Suchetana Chattopadhyay

New Delhi: Tulika Books, 2012

The historiography of the freedom movement of India has been dominated by the rivalry between the Indian National Congress (INC) claiming to represent all Indians – irrespective of caste, creed or colour and to the establishment of a secular democratic state – and the All India Muslim League (AIML), claiming to be the sole representative of Indian Muslims and demanding the partition of India for a Muslim homeland where it could build a nation based on Muslim culture and values. However, the INC and AIML were not the only parties whose role during the freedom struggle needs to be evaluated in order to capture the full range of opinions that emerged in the twentieth century as to the future of India without a colonial power. There were extremist Hindu parties that wanted India either to be partitioned so that the Muslims might be excluded from building a ‘homogeneous’ grand Hindu rashtra or reduced to second-rate citizens within an India unequivocally privileging Hindus over Muslims and other minorities.

On the other hand, there were Muslims all over India who were opposed to the country’s division and remained so until Partition become a fait accompli. They either joined the INC or became its allies. There was yet another group of people, consisting of Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and others, who were committed not only to the political liberation of India, but also to a social liberation of the oppressed so that political emancipation could be combined with a deep social transformation that would end class exploitation and its concomitant social and cultural practices. They were the harbingers of the Communist movement in the Subcontinent and Indian Muslims were among its pioneers. In fact, Muslim representation at the highest level of leadership nearly matched that of other communities involved in the Communist movement.

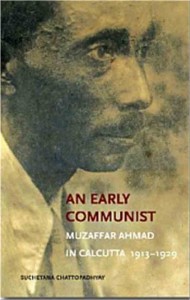

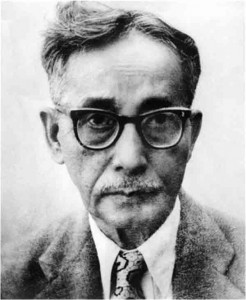

Who were these Muslims? What was their social and political background? Dr Suchetana Chattopadhyay’s book An Early Communist: Muzaffar Ahmad in Calcutta 1913–1929 provides clues in an impressive study of one these pioneers, Muzaffar Ahmad (1889–1973). Although the study covers only his formative period and activism, Ahmad’s commitment to Communism remained steadfast till his death in Calcutta in 1973. At that time, he was a leading light of the Communist Party of India (Marxist).

The level of Muslim leadership nearly matched that of other communities in the Communist movement

The author undertakes a detailed and nuanced contextualization of Muslim radicalism, drawing on international as well as Indian – and particularly Bengali – contexts. Internationally, the European powers dominated world politics: Asia and Africa were, by and large, colonies of these powers. At the all-India level, the British played the masterstroke of granting separate electorates in 1909, effectively pre-empting the Hindus and Muslims from joining ranks against them. In the immediate term, severe upheavals caused by the partition of Bengal in 1905, and later its annulment in 1911, had resulted in the rise of terrorism, Hindu revivalism and Muslim separatism. Upper-caste Hindu Bhadraloks (Barre Log) began to spearheaded Bengali nationalism laced with Hindu revivalist ideas and symbolism. The extreme wing of such nationalism was attracted to terrorism. In contrast, the smaller Muslim elite and intelligentsia of Bengal, which included Urdu-speaking families settled in Bengal, either supported the loyalist AIML or were attracted to pan-Islamism.

