On June 27, the district administration of Lower Dir banned the sale toy guns for a month.

Deputy Commissioner Ifranullah Khan Wazir imposed the ban under Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code, which allows the district administration to prohibit any activity for a specific period of time in public interest.

According to a press note, the ban on toys that look like “guns, pistols and Kalashnikovs” was a response to complaints by parents, after a surge in the sale of such toys before Eid.

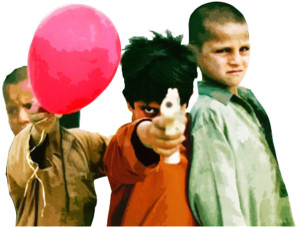

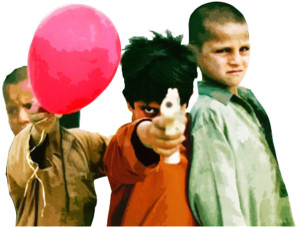

Toy guns are a popular item in the bazars of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the Pashtun-dominated tribal areas, especially on the occasion of holidays such as Eid. Some psychologists, civil right activists, educationists and parents have been calling for a broader ban on toy guns in these areas, arguing that playing with such toys leads children towards violence and crime.

A number of studies show no link between playing with toy weapons in childhood and aggression in adulthood, and most adult men who did engage in gunplay as children do not commit violent crimes. But the activity may be seen as dangerous when combined with a number of other social, psychological and security-related factors in the local context of FATA and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Amid a growing demand for such items ahead of Eid, Shakir Khan, a shopkeeper in the Adenzai tehsil of Lower Dir told me he had bought a large number of toy weapons before Ramzan. “The wholesale dealers raise the prices of toy weapons closer to Eid,” he said.

There was a wide variety of toy guns in his shop, cost anywhere between Rs 20 and Rs 350. Most of his customers are not affluent, he told me. I also saw a small plastic dagger for Rs 10.

In the wholesale market in Batkhela, the headquarters of Malakand Agency from where he and other shopkeepers buy in bulk, there were toy guns as expensive as Rs 2,000. The largest toy stores are in Mingora city in Swat, which is also the headquarters of Malakand division.

“Toys are toys, whether they are guns, vehicles or helicopters. They’re all the same,” said Shakir Khan. He disagreed with the notion that playing with toy guns would make children violent or aggressive. “Children who play with toy buses and trucks do not grow up to become drivers or conductors.”

But Muhammad Sajid, who runs a toyshop in the same area, does not sell toy guns and pistols. “Playing with guns promotes a violent culture,” he argued. “Sometimes children injure each other with plastic palettes too.”

According to Ahmad Ali, a wholesale dealer in Batkhela, toy weapons are the most popular item ahead of Eid. The pocket money, or Eidi, that children get on the day of the feast is spent on toys. Ahmad Ali said most boys prefer toy vehicles and toy guns, while most girls buy dolls and toy kitchenware. A large number of parents in rural areas are not even aware of the debate around the possible negative impacts of playing with toy guns, he said. “If they are banned, it would hurt the business and livelihoods of toyshop owners,” said Ahmad Ali.

“I think we should let the children decide whether they want to buy toy trucks or toy guns, or any other toys with their pocket money,” said Sheer Ghani, a father of three from Chakdara town. “It is the children who would play with those toys after all, and not us.”

But Muhammad Rahim, a parent from from Shergarh Mardan, said that he does not allow his children to buy toy guns. “If parents show some interest, it is not difficult to divert children’s attention from guns to other kind of toys,” he said.

Anas, a class-three student who lives in the Khadagzai village of Dir Lower, said all his cousins buy toy guns on Eid and play a gun battle game, often a police-versus-criminals roleplay. “We shoot at each other with plastic bullets.”

Burhan Marwat, an educationist from Sarai Naurang in Lakki Marwat, said it was his duty as a teacher to educate children about what kind of toys they should play with. “If parents are not aware of the harmful effects of toy guns, schools can play a role in discouraging such dangerous activities,” he said.

Hunar Koor, an organization promoting peace through skills-development, has been striving to end what it calls the “gun culture in Pashtun society”. The organization has carried out a number of campaigns in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the tribal areas to promote the use of educational toys. “Guns are not toys, they kill innocence. Instead of toy guns, children should be given toys that educate them,” said Amjad Shahzad, one of the founding activists at the organization.

Usman Ulasyar, chairman of the Suvastu Arts and Cultural Association, says such campaigns have educated a large number of parents about the negative impact of toy guns on their children. According to him, toy shops in Mingora city are much less likely to display toy guns and pistols than they were in the past.

A one-month ban under section 144 is not the solution, he says. “There should be legislation for a complete ban on the trade of toy guns.” Hunar Koor and Suvastu Arts and Cultural Association have jointly organized a number of seminars and awareness walks against weapons.

“Playing with toy guns in the militancy plagued Pashtun society appears to have a direct influence on violence and aggression,” according to Prof Dr Arabnaz Khan, chairman of the Department of Psychology at the University of Malakand.

“During the period of militancy in Malakand division, from 2007 to 2009, children developed new games while playing in the streets,” he said. “They shot at each other with toy guns, and made rocket launchers and mortar guns with empty beverage bottles, and grenades out of plastic bags filled with sand,” the professor said. “These games reflected what was happening around them. If the militancy had continued, children would have grown up and picked up real guns without hesitation.”

