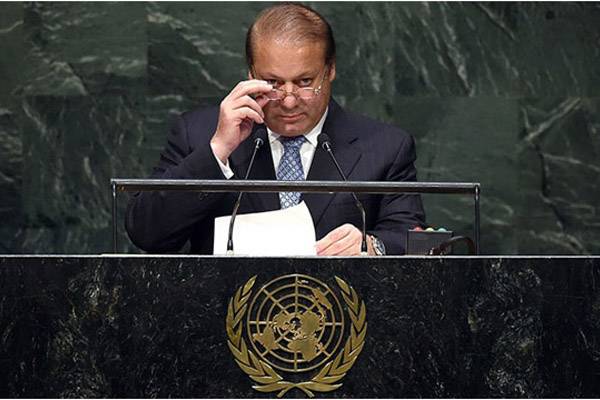

Much has been written about this year’s India-Pakistani row at the United Nations General Assembly. Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif raised Islamabad’s pitch over Kashmir, not only seeking UN attention to resolve the dispute but also shooting off a four-point formula to make peace with India. On its part, India maintained cool. In fact, it chose to largely ignore Sharif’s offer.

The Pakistani prime minister did receive appreciation for his “bold” stance vis-a-vis Kashmir at the UN, but the fact that most of the analysts ignore is that India was cautious about how Pakistan would behave at the UN this year. It was well understood that in the wake of the cancellation of talks between the national security advisers of the two countries in August this year – for which a major part of the blame fell on India – Sharif would be a hardliner at the podium. He had no other choice. When the talks had to be called off following a rather “untenable” condition that New Delhi had put, Sharif came under tremendous pressure to say no. India’s condition – that the Pakistani delegation would not meet Kashmiri leaders from the Hurriyat Conference – became a stronger bone of contention between the two countries than the Kashmir dispute itself. Two days before that, Pakistan had unilaterally called off a Commonwealth Conference after India raised an objection that its Jammu and Kashmir Assembly’s speaker had not been invited.

When the talks came to a naught, Nawaz Sharif was in fact paying the debt to a strong Kashmir constituency in Pakistan, which had taken offence over the omission of Kashmir in a statement issued after a meeting at the sidelines of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit in Ufa. He had earlier been “taken to task” by the hardliners for accepting Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s invitation to his swearing in ceremony in New Delhi. That was followed by the cancellation of talks between the foreign secretaries of the two countries in 2014, on the same grounds – that Pakistan must not hold any discussions with Hurriyat leaders prior to the talks.

This time when Sharif was addressing the UN, something different was happening on the Indian side. Modi, who was also in the United States wooing global businesses to invest in India, chose not to attend the UN General Assembly session himself. Instead, his Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj addressed the gathering. This was perhaps a calculated move to deny importance to Sharif’s expected speech at the UN. The response to his or Sartaj Aziz’s speech was reduced to the level of the first secretary at India’s UN mission, who exercised the right to reply.

But that does not make Sharif and his speech irrelevant. It was after a long time that Pakistan devoted so much time in the UN to India and particularly Kashmir. But it needs to be seen in the backdrop of heightened tension between the two countries in the last year. Nawaz was left with no choice but to raise the issue in this manner. In case New Delhi and Islamabad had moved ahead on the proposed mutual roadmap as envisaged in the Ufa joint statement, and if the borders had not witnessed bloody skirmishes, the ambiance in New York would have surely been different.

When Pakistan initiated a peace process with India through the podium of the United Nations General Assembly on November 24, 2003, it had been caught in a dilemma. It was a non-permanent member in the Security Council, and chose not to make things tough for New Delhi.

“India was unmistakably worried that Pakistan might introduce some new initiatives on Kashmir, particularly during our presidency in May 2003,” former Pakistan foreign minister Khurshid Mahmud Kasuri writes in his book ‘Neither a Hawk nor a Dove’. He details how Islamabad deliberated on the issue in the backdrop of waning support from the international community in the wake of 9/11.

Quoting an intense meeting with seasoned Pakistani diplomats, Kasuri writes: “This meeting further confirmed my belief that the national interests of Pakistan and the interests of the people of Jammu and Kashmir demanded a serious bilateral dialogue with India over this dispute, as that was the only way to achieve a solution reflective of the aspirations of Kashmiris who have suffered for decades under the Indian occupation.”

Having said that, the fact remains that UN resolutions provided a legal and moral authority to Islamabad’s calls to resolve the dispute of Jammu and Kashmir. A response by then-Governor General of India Lord Mountbatten to the UN, on behalf of the Indian cabinet, clearly states that the matter of the accession should be referred to the people of Jammu and Kashmir. These resolutions are a strong base for finding a solution to the dispute, and that is what Pakistan has been saying all along, in and outside the UN.

When Sharif presented his four-point formula to ease tensions with India, he forgot that he took refuge under what his bête noire Pervez Musharraf had done in 2003. The four points are as follows:

1) Pakistan and India should formalize and respect the 2003 understanding for a complete ceasefire on the Line of Control in Kashmir, and for this purpose, the UNMOGIP should be expanded to monitor the ceasefire,

2) Pakistan and India should reaffirm that they will not resort to the use or the threat of use of force under any circumstances (This is a central element of the UN Charter)

3) Steps should be taken to demilitarize Kashmir, and

4) There should be an unconditional mutual withdrawal from Siachen Glacier, the world’s highest battleground.