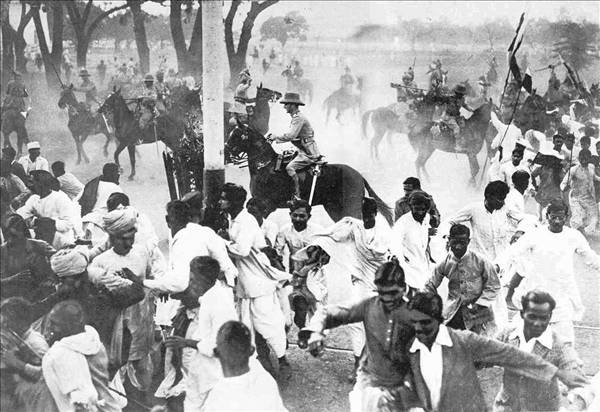

Muzaffar Ahmad was born into a lower middle-class but moderately educated family on an island off Chittagong in the Bay of Bengal. Wanting to educate himself and escape the parochialism of a small island, he migrated to Calcutta in 1913 – then the hub of industrial and commercial activity (Bombay had not as yet taken over the leading role). Moreover, despite the colonial capital shifting to Delhi in 1911, Calcutta remained the leading centre of Indian political activism of all varieties. It represented a typical colonial topography. The best localities were, naturally, inhabited by the Europeans. There were, of course, residential quarters of affluent Hindus and Muslims separated from one another. Impoverished but struggling sections of the lower middle class and working class Hindus and Muslims lived in rundown areas. Plague, malaria, cholera, typhoid, dengue and other such diseases ravaged the lives of the unfortunate. Crime was rampant, while communal tension and class conflict kept the city volatile. From time to time, people agitated against their harsh conditions, only to face severe repression at the hands of the colonial authorities and their native subordinates.

Ahmad had no family in Calcutta. He tried hard to get a proper university education, but failed. Such trials did not deter him. He read a great deal, took part in intellectual discussions and took up journalistic and editorial assignments. Muslim students like him faced considerable difficulty in renting rooms owned by Hindus. There was, however, some networking between Hindus and Muslims as unemployment and other difficulties compelled them to think and act beyond the narrow pale of religious orthodoxies. It was a time when the Muslim intelligentsia felt frustrated not only by their adverse socioeconomic circumstances, but also by the general defeat and despondence of the Muslim world. The last symbol of Muslim power, the Ottoman Empire, was beset with irreversible decline. Revolts in Eastern Europe had already resulted in successful secessions and the shrinking of Ottoman territories.

Under the circumstances, political Islam, in the form of pan-Islamism, profoundly influenced individuals such as Muzaffar Ahmad, whose imagination was initially captured by the Khilafat movement. This is important to note because the trend arose all across the Subcontinent’s Muslims. We, in the Punjab, who have been associated with the Left movement, are aware of the fact that a number of anti-colonial and anti-imperialist Punjabi Muslims – Khilafatists and Hijratites – were radicalized by the harsh treatment that Ottoman Turkey received at the hands of the Allies, especially Britain.

If I am not mistaken, Comrade Fazal Elahi Qurban and possibly Dada Ferozuddin Mansur, among others, left the Subcontinent in hopes of establishing a revolutionary government-in-exile in Afghanistan. They eventually arrived in Central Asia where the zeal unleashed by the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution deeply impressed them. Some went to Moscow and even met the Bolshevik leaders. The earliest pioneers of Communist ideas and anti-colonial movements in the Indian Subcontinent were these returnees from the Soviet Union. In this regard, the Ghadar Party also played an important role in creating networks among the Hindu, Muslim and Sikh revolutionaries of those days. However, at the other end of the Subcontinent, in Bengal, Muzaffar Ahmad, Abdul Halim and some others were originally volunteers to the Khilafat Movement, although they were not part of the Russia-returned group of Muslim revolutionaries.

A return to the Vedic age or to the Khilafat-e-Rashada era was not a rational or realistic option

Chattopadhyay’s book covers key historical events in Muzaffar Ahmad’s life, from the eve of World War I to the notorious Wall Street stock market crash, resulting in the Great Depression of 1929. During this period, the world economy took a great hit: the prices of food items and other essential commodities skyrocketed, productive units closed down and unemployment hit cultivators, artisans and industrial workers. No other city experienced greater social misery and despair than Calcutta. Muslim men and women were a sizeable section of the working class. They joined ranks with workers from other religious communities and castes. Such solidarity began to impress individuals like Ahmad. Strikes and demonstrations were met with severe repression by the colonial authorities; this resulted in efforts to unionize and build solidarity among the abject poor.

It was in such a volatile and explosive atmosphere that radicalized Muslims such as Ahmad were attracted to socialism. We learn that the renowned poet Qazi Nazrul Islam was in the same group of Muslim Bengalis who began to look upon the Bolshevik Revolution as their inspiration for a new world order based on the end of exploitation of man by man and nation by nation. In any event, it was a Hindu, Bhadralok Makhanlal Gangopadhyay, who introduced Ahmad to socialist literature in 1921. Thereafter, he read the Marxist classics as well as anti-Communist socialist literature. It was the Communist version that appealed to him most and he also made contact with the roving maverick of socialism, fellow Bengali N. M. Roy. The Communist International floated by the Soviet Union, the Comintern, also linked up with the Indian Communists, and Marxism-Leninism found a firm foothold in Bengal.