Toy gun battles would be harmless in a peaceful society where children have little access to real weapons, he said. “Even colorful toy guns would create problems in this part of the world. The only solution is to make them unavailable.”

Tahir Ali is a freelance reporter based in Islamabad

Deputy Commissioner Ifranullah Khan Wazir imposed the ban under Section 144 of the Criminal Procedure Code, which allows the district administration to prohibit any activity for a specific period of time in public interest.

According to a press note, the ban on toys that look like “guns, pistols and Kalashnikovs” was a response to complaints by parents, after a surge in the sale of such toys before Eid.

Toy guns are a popular item in the bazars of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the Pashtun-dominated tribal areas, especially on the occasion of holidays such as Eid. Some psychologists, civil right activists, educationists and parents have been calling for a broader ban on toy guns in these areas, arguing that playing with such toys leads children towards violence and crime.

A number of studies show no link between playing with toy weapons in childhood and aggression in adulthood, and most adult men who did engage in gunplay as children do not commit violent crimes. But the activity may be seen as dangerous when combined with a number of other social, psychological and security-related factors in the local context of FATA and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

"It is not hard to divert children's attention to other toys"

Amid a growing demand for such items ahead of Eid, Shakir Khan, a shopkeeper in the Adenzai tehsil of Lower Dir told me he had bought a large number of toy weapons before Ramzan. “The wholesale dealers raise the prices of toy weapons closer to Eid,” he said.

There was a wide variety of toy guns in his shop, cost anywhere between Rs 20 and Rs 350. Most of his customers are not affluent, he told me. I also saw a small plastic dagger for Rs 10.

In the wholesale market in Batkhela, the headquarters of Malakand Agency from where he and other shopkeepers buy in bulk, there were toy guns as expensive as Rs 2,000. The largest toy stores are in Mingora city in Swat, which is also the headquarters of Malakand division.

“Toys are toys, whether they are guns, vehicles or helicopters. They’re all the same,” said Shakir Khan. He disagreed with the notion that playing with toy guns would make children violent or aggressive. “Children who play with toy buses and trucks do not grow up to become drivers or conductors.”

"Children who play with toy trucks don't become drivers"

But Muhammad Sajid, who runs a toyshop in the same area, does not sell toy guns and pistols. “Playing with guns promotes a violent culture,” he argued. “Sometimes children injure each other with plastic palettes too.”

According to Ahmad Ali, a wholesale dealer in Batkhela, toy weapons are the most popular item ahead of Eid. The pocket money, or Eidi, that children get on the day of the feast is spent on toys. Ahmad Ali said most boys prefer toy vehicles and toy guns, while most girls buy dolls and toy kitchenware. A large number of parents in rural areas are not even aware of the debate around the possible negative impacts of playing with toy guns, he said. “If they are banned, it would hurt the business and livelihoods of toyshop owners,” said Ahmad Ali.

“I think we should let the children decide whether they want to buy toy trucks or toy guns, or any other toys with their pocket money,” said Sheer Ghani, a father of three from Chakdara town. “It is the children who would play with those toys after all, and not us.”

But Muhammad Rahim, a parent from from Shergarh Mardan, said that he does not allow his children to buy toy guns. “If parents show some interest, it is not difficult to divert children’s attention from guns to other kind of toys,” he said.

Anas, a class-three student who lives in the Khadagzai village of Dir Lower, said all his cousins buy toy guns on Eid and play a gun battle game, often a police-versus-criminals roleplay. “We shoot at each other with plastic bullets.”

Burhan Marwat, an educationist from Sarai Naurang in Lakki Marwat, said it was his duty as a teacher to educate children about what kind of toys they should play with. “If parents are not aware of the harmful effects of toy guns, schools can play a role in discouraging such dangerous activities,” he said.

Hunar Koor, an organization promoting peace through skills-development, has been striving to end what it calls the “gun culture in Pashtun society”. The organization has carried out a number of campaigns in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the tribal areas to promote the use of educational toys. “Guns are not toys, they kill innocence. Instead of toy guns, children should be given toys that educate them,” said Amjad Shahzad, one of the founding activists at the organization.

Usman Ulasyar, chairman of the Suvastu Arts and Cultural Association, says such campaigns have educated a large number of parents about the negative impact of toy guns on their children. According to him, toy shops in Mingora city are much less likely to display toy guns and pistols than they were in the past.

A one-month ban under section 144 is not the solution, he says. “There should be legislation for a complete ban on the trade of toy guns.” Hunar Koor and Suvastu Arts and Cultural Association have jointly organized a number of seminars and awareness walks against weapons.

“Playing with toy guns in the militancy plagued Pashtun society appears to have a direct influence on violence and aggression,” according to Prof Dr Arabnaz Khan, chairman of the Department of Psychology at the University of Malakand.

“During the period of militancy in Malakand division, from 2007 to 2009, children developed new games while playing in the streets,” he said. “They shot at each other with toy guns, and made rocket launchers and mortar guns with empty beverage bottles, and grenades out of plastic bags filled with sand,” the professor said. “These games reflected what was happening around them. If the militancy had continued, children would have grown up and picked up real guns without hesitation.”

Toy gun battles would be harmless in a peaceful society where children have little access to real weapons, he said. “Even colorful toy guns would create problems in this part of the world. The only solution is to make them unavailable.”

Tahir Ali is a freelance reporter based in Islamabad