In Dir, one of the most socially conservative regions of Pakistan, politics is a men-only affair. Women are often not even allowed to vote.

There have been 10 general elections in the area since the princely state of Dir merged into Pakistan in 1969, but women were never allowed to actively participate in politics. Things were no different in the local government elections.

“Illiteracy, sociocultural and religious challenges, ignorance by their male counterparts, and above all an unfavorable polling station environment hinder their participation in the decision-making process,” said Shaad Begum, a social worker from Lower Dir.

In the parliamentary by-elections earlier in May, of a total of 5,300 registered women voters, not a single female cast her vote. The PK-95 seat had fallen vacant after Jamaat-e-Islami emir Sirajul Haq was elected senator. Azazul Mulk Afkari of JI had won the elections. But the men-only turnout sparked a nationwide controversy. The Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) declared the polls void because of the disenfranchisement of women, but the Peshawar High Court stayed the decision on June 12 in response to a petition filed by Azazul Mulk.

“We have been disappointed by the decision of the court,” said Shaad Begum, who also criticized the ECP for holding elections in joint polling stations for men and women in Dir. “There were no separate polling stations for women. How can a woman vote in a joint polling station?” she said. “The preparations made by the government and the ECP were neither culture sensitive nor gender sensitive.”

The political leadership, elders and even the religious figures in the area publicly talk about women’s empowerment and admit that female voters should be part of the political system. But the ground realty is different.

According to Shaad Begum, the people of Dir never genuinely wanted to empower women. “It was not only the Taliban who opposed women’s empowerment. Ordinary citizens, local jirgas, the political leadership and religious leaders in the area have always discouraged women’s education, jobs, politics and mobility,” she said.

Aisha, 33, a resident of Jandul in Dir, is of the view that women should actively take part in elections. “Only a female candidate can understand the problems of women,” she says, “so the government should make proper arrangements to ensure female participation in the elections and other decision-making processes.”

She believes no one would object to women voting in the elections if there were separate polling stations for them. “Even in Peshawar and Punjab, women cast their votes in separate polling stations.”

Not all local women agree with her views. “We are dependent on our men when it comes to income,” says Sultan Bibi, 63. She has never voted in an election. “We don’t know what is going on outside our houses, so there is nothing wrong with it if our men decide the fate of our area.”

Azazul Mulk says women do not vote because of cultural constraints and low literacy. “There are no restrictions on women, but men don’t show interest in taking their womenfolk with them for voting,” he said. “The people of the area support women’s participation in the electoral process, but the government and the ECP set up separate polling stations for them.”

Background interviews show that a majority of men in Dir do not want women to leave their homes, especially to places where there are other men. In Peshawar and Mardan, where women participate in the elections, female relatives of the contesting candidates take part in door-to-door campaigns. But political leaders in Dir, regardless of whether they represent liberal or religious political parties, don’t allow that.

“My traditions and my tribal background don’t allow the women of my family to visit the houses of people who work in our fields as farmers,” said a politician and chieftain who represents a secular party in Dir.

In the recent local elections, influential political leaders fielded ‘puppet candidates’ on the seats reserved for women – the wives of barbers, blacksmiths and agricultural laborers who worked for them. In some cases, locals say the women did not even know what they were doing with their identity card, or even that they had won the elections. Their only utility, they say, is to vote for the men in the elections for nazim.

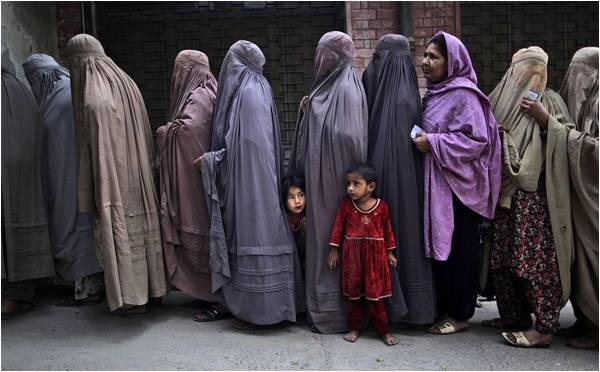

An overwhelming majority of women in Dir observe a strict form of purdah. They are not allowed to leave their houses during the day even if they cover their faces. They visit their relatives at night. They wear blue burkas and cannot be identified. Some locals say that may create a security concern even if separate polling stations were set up for women.

Jamaat-e-Islami is the only party in Dir that has trained and educated female political workers. If separate polling stations for women are established, some parties fear their female workers will not be able to compete with them. “No party can compete with the JI in this regard,” according to a local leader of Pakistan People’s Party. “Allowing female participation in the elections means making the JI invincible in Dir.”

Professor Abasin Yousafzai, a Pashtun writer and poet who belongs to Dir says it is “an extreme form of hypocrisy”.

“All the politicians in Dir claim to support women’s role in politics and talk about women’s empowerment, but when it comes to their own women, they don’t allow them any such rights,” he says.

