pakistan is a motivating factor for individuals. The act of a suicide attack or ‘fidayeen’ is also considered something that elevates the social status and prestige of the bomber’s family. Iqbal notes that the TTP used to issue certificates of martyrdom in South Waziristan which families displayed in their hujras.

On the basis of a study of demographic background and interviews with failed suicide bombers, Iqbal found that retribution for personal anguish was rarely a motivator. Instead, terrorist organisations skilfully manipulate an individual’s sense of the general suffering of Muslims at home and globally. This study thus discredits the general belief that suicide attacks are carried out by uneducated, impoverished and psychologically challenged people who have largely failed to achieve anything in life and can aspire to nothing other than a glorified death with a promise of entering heaven.

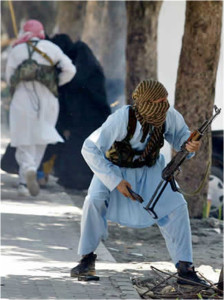

Militant organizations also prefer this tactic because of its perceived effectiveness. An attack not only attracts media attention but it also easily penetrates and targets high-profile people and creates an environment of fear among the public with minimal effort. However, Iqbal also notes that, “The strategic effectiveness of employing the tactic of suicide bombings has also cost terrorist groups much public support due to indiscriminate targeting of civilians.” A higher percentage of civilians have been killed.

The study, which uses personal profiles, demographic data and economic and marital status data of suicide bombers, reveals that the average age of the Pakistani bomber is 18 years and they are mostly (86%) single, semi-literate in terms of education acquired at either an informal madrasa or the formal sector, and they mostly come from rural centers. However, many have also come from urban centers, including the northern parts of Punjab. This puts a dent in the ethnic profiling of suicide bombers; while it is true that a majority comes from Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and FATA, over 17% of suicide bombers come from Punjab, 9% are foreigners, 5% come from Balochistan and the others from Sindh and Azad Jammu and Kashmir.

Another important contribution of the study is to make a comparison of Pakistani suicide bombers with their counterparts from Palestine, Lebanon, Turkey, Chechnya and Sri Lanka. The comparison reveals that the Pakistani suicide bombers are younger as well as more deadly than the others, which should be a cause of worry for policy makers given the youth bulge in Pakistan. However, as the Pakistani case study demonstrates, even though the tactic may be the same, every country has unique characteristics and therefore the phenomenon needs to be understood and countered through a context-specific and multi-level approach, which should include broader counter radicalization reforms aimed at the younger population of the country.

Since Iqbal has taken an academic approach to the book, it largely appears objective in its analysis of the issues associated with suicide bombings in Pakistan and their ideological origins. However, as the author clearly concedes, the lack of available data and the unwillingness of law enforcement agencies to share information hampers large-scale studies. Given the limitations of the study, though, it still ranks as the best available one on the topic in Pakistan and should be equally valuable for students and academics of counter-terrorism, law-enforcing agencies, government and military officials to understand the threat posed by suicide bombing and to review their strategies to counter it in Pakistan.