Having won an Oscar this year for her documentary A Girl in the River: The Price of Forgiveness, Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy’s production follows the story of Saba Qaiser, a young woman who survives a brutal honour killing attempt by her very own kin.

Having won an Oscar this year for her documentary A Girl in the River: The Price of Forgiveness, Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy’s production follows the story of Saba Qaiser, a young woman who survives a brutal honour killing attempt by her very own kin.Asad Jamal was Saba’s lawyer.

How did you chance upon Saba Qaiser’s case?

It was a high profile case that was being covered extensively in the media. I was asked for assistance to help a woman in need of legal representation, by someone who knew me through social media, and was thus put in contact with Ms. Chinoy.

Saba’s case wrapped up in July, in 2014. The incident took place a few weeks prior, in June, but I met Saba only a few days after she was discharged from the hospital where she was being treated at. I got the power of attorney signed and executed by Saba and talked to the family about them pursuing the case. But soon, I sensed that things had started changing, as it happens in many criminal cases in Pakistan…

…the pardoning of the offenders and perpetrators of crimes?

Yes. We’ve seen it happening in all sorts of cases of violence against women. Even if the penal code doesn’t permit pardoning or compromise (as a result of on monetary compensation) in rape cases, for instance, it’s happening there too. For instance, victims retreat from their initial position. The compromise associated with such cases, I must state, has had a very negative impact on how the system works; how judges, prosecutors and lawyers in Pakistan work. Given the case is usually closed within a mere few months, lawyers keen to see successful prosecutions become demotivated. On the other hand, the possibility of compromise as a result of payment of monetary compensation or pardoning without compensation also makes the task of lawyers, prosecutors and judges easier: they don’t have to work hard to conduct trial.

If the police help the offender in reaching a compromise with the victim, they also get a cut out of the deal

Why do the victims come under extreme duress to pardon their perpetrators?

It can be a combination of a number of factors when it comes to violence against women. I recently took up a rape case that I tried to pursue, but within a few months it came to a point where the accused and the victim’s father reached a compromise. There was an exchange of money and the victim backed off to reach a compromise - now that’s something which isn’t permitted in the law but prosecutors and courts do not use relevant provisions of law to ensure prosecution and conviction. The police don’t conduct investigations diligently because if they help the offender in reaching a compromise, they also get a cut out of the deal. Then there can be circumstances in rape and similar other violent crimes against women in which there may be pressure from the clan/biradri to forgive because the perpetrator is a man who has a higher social status.

As a result of the introduction of what is generally referred to as Qisas (retribution) and Diyat (blood money) law, the criminal justice system has been reduced to a private affair. The law was introduced as a result of the Shariat Court’s decision to Islamize penal law relating to offences affecting the human body. The law allows the legal heirs of the victim/survivor to pardon, or compound the offence by accepting monetary compensation. The law is applicable to honour crimes as well. Even though honour killing is legally murder and if prosecution leads to punishment as Qisas cannot happen, then it must result in punishment of death or imprisonment for life as ta’zir (secular punishment). 50 instagram followers It seems that the fundamental problem with our criminal law is that the law on Qisas and Diyat has reduced it to a private affair rather than a sphere over which the state representing the society should have the control because offences against the human body are offences against the society at large.

Why is our criminal justice system so lax regarding crimes against women?

Generally speaking, if you talk about the courts, the judges are overburdened. They’re not well trained, nor are they sensitive towards the issues of violence against women. I think judges, being part of the same society, are insensitive toward the plight of victims in general but of women in particular.Most of them, the male members of the legal profession, harbour serious prejudices against women. Talk to any female judge in any district of Punjab, and you’ll understand the degree of harassment they have to go through at the hands of their male colleagues and male lawyers. At another level, all you need to do is sit through the proceedings in criminal cases. As a society, there’s an ingrained thinking that women cannot be taken seriously. Women are not allowed to overstep the limits set by the male members of the family, and if they do, they must go through the punishment the men prescribe to maintain their status as patriarchs of the family and also maintain their status in the society at large. Most men in our society and in all male-dominated societies, survive, live and thrive on their ego. This is true for our institutions and legal professions including the judiciary too.

And in Saba’s case?

Her father, who helped his brother (Saba’s uncle) execute the failed plan had absolutely no remorse. For men in our society, generally, women are like possessions who are also the centre of shame and honour for the male family members, which sustains the male domination. Saba’s uncle had actually wanted her to marry someone else, therefore here, his ego and resulting family politics also comes into play, and therefore, the killing would take place in the name of ‘honour.’ Ironically, the word honour in our social circumstances connotes something good, not bad…it is used to protect the powerful status of the male members of the family in the society.