To some extent, Nawaz Sharif managed to corner India. A call for peace in the United Nations cannot go unheard. He has put the onus on New Delhi once again. But one thing is clear: unlike the impression being given by the pro-Kashmir constituency in Pakistan or the resistance groups in Kashmir itself, it was not an extraordinary situation.

Sooner or later, the dispute has to be resolved, and the road to that process goes through New Delhi and Islamabad, before it reaches Kashmir. UN or no UN, Kashmir is a wound that needs healing. Neither India nor Pakistan can run away from that reality.

The Pakistani prime minister did receive appreciation for his “bold” stance vis-a-vis Kashmir at the UN, but the fact that most of the analysts ignore is that India was cautious about how Pakistan would behave at the UN this year. It was well understood that in the wake of the cancellation of talks between the national security advisers of the two countries in August this year – for which a major part of the blame fell on India – Sharif would be a hardliner at the podium. He had no other choice. When the talks had to be called off following a rather “untenable” condition that New Delhi had put, Sharif came under tremendous pressure to say no. India’s condition – that the Pakistani delegation would not meet Kashmiri leaders from the Hurriyat Conference – became a stronger bone of contention between the two countries than the Kashmir dispute itself. Two days before that, Pakistan had unilaterally called off a Commonwealth Conference after India raised an objection that its Jammu and Kashmir Assembly’s speaker had not been invited.

When the talks came to a naught, Nawaz Sharif was in fact paying the debt to a strong Kashmir constituency in Pakistan, which had taken offence over the omission of Kashmir in a statement issued after a meeting at the sidelines of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit in Ufa. He had earlier been “taken to task” by the hardliners for accepting Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s invitation to his swearing in ceremony in New Delhi. That was followed by the cancellation of talks between the foreign secretaries of the two countries in 2014, on the same grounds – that Pakistan must not hold any discussions with Hurriyat leaders prior to the talks.

The meeting with Kashmiri leaders became a bigger dispute than Kashmir itself

This time when Sharif was addressing the UN, something different was happening on the Indian side. Modi, who was also in the United States wooing global businesses to invest in India, chose not to attend the UN General Assembly session himself. Instead, his Foreign Minister Sushma Swaraj addressed the gathering. This was perhaps a calculated move to deny importance to Sharif’s expected speech at the UN. The response to his or Sartaj Aziz’s speech was reduced to the level of the first secretary at India’s UN mission, who exercised the right to reply.

But that does not make Sharif and his speech irrelevant. It was after a long time that Pakistan devoted so much time in the UN to India and particularly Kashmir. But it needs to be seen in the backdrop of heightened tension between the two countries in the last year. Nawaz was left with no choice but to raise the issue in this manner. In case New Delhi and Islamabad had moved ahead on the proposed mutual roadmap as envisaged in the Ufa joint statement, and if the borders had not witnessed bloody skirmishes, the ambiance in New York would have surely been different.

When Pakistan initiated a peace process with India through the podium of the United Nations General Assembly on November 24, 2003, it had been caught in a dilemma. It was a non-permanent member in the Security Council, and chose not to make things tough for New Delhi.

“India was unmistakably worried that Pakistan might introduce some new initiatives on Kashmir, particularly during our presidency in May 2003,” former Pakistan foreign minister Khurshid Mahmud Kasuri writes in his book ‘Neither a Hawk nor a Dove’. He details how Islamabad deliberated on the issue in the backdrop of waning support from the international community in the wake of 9/11.

Quoting an intense meeting with seasoned Pakistani diplomats, Kasuri writes: “This meeting further confirmed my belief that the national interests of Pakistan and the interests of the people of Jammu and Kashmir demanded a serious bilateral dialogue with India over this dispute, as that was the only way to achieve a solution reflective of the aspirations of Kashmiris who have suffered for decades under the Indian occupation.”

Having said that, the fact remains that UN resolutions provided a legal and moral authority to Islamabad’s calls to resolve the dispute of Jammu and Kashmir. A response by then-Governor General of India Lord Mountbatten to the UN, on behalf of the Indian cabinet, clearly states that the matter of the accession should be referred to the people of Jammu and Kashmir. These resolutions are a strong base for finding a solution to the dispute, and that is what Pakistan has been saying all along, in and outside the UN.

When Sharif presented his four-point formula to ease tensions with India, he forgot that he took refuge under what his bête noire Pervez Musharraf had done in 2003. The four points are as follows:

1) Pakistan and India should formalize and respect the 2003 understanding for a complete ceasefire on the Line of Control in Kashmir, and for this purpose, the UNMOGIP should be expanded to monitor the ceasefire,

2) Pakistan and India should reaffirm that they will not resort to the use or the threat of use of force under any circumstances (This is a central element of the UN Charter)

3) Steps should be taken to demilitarize Kashmir, and

4) There should be an unconditional mutual withdrawal from Siachen Glacier, the world’s highest battleground.

To some extent, Nawaz Sharif managed to corner India. A call for peace in the United Nations cannot go unheard. He has put the onus on New Delhi once again. But one thing is clear: unlike the impression being given by the pro-Kashmir constituency in Pakistan or the resistance groups in Kashmir itself, it was not an extraordinary situation.

Sooner or later, the dispute has to be resolved, and the road to that process goes through New Delhi and Islamabad, before it reaches Kashmir. UN or no UN, Kashmir is a wound that needs healing. Neither India nor Pakistan can run away from that reality.