Yasmin Khan

Vintage London and Random Gurgaon, 2015

Seventy years have passed since the end of the Second World War – arguably the most devastating war in human history. Even as different countries commemorate the event and remember the near 60 million people who died either in battle or attacks on civilians or genocide – or simply because the related costs of war were too high – the world has not learned its lesson. Hobbes was correct: wars have become a ‘normal’ feature of international affairs. And yet, since antiquity, large-scale wars have brought with them devastation for the many, but also prosperity for the few. The Second World War was no aberration in this sense: it allowed many to profit and prosper. In her book, The Raj at War, historian Yasmin Khan discusses both aspects with her characteristic erudition and gives one powerful reason to believe that the Second World War was won by the colonies for the colonizers.

Quite apart from the War, India was grappling with its own political problems during this period: the Quit India Movement was launched in 1942, the Hindu-Muslim divide had widened, the demand for Pakistan was gaining strength under the Muslim League, and the Indian National Army, led by Subhash Chandra Bose, had joined hands with the axis powers to fight against the British for India’s independence. While these parallel developments had influenced or been influenced by the ongoing war, they did not have a significant impact on military operations per se. There were too many opposing vested interests: both the political leadership in India and the Indian public itself was divided over whether or not to support the war effort.

There is reason to argue that the Second World War was won by the colonies for the colonizers

Khan explores numerous instances of wartime opportunism in India, especially among the nobility and mercantile class. Anticipating either wartime or postwar gains, many Indians chose to support the British Crown. The Maharaja of Jammu, for instance, offered the use of two infantry battalions and one mountain battery for deployment anywhere in the world. The princely state would pay for these men and support their families while they were away from home. The Maharaja also invited recruiting parties to Kashmir.

Jodhpur and Bikaner made similar offers of troops and money. Indore donated 500,000 rupees, Travancore 600,000 rupees, and Bikaner 150,000 rupees. The Nizam of Hyderabad set aside over 100,000 pounds for the Air Ministry, and Maharaja Jam Sahib of Nawanagar vowed to contribute a tenth of the gross revenues of his state to the war effort. In India’s business community was the pre-eminent industrialist Ghyanshyam Das Birla, whose factories boomed with wartime contracts.

There is reason to argue that the Second World War was won by the colonies for the colonizers

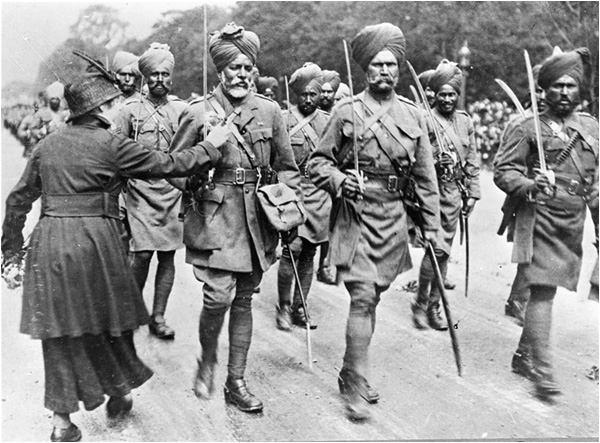

Ordinary people ‘benefitted’ in certain ways too. Following the 1857 Mutiny, the British had divided Indian castes into what they termed ‘martial’ and ‘non-martial’ races. The former had helped suppress the rebellion and were encouraged to join the British army. For these men, being a soldier accorded them a special ‘status’. It became a matter of pride and many joined the British Indian army during the War out of a sense of honour. But others chose to join up because it provided them a regular salary to support their families. The army also became a safe house of sorts for those who had left home for social or personal reasons. All of them fought for the Empire without understanding the real motives of the War. After serving in various parts of the world, understanding what had led to the War and being influenced by the ongoing Indian freedom movement, some soldiers resisted against the prevailing discrimination in the British military. At the fag end of British rule, many soldiers mutinied against their masters.

The War gave rise to numerous ‘opportunities’ for other groups who needed to earn a living even if it meant physical exploitation for some economic gain, however paltry. Sex workers and daily wage labourers found fresh demand for their services. Brothels flourished near the British cantonments, meeting soldiers’ sexual needs and serving as a means of livelihood for many women – some who had been lured into the profession and others who had entered it out of acute poverty. Invariably, the incidence of venereal disease increased. The War also provided menial jobs to daily wage earners who were paid very little, but just enough to keep their families fed. Khan points out that labour was cheap enough even for the average American GI to employ a domestic servant.

But where there were jobs to be had, Khan reminds us that there was also unprecedented devastation, large-scale suffering and civilian deaths. As wartime requirements for troops escalated, many young men were forcibly recruited into the British Indian army. Once the traditional recruiting areas had been drained, agents moved into other areas, lowering the standard height and age criteria for enlistment. In many villages, not a single young man was to be seen: all of them had been recruited to meet the needs of the War. In Nepali folklore, the word dukha (sadness) was used to describe the despair of those women whose fathers, brothers and sons had been lost to the War, leaving them with mouths to feed and farmland to plough. For new recruits, the casualty rate was often much higher because many of them were sent into battle with just the bare bones of training.

During the War, eastern India suffered one of its worst famines, which led to the death of millions. It was not that there wasn’t enough food – it was that the supply mechanism had virtually broken down. The wartime administration’s priority was to meet the military’s demand for food, even at the cost of letting common people starve. As the War advanced towards the borders of British India, thousands were left stranded in war zones in Burma. The British evacuated whom they could, but as Khan argues, they invariably gave priority to British citizens and upper-class Indians.

Yasmin Khan’s rigorous investigation of the less well-documented aspects of the Second World War make her latest book an invaluable addition to the existing literature on the subject.