Data from initial reports of violence-related fatalities in Pakistan in 2015 paints a rosier picture than we have seen in years. Compared to 7,611 deaths in 2014, a total of 4,654 people died in 2015 as a direct result of violence, which is an average decrease of roughly 40%. This is even more impressive when you consider that year-over-year, 2014 had seen a 35% increase in fatalities over 2013, and that 2015’s figures are lower than those of 2013 as well.

A few conclusions can be drawn. First, the space for proscribed and terrorist groups is rapidly shrinking in the country. The Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) is reportedly beleaguered, in severe disarray and has had considerable difficulty finding any reliable footing in Pakistan. The leader of one of the most violent groups, Malik Ishaq, along with several followers were gunned down in a police encounter in July. The death of Ishaq, leader of the globally designated terror group Lashker-e-Jhangvi, marked a new turn for the security strategy in the country, but was answered brutally in the murder of Punjab’s Home Minister Shuja Khanzada, just over a month later.

On the other hand, several other groups and individuals have been allowed to operate unimpeded in the country. Oddly, Federal Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar stood on the floor of the parliament and asked the public to bring to light any evidence against the controversial firebrand cleric of the Red Mosque. This is a strange and unsettling departure from the security endeavors in the country, as cases have already been registered against the cleric, a non-bailable arrest warrant issued well over a year ago, and yet he roams the streets holding rallies to enforce Sharia Law, in open defiance of the state and its apparatus. Additionally, newer threats have also emerged, such as the group that targeted an Ismaili bus at Safoora Chowk in Karachi, killing dozens, as well as the ever-looming threat of Islamic State recruitment, financing and presence.

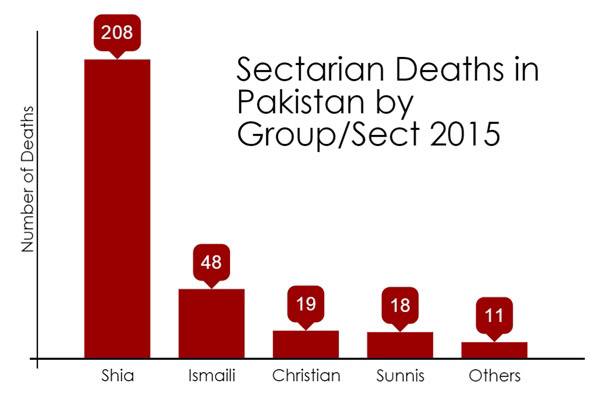

Additionally, Pakistan seems to be perpetually unable to protect the rights of its minorities, especially the Shia sect. Sectarian fatalities also saw a decline in 2015, with 272 fatalities, compared with 2014’s 420, which is a 35% decrease. However, the vast majority of these fatalities were Shia Pakistanis, who accounted for 208 of the 272 fatalities (76%).

This is especially alarming because despite a significant overall decrease in sectarian violence, Shias have seen a 10% increase in fatalities. Part of the reason for this is the historically weak state response to violence against minorities, and part of it is the impunity with which certain sectarian groups still operate within the country.

While the situation has improved overall, the urban pacification operation by the Rangers in Karachi and the Zarb-e-Azb by the military in the FATA belt is not a long-term sustainable solution. The military, while fierce in its enforcement of the state’s writ, cannot continue this momentum relentlessly. Ultimately it will fall to the civil law enforcement and security apparatus, including NACTA and IB, to curtail miscreants, criminals and terrorists in the long-run. Unfortunately, save a few examples, this objective seems largely neglected thus far.

The author is a journalist and a senior research fellow at the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad. He has a Master’s degree in strategic communications from Ithaca College, NY.

Email: zeeshan[dot]salahuddin[at]gmail.com

Twitter: @zeesalahuddin

A few conclusions can be drawn. First, the space for proscribed and terrorist groups is rapidly shrinking in the country. The Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) is reportedly beleaguered, in severe disarray and has had considerable difficulty finding any reliable footing in Pakistan. The leader of one of the most violent groups, Malik Ishaq, along with several followers were gunned down in a police encounter in July. The death of Ishaq, leader of the globally designated terror group Lashker-e-Jhangvi, marked a new turn for the security strategy in the country, but was answered brutally in the murder of Punjab’s Home Minister Shuja Khanzada, just over a month later.

On the other hand, several other groups and individuals have been allowed to operate unimpeded in the country. Oddly, Federal Interior Minister Chaudhry Nisar stood on the floor of the parliament and asked the public to bring to light any evidence against the controversial firebrand cleric of the Red Mosque. This is a strange and unsettling departure from the security endeavors in the country, as cases have already been registered against the cleric, a non-bailable arrest warrant issued well over a year ago, and yet he roams the streets holding rallies to enforce Sharia Law, in open defiance of the state and its apparatus. Additionally, newer threats have also emerged, such as the group that targeted an Ismaili bus at Safoora Chowk in Karachi, killing dozens, as well as the ever-looming threat of Islamic State recruitment, financing and presence.

Additionally, Pakistan seems to be perpetually unable to protect the rights of its minorities, especially the Shia sect. Sectarian fatalities also saw a decline in 2015, with 272 fatalities, compared with 2014’s 420, which is a 35% decrease. However, the vast majority of these fatalities were Shia Pakistanis, who accounted for 208 of the 272 fatalities (76%).

Newer threats have also emerged, such as the group that targeted Ismailis in the Safoora bus carnage

This is especially alarming because despite a significant overall decrease in sectarian violence, Shias have seen a 10% increase in fatalities. Part of the reason for this is the historically weak state response to violence against minorities, and part of it is the impunity with which certain sectarian groups still operate within the country.

While the situation has improved overall, the urban pacification operation by the Rangers in Karachi and the Zarb-e-Azb by the military in the FATA belt is not a long-term sustainable solution. The military, while fierce in its enforcement of the state’s writ, cannot continue this momentum relentlessly. Ultimately it will fall to the civil law enforcement and security apparatus, including NACTA and IB, to curtail miscreants, criminals and terrorists in the long-run. Unfortunately, save a few examples, this objective seems largely neglected thus far.

The author is a journalist and a senior research fellow at the Center for Research and Security Studies, Islamabad. He has a Master’s degree in strategic communications from Ithaca College, NY.

Email: zeeshan[dot]salahuddin[at]gmail.com

Twitter: @zeesalahuddin