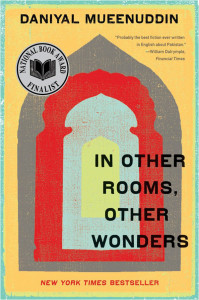

I must confess that in my initial reading of Daniyal Mueenuddin’s collection of short stories In Other Rooms, Other Wonders, I felt disappointed. Perhaps, I had stuck the lens of feminism too hard on my eyes which gave me the impression that his stories were nothing more than a cold-hearted account of socially stranded poor women and their petty exploitation in a feudal household. In the first quick reading it seemed that these women were the exploiters. It was not until Qandeel Baloch’s murder that I felt the urge to revisit Mueenuddin’s writings, which is where I found a way to decipher the honour-dishonour muddle, especially in the part of Punjab which Baloch and many like her come from - some get killed and others don’t. It was my second reading of the book that helped pick out threads of how honour and revenge for dishonour operated in the heart of rural Punjab, and surely other similar places as well.

I must confess that in my initial reading of Daniyal Mueenuddin’s collection of short stories In Other Rooms, Other Wonders, I felt disappointed. Perhaps, I had stuck the lens of feminism too hard on my eyes which gave me the impression that his stories were nothing more than a cold-hearted account of socially stranded poor women and their petty exploitation in a feudal household. In the first quick reading it seemed that these women were the exploiters. It was not until Qandeel Baloch’s murder that I felt the urge to revisit Mueenuddin’s writings, which is where I found a way to decipher the honour-dishonour muddle, especially in the part of Punjab which Baloch and many like her come from - some get killed and others don’t. It was my second reading of the book that helped pick out threads of how honour and revenge for dishonour operated in the heart of rural Punjab, and surely other similar places as well.While I was growing up in South Punjab it was a rarity to hear of honour killing. Women eloped and stayed alive. Some even returned and were not sacrificed to male honour. Indeed, it is still rare. How could you apply the principle of honour across the board when the rich young feudal master would loose their virginity to a housemaid, and those not so rich would try their muscles in the fields with women of their own socioeconomic class or even an animal? Does the pir or syed, who is the spiritual lord of a dargah, think he is violating the honour of women who he physically abuses in the name of exorcism or as a sacrifice to his spiritual label? Every village knows who sleeps in whose bed. A friend once pointed out how the faces of the children of a couple of women in my village resembled her but not each other.

So, when Jaglani, a neo-feudal character from Mueenuddin’s story inquires from Zenab, his housemaid and mistress, if she is afraid of spending the night with him due to fear of village gossip, her response is: “The villagers! They knew the first night. They leave me alone because they are afraid of you….if you dropped me they would call me a whore out loud as I walked down the street.” This is the story of a married woman, who is resigned to the exercise of power in a feudal system. But more importantly, she wants to manipulate the system to get what she wants most - a child which she thinks she can’t have due to her husband’s perceived impotence. It is later that she finds the problem is actually with her.

Would we call Zainab a whore despite that she fully understands that this is exactly the term used for her in the village? Or should we imagine that another character from Mueenuddin’s short story, Husna, does not have a sense of honour and pride, as she crawls towards her rich and older uncle double her age? But unlike Zainab, Husna is unsure about the price of her honour and the reward for her services. She gets upset by the treatment meted out to her by the landlord uncle’s urban and educated daughter and servants, who treat her according to her class, and so complains: “I gave you everything I had, but you give me nothing in return. I have feelings too, I am human…” Dive inside Daniyal Mueenuddin’s anthology of short stories and you find honour belongs to the powerful, which in a rural society pertains to male and upper class with capacity to exploit both the underling and the system to its advantage. His stories are not about exploitation by the poor woman but her vulnerability to a power structure that only has place for the rich and power-hungry. Hence, the real threat is poverty or being socially and politically a nobody. These are some of the sins for which you can get punished, with all of it made to look like retribution for dishonouring yourself, your family or the social norms.