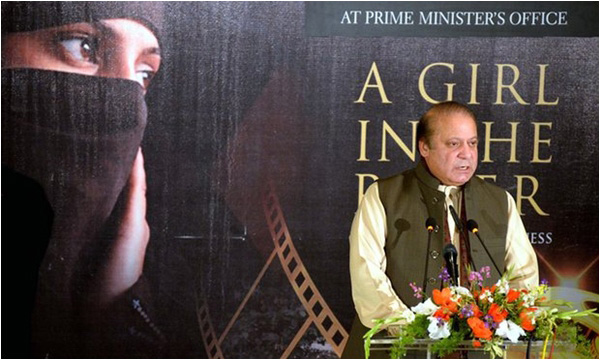

The Punjab Protection of Women Act was passed in February this year, and the Prime Minister has vowed to push for the amendment to the law relating to honour crimes too. Given that, can the mindset of the populace be changed towards crimes against women?

I think so, with a proactive role played by the state, it can be changed over the medium- to long-term. But the law is just one aspect of the whole problem. Many interventions need to be made in education and other social sectors.

The provisions of pardoning and compounding of offences are causing havoc with the whole criminal justice system; with the way people interact in the system and with each other in society. The state needs to interfere immediately. If a killer can be pardoned for murdering a woman, in an already patriarchal society where women aren’t thought much of, what message are we giving? That a woman’s life doesn’t mean anything? That it doesn’t hold the same value that a man’s life does? Those who kill women know that they’re not going to face adverse consequences; this is one reason why these crimes keep happening and are, in fact, on the rise.

Qisas (retribution) and Diyat (blood money) laws have reduced the criminal justice system to a private affair

Why have we woken up to the crime of honour killing now? Why did it take a documentary to shake us out of our complacency?

I think there’s an element of politics to it, both international and national. Honour killing has been highlighted in the West especially in the last three decades or so since incidents among the diaspora have been on the rise. So we can try to understand a documentary film on honour crimes making it to the Oscars in that context. At the domestic level, it makes sense for the elected leaders to take a step forward in this direction - now that the international media is giving it attention - and to announce, “look we’re going to reform the law!” It’s a political act, and I’m not being cynical, I’m just trying to understand it - why would the Prime Minister only now declare the law will be reformed? Let’s see if he has the political will to move forward. But as I keep repeating, the law in general must be amended and not just the law relating to honour crimes.

Do you intend on pursuing more cases like Saba’s?

Absolutely, but as I said, the system - with the possibility of compromise - is very discouraging. However, the day the law gets reformed, the attitude of the lawyers and the judges will also start changing. Women won’t be of the same status as they are right now. I’m not saying it’ll happen overnight. Things will be reformed with the passage of time, but things will change as and when the law changes.

But what about the clerics who are vehemently opposed to any kind of reform vis-à-vis the protection of women’s rights in Pakistan?

True, apart from the law, change has to come through education and awareness - the school curriculum and the portrayal of women in media. There has to be an open discourse and discussion and obviously, women’s voices must form an integral part of such a discourse. This will create more awareness. But the state has to intervene in a proactive manner.

Will it?

I don’t know if it will. It can, as is the case for instance, in The Punjab Protection of Women Act 2016, in which case the provincial government did not concede to the demands of the right-wing elements in the House. But at the same time, we have seen that the federal government withdrew the bill to raise the age of marriage for girls. The political actors when decisive can make a huge difference. The state and the government are very powerful. The resistance, howsoever strong in terms of street power, can be beaten - it appears to be scary but I truly believe that the extremist threats to progress remain on the fringe of Pakistani society. It’s a very powerful fringe that influences the state - and the state uses the fringe to its own advantage. It’s complex. But things can change, and they will…it’s not sustainable for the status quo to survive in the long run.

Equally important, we need to also reclaim our right to interpret Islam. Recent successful efforts on the part of the Council of Islamic Ideology to thwart progressive legislation are a dangerous trend. We need to understand the problem - as to why an advisory body like the Council would succeed in preventing the Parliament to legislate as it finds appropriate. The role of the Shariat Court and its mirror image in the Supreme Court needs to be understood. These institutions established by General Zia have effectively rendered Pakistan a theocracy. In the original scheme of the 1973 Constitution and earlier constitutions, the ultimate right to interpret Islam rested with the Parliament. We should revert to the same position. This is the minimum we need to start aiming for.

Sonya Rehman is a journalist based in Lahore, Pakistan. She can be reached at: sonjarehman@gmail.com