In the past, politicians and religious leaders have made verbal agreements at jirgas that women will not be allowed to vote. Sometimes, announcements were made in mosques about a ban on voting for women.

A small number of women did vote in Timargarah and Chakdara towns of Lower Dir during the recent local elections. Civil rights activists termed as the “worst form of tokenism”.

Tahir Ali is an Islamabad-based journalist

Twitter: @tahirafghan

There have been 10 general elections in the area since the princely state of Dir merged into Pakistan in 1969, but women were never allowed to actively participate in politics. Things were no different in the local government elections.

“Illiteracy, sociocultural and religious challenges, ignorance by their male counterparts, and above all an unfavorable polling station environment hinder their participation in the decision-making process,” said Shaad Begum, a social worker from Lower Dir.

In the parliamentary by-elections earlier in May, of a total of 5,300 registered women voters, not a single female cast her vote. The PK-95 seat had fallen vacant after Jamaat-e-Islami emir Sirajul Haq was elected senator. Azazul Mulk Afkari of JI had won the elections. But the men-only turnout sparked a nationwide controversy. The Election Commission of Pakistan (ECP) declared the polls void because of the disenfranchisement of women, but the Peshawar High Court stayed the decision on June 12 in response to a petition filed by Azazul Mulk.

"There were no separate polling stations for women"

“We have been disappointed by the decision of the court,” said Shaad Begum, who also criticized the ECP for holding elections in joint polling stations for men and women in Dir. “There were no separate polling stations for women. How can a woman vote in a joint polling station?” she said. “The preparations made by the government and the ECP were neither culture sensitive nor gender sensitive.”

The political leadership, elders and even the religious figures in the area publicly talk about women’s empowerment and admit that female voters should be part of the political system. But the ground realty is different.

According to Shaad Begum, the people of Dir never genuinely wanted to empower women. “It was not only the Taliban who opposed women’s empowerment. Ordinary citizens, local jirgas, the political leadership and religious leaders in the area have always discouraged women’s education, jobs, politics and mobility,” she said.

Aisha, 33, a resident of Jandul in Dir, is of the view that women should actively take part in elections. “Only a female candidate can understand the problems of women,” she says, “so the government should make proper arrangements to ensure female participation in the elections and other decision-making processes.”

She believes no one would object to women voting in the elections if there were separate polling stations for them. “Even in Peshawar and Punjab, women cast their votes in separate polling stations.”

Not all local women agree with her views. “We are dependent on our men when it comes to income,” says Sultan Bibi, 63. She has never voted in an election. “We don’t know what is going on outside our houses, so there is nothing wrong with it if our men decide the fate of our area.”

Azazul Mulk says women do not vote because of cultural constraints and low literacy. “There are no restrictions on women, but men don’t show interest in taking their womenfolk with them for voting,” he said. “The people of the area support women’s participation in the electoral process, but the government and the ECP set up separate polling stations for them.”

Background interviews show that a majority of men in Dir do not want women to leave their homes, especially to places where there are other men. In Peshawar and Mardan, where women participate in the elections, female relatives of the contesting candidates take part in door-to-door campaigns. But political leaders in Dir, regardless of whether they represent liberal or religious political parties, don’t allow that.

“My traditions and my tribal background don’t allow the women of my family to visit the houses of people who work in our fields as farmers,” said a politician and chieftain who represents a secular party in Dir.

In the recent local elections, influential political leaders fielded ‘puppet candidates’ on the seats reserved for women – the wives of barbers, blacksmiths and agricultural laborers who worked for them. In some cases, locals say the women did not even know what they were doing with their identity card, or even that they had won the elections. Their only utility, they say, is to vote for the men in the elections for nazim.

An overwhelming majority of women in Dir observe a strict form of purdah. They are not allowed to leave their houses during the day even if they cover their faces. They visit their relatives at night. They wear blue burkas and cannot be identified. Some locals say that may create a security concern even if separate polling stations were set up for women.

Jamaat-e-Islami is the only party in Dir that has trained and educated female political workers. If separate polling stations for women are established, some parties fear their female workers will not be able to compete with them. “No party can compete with the JI in this regard,” according to a local leader of Pakistan People’s Party. “Allowing female participation in the elections means making the JI invincible in Dir.”

Professor Abasin Yousafzai, a Pashtun writer and poet who belongs to Dir says it is “an extreme form of hypocrisy”.

“All the politicians in Dir claim to support women’s role in politics and talk about women’s empowerment, but when it comes to their own women, they don’t allow them any such rights,” he says.

In the past, politicians and religious leaders have made verbal agreements at jirgas that women will not be allowed to vote. Sometimes, announcements were made in mosques about a ban on voting for women.

A small number of women did vote in Timargarah and Chakdara towns of Lower Dir during the recent local elections. Civil rights activists termed as the “worst form of tokenism”.

Tahir Ali is an Islamabad-based journalist

Twitter: @tahirafghan