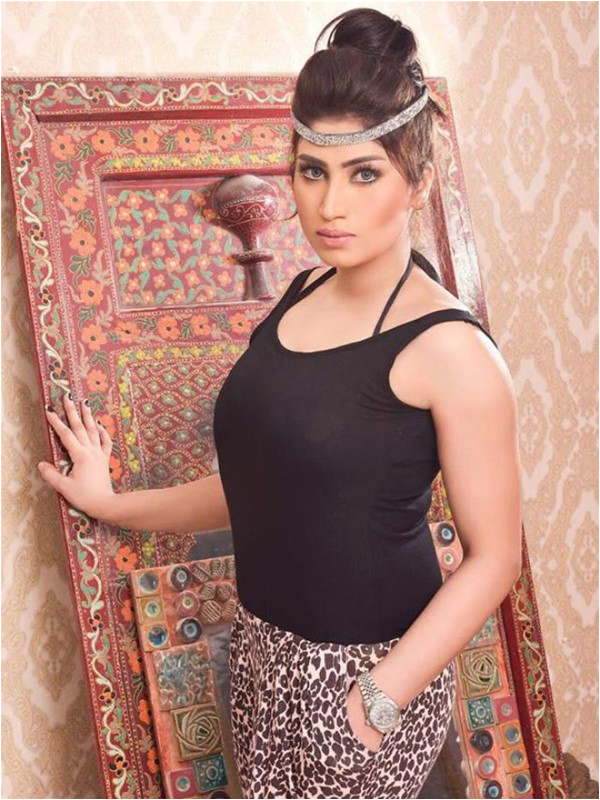

Qandeel Baloch from DG Khan’s sin was not that she crossed limits or comfortably traded her looks for greater opportunities. Perhaps her lapse was understanding how the social power structure protected one of its own against women like her who came from a less exciting social background. Would a woman that called out the hypocrisy of a prominent mullah stop there? Hadn’t she become a threat to powerful men who would want to exploit her without retribution or at no high cost? So, who is interested in investigating the death of a rebel? Baloch got ditched and killed not just by her brother, who may have killed her due to some incident (the story of which we will never find out), but at the hands of a far more brutal social mechanism. She was not different from how the fictional Husna and Zenab get treated at the end. In Zainab’s case the big landowner, who eventually marries her for fear of bad press during elections, finally abandons her to poverty and fate. When he dies of cancer he is struck with remorse on shaming his children from his first wife. Jaglani’s honour doesn’t allow him to own Zenab. Similarly, when the uncle-feudal landowner Harouni dies of old age, Husna is packed off with some petty cash. Thus, Qandeel, Husna and Zenab are all slaughtered by the system to sustain the honour of the powerful.

In South Punjab, honour killings have increased relative to the past, due to the particular evolution of the region and proliferation of power. Surely, the expansion of other ethnic groups such as the Pashtuns, Afghans and Punjabis have influenced the social conditioning of the society. It is not that Saraiki socities were inherently immoral but since most areas suffered from authoritarian rule and hegemonic power in which the feudal combined political, economic and spiritual power, ordinary people were not accustomed to an orthodox interpretation of religion or familiar with textual evidence regarding religious/ethical principles. It is really towards the end of the 20th century that orthodoxy was introduced in these areas. While it is influencing attitudes in many places, things continue to be the same in the larger region.

While I was growing up in South Punjab, it was a rarity to hear of honour killing. Women eloped and stayed alive

But an important factor worth looking at is proliferation of power centres. Although still largely a feudal area, the old feudal structure is in the process of gradual dilution. The new capital moving into or within the area has not brought development or noticeable social and human resource progress but generated a class of neo-feudal that range from trader-turned big tradesmen and new medium- to large landowners that try to copy feudal norms of absolute power. The expansion of media and wider means of communication create a certain tension. It is in the middle of this that you see ‘weaklings’ - that includes women - struggle. Those that aim for more without due care for the power structure are the ones that suffer. It is the contest that kills.

I am reminded of a video that had gone viral on YouTube just a few months ago that showed a rural festival in South Punjab in which a handful of dancing women had stripped on stage. Apparently, it excited some men in the audience to do the same. Yet it was equally impressive to see no one pounced at these women. For those that purposely leaked the video to target a particular prominent South Punjabi politician, who had come to inaugurate the event, the sighte of dancing women and the occasional striptease is not a rare event. Most festivals cater for a male audience. In fact, every Punjab town has commercial theaters meant for an all-male audience. Reportedly, the degree of uninhibitedness increases as the size of the town gets smaller. The generous use of expletives and verbal description of female genitalia mixed with exhibition of female body, though inside clothes, would make one forget a western striptease show. Irrespective that this entire drama is based on exploitation, the woman on the stage is protected by certain norms. I remember sitting through a couple of such shows in which the all-male audience, totally on heat, was discouraged from crossing a certain line. It was during one such show that I got a chance to speak to one of the dancing girls who was accompanied by her mother every time she performed. I asked if she performed in Gujranwala, a city where she came from, to which she responded in the negative. Her excuse was that it was her city. She was probably talking about the honour of her family, especially the males. Qandeel may not have died had she kept performing in her small social enclave, launching provocative videos but not challenging the powerful.

Those that aim for more without due care for the power structures are the ones that suffer

Power has a way of looking after itself, its honour and dishonour. It also has its own ways to sacrifice those that it fears may cross a line or have done so. Strangely enough, stories of the rich and powerful and their tragedies are rare. Barring My Feudal Lord by Tehmina Durrani, which is both a biography and an insight into brute power of the rural feudal mindset and its brutality, there is little that we find in terms of both fiction and non-fiction regarding the socially influential. There are stories worth writing about girls that are sacrificed to male honour by being held captive at home. This is not necessarily about physical captivity but mental and spiritual captivity. Combing major influential households will enable one to reap stories of females neither encouraged to study nor to get married, particularly outside the family.

Is this not another form of honour killing?

Dr. Ayesha Siddiqa is a civilian military scientist, author, former bureaucrat and political commentator. She tweets at @iamthedrifter