In 1922, Ahmad was arrested and sentenced to prison for six months for writing an anti-colonial editorial. The police and other intelligence agencies had been monitoring him closely. Thus, when the authorities learned that he was likely to attend a conference of the All-India Trade Union Congress in Lahore, they decided it would be “worthwhile to warn Lahore police to watch over him and someone who knows him should shadow him up to Lahore”. Hafiz Masud Ahmad, a police informer, was assigned the duty of shadowing Ahmad. Another agent who kept an eye on the Bengali Communists was Sisirkumar Ghosh. Thus began a number of prison sentences for allegedly taking part in activities meant to threaten colonial rule.

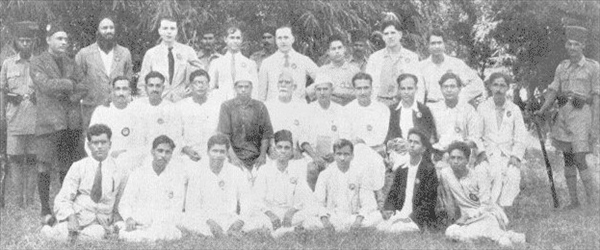

It was, however, the Kanpur Communist Conference – which Ahmad attended after his release from prison – that set in motion the establishment of a network of Communists all over India. The Kanpur Conspiracy Case was launched against these pioneers: M. N. Roy (in absentia), Muzaffar Ahmad, S. A. Dange, Shaukat Usmani, Nalini Gupta, Singaravelu Chettiar, Ghulam Hussain and others were caught by the Government and charged with conspiring to “deprive” the King Emperor of his sovereignty over British India. Hussain turned informer and was pardoned. Ahmad and the others were sent to jail for four years.

The trial had the opposite effect the authorities might have hoped for. The newspapers covered the matter exhaustively and the public learned about the Communist doctrine for the first time. The headquarters of the Communist Party of India (CPI) was established in Bombay and then shifted to Delhi; metropolitan branches in Lahore, Kanpur, Madras and Calcutta also came into being. Contact between the Indian and international Communist movements was mediated through workers in London, Paris, Berlin and Moscow. Foreign (especially British) Communists started arriving in India around 1925. Such visits were often cut short through deportations, arrests and imprisonments.

While adhering to Lenin’s call to work with the nationalists, the CPI was critical of the limited demands for self-government, which INC had been advocating. Ahmad also spearheaded the socialist press in Bengal. He and other Muslim Communists prepared a telling critique of the shuddi Sangathan movements of Hindu revivalism and their opposing Muslim responses of tanzeem and tabliq. They argued that a return to the Vedic age or to the Khilafat-e-Rashada era was not a rational or realistic option since these idealized and romanticized depictions of a mythical past represented outmoded ideas and institutions.

Meanwhile, the British government struck a second time. The so-called Meerut Conspiracy Case was initiated in 1929. The main charges were that, in 1921, Dange, Shaukat Usmani and Muzaffar Ahmad had entered into a conspiracy to establish a branch of the Comintern in India, helped by various persons, including Phillip Spratt and Benjamin Francis Bradley (sent to India by the Communist International). The aim of the accused, according to the charges raised against them was: “to deprive the King Emperor of the sovereignty of British India, and for such purpose to use the methods and carry out the programme and plan of campaign outlined and ordained by the Communist International.”

The Sessions Court in Meerut handed down stringent sentences to the accused in January 1933. More than two-dozen persons were convicted with various durations of “transportation”. While Ahmed was transported for life, Dange, Spratt, Ghate, Joglekar and Nimbkar were each awarded transportation for a period of 12 years. On appeal, in August 1933, the sentences of Ahmad, Dange and Usmani were reduced to three years by Sir Shah Sulaiman, Chief Justice of the Allahabad High Court.

In a concluding chapter, we learn that Ahmad remained active in Communist politics. At the time of Partition in 1947, he remained in Calcutta and later sided with those Communists who were critical of the Soviet Union and founded the CPI-M. For all those interested in understanding the origins of the Communist movement in India, Chattopadhyay’s book is a must-read.